Tax-free profits

Welcome to the geography of tax avoidance

International investment flows are often concentrated in countries with relatively small economies. Why? Welcome to the world of tax avoidance.

Mailbox companies. We have all heard of them and know they are used by large corporations to avoid paying taxes. This website tells the story of just how much money is involved, which countries this money flows through, and who pays the bill.

Which countries are involved?

The graph below shows the amount of foreign direct investments (FDI) in 10 countries around the world (1). FDI is investment made by a company or entity based in one country, into a company or entity based in another country. One would imagine that these investments correspond to the size of a country’s economy, and expect the United States or China to lead global investment tables.

However, global FDI statistics show that these investments are concentrated in particular countries with relatively small economies, such as The Netherlands or Luxembourg (indicated in red). Indeed, the Netherlands is by far the largest exporter of FDI in the world, ahead of the United States and China.

Top 10 largest global foreign investors

https://datawrapper.dwcdn.net/axRWH/8/(opens in new window)

data [.xlsx](opens in new window)

This may seem strange, but the reason these countries rank so high is that large parts of the investments attributed to the Netherlands and Luxembourg (and other small economies with large foreign investment stocks) are in fact made by corporations and investors residing in other countries. They concern global investment flows that are passed through what are known as SPEs (2), also called mailbox companies. This means, for instance, that when a Dutch mailbox company invests abroad, this investment does not originate from a genuine Dutch business with material operations in the Netherlands.

Why use mailbox companies?

Many research reports in recent years have shown how the use of mailboxes in conduit economies enables large corporations to shift profits and avoid paying taxes in those countries where their actual economic activities take place (3).

The size of the mailbox company sector in a given country is an indication of whether that country is being used as a tax conduit or a tax haven. Consequently, when a country receives most of its foreign investments from mailbox companies abroad, it is certain to lose out millions of tax revenues each year. There are other motivations for using mailbox companies, such as obscuring ownership relations, money laundering, or making use of investor rights provided to corporations under a bilateral investment treaty network. These are not explored in detail here.

How much money is involved?

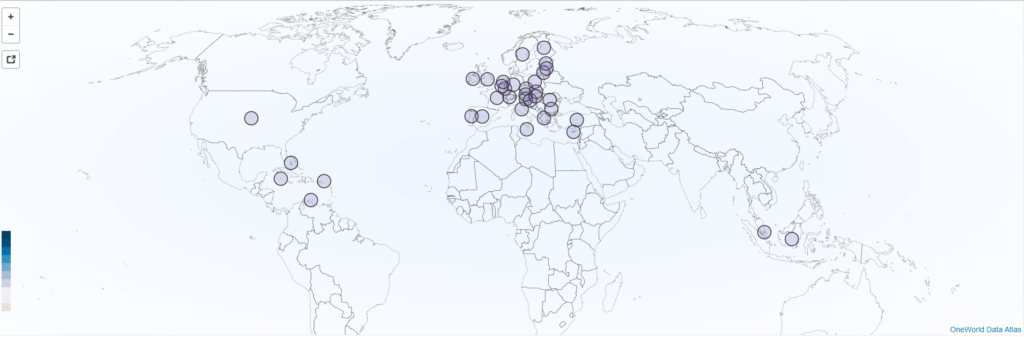

In some countries, the difference between money invested in the real economy and in mailbox companies is extremely high. These differences are visualised in the map below. It provides a breakdown between genuine investments and investments through mailboxes.

A breakdown of these difference between genuine and mailbox investments at bilateral level is currently only possible for countries that register foreign direct investment statistics separately for mailbox companies and genuine businesses. Only four countries (4) currently do so: The Netherlands, Luxembourg, Austria and Hungary (5).

Estimates on the mailbox company sector, however, can also be made for Ireland, the United Kingdom and Switzerland. For the methods used to calculate these numbers, please refer to the underlying methodology.

Incoming investments

The map below shows the size of incoming investments in a country, with a choice to include or exclude mailbox company-related investment from the figures. Toggle the ‘with mailbox’ and ‘without mailbox’ slider on the bottom of the map to see the difference. You can zoom in by double clicking. Click on the icon with the arrow to see the map full screen.

https://dataworld.s3.amazonaws.com/280c5498-1f10-4af9-9cb7-5cd30f47269f.html(opens in new window)

data [.xlsx](opens in new window)

Who are the largest investors?

The map above provides you with an idea of the sheer size of investment related to mailbox companies into the Netherlands, Luxembourg, Austria, Hungary, Ireland, Switzerland and the United Kingdom.

The use of conduit countries can only be understood by looking at the tax and investment benefits these countries offer to corporations, and the low barriers they set to establishing mailbox companies. A recent overview on tax benefits granted to corporations in European countries is provided in Eurodad’s Capital Flight Report 2015(opens in new window) .

The bar chart below shows that in most cases, conduit countries like The Netherlands and Luxembourg are among the top 10 investors in most European but also non-European countries.

Top 10 investors in the country

Click on the dropdown menu and move up and down with arrows + enter to look at each country.

https://datawrapper.dwcdn.net/jLYGg/12/(opens in new window)

data [.xlsx](opens in new window)

Where does the money go?

Routing investments through a mailbox that is based in a country offering tax advantages, such as the Netherlands, allows multinational companies to avoid taxes in multiple ways.

For instance, companies can set up a mailbox subsidiary that owns the company’s intellectual property rights in the Netherlands. This mailbox company then collects royalties from all subsidiaries in operating countries, e.g. for their use of a logo or a technology.

Such royalties lower the profits of these subsidiaries, leading to lower corporate income tax payments in the countries in which they operate. The Dutch mailbox can then transfer this income untaxed to tax havens such as Bermuda or reinvest it back into the global business.

In other words: the actual research and production of the intellectual property was done in another country, but a mailbox company in a country with favourable tax treatment for royalty payments can distribute that royalty income tax free.

Outgoing investments

The map below shows the magnitude of outgoing investments held by one country in another. The size of investments channeled through mailbox companies is shown in a popup after clicking on the receiving country. Click on the map to go to the animated map.

(opens in new window)

(opens in new window)

data [.xlsx](opens in new window)

Who pays the bill?

The European Commission estimates the annual loss of tax revenue through tax fraud, tax evasion and tax avoidance to be € 1,000 billion per year. This is more than the combined annual spending on health care in Europe. € 150 billion of this so-called ‘tax gap’ is generated by tax avoidance.

The impact of tax avoidance on the wider economy is far reaching and has been growing in the last two decades. There are at least two immediate consequences.

First, while large corporations are able to avoid paying taxes, small and medium-sized companies and salaried workers are left to pay the tax bill. This feeds inequality. Shareholders benefit whilst workers and smaller companies pay the bill. It also leads to unfair competition: with a lower tax bill, large corporations have lower costs than smaller and medium-sized companies.

Second, increased tax avoidance by multinational corporations has stimulated a race to the bottom in terms of taxation. More and more countries try to establish a domestic tax avoidance industry and offer a favourable tax regime. This increasingly includes tax incentives, such as patent boxes. The competition between states has also empowered multinational corporations: they can play off countries against each other by threatening to relocate. Moreover, multinationals can opt out of national investment and tax laws, by engaging in regime shopping.

What should be done?

1. Increase fiscal transparency

More transparency is needed for citizens, journalists, NGOs and others to assess the impact of governments’ tax policies. Transparency also contributes to the accountability of governments. Investors and consumers will benefit from public access to information as well.

We ask for:

- Mandatory and public country-by-country reporting for all multinational corporations. Corporations should report financial data for each country in which they operate, including profit/loss, turnover, number of employees, and corporate income taxes.

- All tax rulings (agreements between tax authorities and individual companies) should be made public.

2. Stop the harmful race to the bottom

Creating more tax incentives and loopholes in the context of ‘tax competition’ only maintains a system that benefits the private sector, but causes major public losses. Governments should instead prioritise joint efforts to tackle tax avoidance and evasion.

We ask for:

- The implementation of a common tax base in the EU (under the Common Consolidated Corporate Tax Base);

- The creation of a minimum corporate income tax rate;

- Effective taxation within the EU, by adapting existing rules in the European Union regarding taxation, such as the Interest and Royalty Directive.

This is a project of:

Supported by:

Notes

(1) Not all countries in the world were included in this research for reasons of scope and data availability. Only four countries register foreign direct investment flows separately for mailbox companies and genuine businesses, namely, the Netherlands, Luxembourg, Austria and Hungary. Counterpart economies for this FDI were restricted to European countries, tax havens, Turkey and Indonesia. The latter two were chosen to provide a comparison with non-EU counterparts. With regard to the definition of FDI, if the cross-border investment is below 10 per cent of the equity, the investment is considered a portfolio investment and refers to transactions on the stock market.

(2) SPE or Special Purpose Entity is a general term to describe “entities with no or few employees, little or no physical presence in the host economy, whose assets and liabilities represent investments in or from other countries, and whose core business consists of group financing or holding activities.”(OECD 2013). Large corporations use them to attain a domicile in a particular country; this, in order to exploit specific legal loopholes and/or regulations. This practice gives a distorted view of the underlying capital flows.

(3) For more examples of tax avoidance, please explore other SOMO research on tax avoidance.

(4) In order to understand why it is that these particular countries are used, we invite you to read our research that explores the use of SPEs by corporations in detail.

(5) Then again, the information quality for Hungary is poor and does not give a good representation of the SPE sector in this country.

Partners

-

Oneworld

Related news

-

The Netherlands – still a tax haven Published on:

Arnold MerkiesPosted in category:Publication

Arnold MerkiesPosted in category:Publication Arnold Merkies

Arnold Merkies

-

Tax avoidance in Mozambique’s extractive industriesPosted in category:Long read

Tax avoidance in Mozambique’s extractive industriesPosted in category:Long read Vincent KiezebrinkPublished on:

Vincent KiezebrinkPublished on: -

The treaty trap: The miners Published on:

Vincent KiezebrinkPosted in category:Publication

Vincent KiezebrinkPosted in category:Publication Vincent Kiezebrink

Vincent Kiezebrink