Tax avoidance or state aid?

How the Dutch tax authority gave Shell’s foreign shareholders a gift of more than 7 billion euros.

If the recent upheaval about the dividend tax in the Netherlands has taught us anything, it’s that Royal Dutch Shell and Unilever shareholders are not keen on paying Dutch dividend tax. The Dutch government recently released twelve memos concerning the dividend tax which were authored by civil servants at the Dutch Ministry of Finance and the Ministry of Economic Affairs which extensively mention the position of both companies and their interests in the debate over whether to abolish the dividend tax. Much has already been said about Unilever, but until now less attention has been paid to Shell’s interests in this debate. In the text below you can read about how Shell has enabled about half of its shareholders to avoid paying dividend tax for the last 13 years – with approval from the Dutch Tax and Customs Administration – and how much this has cost the Dutch treasury.

The background

In 2004, Shell found itself in a difficult situation. The company was listed as two separate corporations on the stock exchanges in the United Kingdom and the Netherlands and was hoping to merge the two companies. As the largest group of shareholders held Dutch shares at the time, the company planned to locate its new headquarters in the Netherlands. However, this was complicated by the fact that the United Kingdom levies no taxes on dividends paid to shareholders, while the Netherlands does. Because of this fact, merging the two companies and locating their headquarters in the Netherlands would mean that holders of British shares would then have to pay Dutch dividend tax. This would not be a problem for Dutch shareholders, as well as many foreign shareholders, as it would cost them nothing extra. They would be able to offset this tax payment so that the net yield of the dividend would remain the same. But British shareholders would not be able to offset the dividend tax they paid. For them, Dutch Shell shares would thus become less profitable and less attractive.

For the merger to go through, Shell needed the approval of its British shareholders. So a tax avoidance structure was fabricated – in consultation with the Dutch tax authorities – through which Shell could circumvent the dividend tax for these shareholders.

Tax avoidance structure using Jersey

The structure works as follows: Dutch Shell shares are divided into two categories, A-shares and B-shares. Both have the same value and both earn the same annual rate of return in dividends. In 2017, 54 per cent of Shell’s shares were A-shares, while 46 per cent were B-shares. The main difference between the shares is that while dividends for the A-shares are simply paid out in the Netherlands (where 15 per cent dividend tax is owed), payment of the B-dividends is processed via a so-called ‘Dividend Access Mechanism’.

On 19 May 2005, Shell set up the ‘Royal Dutch Shell Group Dividend Access Trust’, registered on Channel Island Jersey. This trust holds a ‘Dividend Access Share’, giving it the right to all B-dividends paid by Shell. Instead of being paid out from the Netherlands, these dividends over Dutch B-shares are paid out from Shell’s British subsidiary The Shell Transport and Trading Company. As such, dividends on Dutch B-shares are disbursed to a Jersey trust via one of Shell’s British subsidiaries. In this way, the payment is not subject to Dutch dividend tax. After receiving the dividend, Shell’s Jersey trust is required to pay it onward to the actual holders of the B-shares. The fact that in this case the dividend is initially disbursed to the Jersey trust from the United Kingdom is exceptional, and raises the question of whether it complies with Dutch legislation. In an article(opens in new window) published June 16, the Dutch newspaper Trouw explains why disbursement of these Shell dividends from the United Kingdom is likely to be in violation of Article 1 of the Dutch Dividend Tax Act.

Via this construction, dividends paid out over the last 13 years have been made subject to the tax legislation of the United Kingdom and Jersey, instead of that of the Netherlands. And it just so happens that the United Kingdom and Jersey do not levy taxes on dividends.

Ruling by the Dutch Tax Authority

Shell operates under a ruling by the Dutch tax authority to carry out this tax avoidance construction. The ruling grants ‘certainty in advance’ to Shell, to make clear that all has been properly arranged. It was first granted in 2004 and was then renewed in 2015, with Shell’s acquisition of British Gas.

According to Shell, this tax structure was intended to be temporary, because at the time (around 2005) it was expected that the Dutch dividend tax would soon be eliminated. Shell based this on statements by former Dutch State Secretary of Finance, Joop Wijn (CDA political party): “The message to the corporate sector is that we don’t see this tax surviving for long.” In 2007, the dividend tax rate was reduced from 25 to 15 per cent, but a repeal never materialised. Nonetheless, roughly half of the company’s shareholders have paid no tax on dividends paid out by Shell over the last 13 years – due to this agreement between Shell and the Dutch tax authority.

Shell has helped shareholders to avoid more than €7 billion in dividend taxes

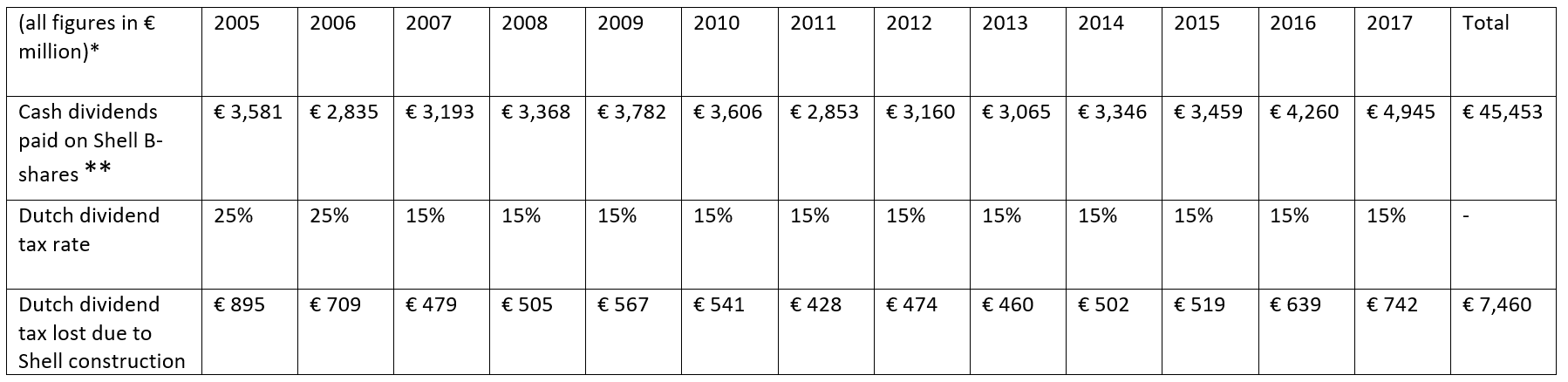

In contrast, the Netherlands has suffered a significant loss of income. Just how much has been lost in tax revenue can be estimated by multiplying the dividends paid out on Shell’s B-shares each year by the rate which was in effect for Dutch dividend tax in that year. In the 2010-2017 period, Shell paid its shareholders partly in cash and partly in shares. This research looks only at the yields that would have been gained from the dividend tax on the cash dividends disbursed. As shown in the table below, we estimate that this avoidance construction has cost the Netherlands approximately €7.5 billion in total.

* Royal Dutch Shell plc reports figures on paid dividends in USD in their annual reports. We used the exchange rate of 1 May 2018 to convert these figures to EUR: $1 = €0.83

** These figures originated from the corresponding Royal Dutch Shell plc annual reports, published on the company’s website(opens in new window) .

In its 2017 annual report, Shell reported that the company is no longer authorised to issue B-shares, according to the Dutch tax authority’s ruling. Apparently, this is a concession that the Dutch tax authority imposed at the time of Shell’s move to the Netherlands, in order to ensure that the company would not be able to offer exclusively B-shares to its shareholders in the future, which would have allowed them never to pay Dutch dividend tax again.

It is of course hypothetically possible that shareholders possessing B-shares live in the Netherlands, and thus pay Dutch income tax. That would completely negate any Dutch revenue lost through the dividend tax, as the dividend tax functions as a withholding tax, preceding income tax paid by residents of the Netherlands. The fact that Shell’s avoidance structure was created specifically for shareholders of the British branch of the company makes it likely that few Dutch shareholders hold B-shares. Shell previously reported that fewer than 5 per cent of all Shell’s shareholders are Dutch nationals, while a list of B-shareholders from the Thomson Reuters Eikon company database gives the impression that fewer than 1 per cent of those shareholders are Dutch nationals. Based on these figures, it can be concluded that the estimated amount of € 7.5 billion lost in tax revenue might be lowered by a maximum of 5 per cent, after deducting any dividend taxes which Dutch holders of B-shares would have to pay. In that case, the loss would amount to € 7.1 billion.

The consequence of Shell’s tax avoidance construction is that a considerable portion of B-shareholders are able to avoid paying dividend tax. Some Shell shareholders thus enjoy a tax advantage that is not easily available to shareholders of other Dutch companies. This amounts to preferential treatment by our own Dutch tax authority, likely intended to influence the move of the British stock exchange listing to the Netherlands.

Illegal state aid?

The question is whether the Dutch tax authority has acted in accordance with Dutch legislation and regulations on this matter. Furthermore, it is unclear whether the ruling is a violation of EU state aid rules, constituting a case of state aid to Shell – the type of support that caused the Netherlands to be investigated several times in the past by Margrethe Vestager, European Commissioner for Competition? If that is the case, the European Commission could require the Netherlands to recover the previously mentioned € 7.5 billion. These questions cannot be answered with certainty without knowing the specific content of the ruling; until now, however, that has been kept confidential.

Responses from Shell and the Dutch tax authority

In response to the findings in this document, Shell reacted only with the following statement:

“Our capital structure with A and B shares and the ‘Dividend Access Mechanism’ are in accordance with applicable fiscal laws and regulations in the Netherlands and the United Kingdom.”

The Dutch tax authority stated that rulings are always issued within legal parameters, but that the situation of individual taxpayers could not be addressed. The tax authority did state that dividends on Shell B-shares are paid by foreign companies, and that the Dutch tax authority, therefore, may not levy tax on these, in accordance with the Dividend Tax Act. In their response, however, the Dutch tax authority failed to acknowledge that this is a dividend on Dutch shares, which should therefore also be disbursed from the Netherlands.

Investigation into the rulings

In late 2017, Menno Snel, Dutch State Secretary of Finance, ordered an investigation into rulings with an international character, which reviewed the issuance procedure. Only 72 rulings were investigated in detail, and in five of these (approximately 7 per cent) “fiscal-technical content” was found that was likely incorrect. Furthermore, the Dutch tax authority recently ordered an investigation into the issue of whether there is sufficient transparency on rulings. That investigation concluded that publishing rulings is not a worthwhile objective, as it would provide no added value and only involve extra work. The study stated that it had been carried out by an independent commission, consisting of two external experts, two tax authority staff members and two Ministry of Finance staff members.

Their conclusions are in stark contrast with the various scandals surrounding rulings issued by the tax authority, such as the state aid case started by the European Commission regarding rulings for Starbucks and IKEA(opens in new window) , and the controversial ruling for Procter & Gamble, which was previously reported(opens in new window) on in the Dutch media. It would seem that the ruling granted to Shell by the Dutch tax authority will be next on this steadily growing list.

Transparency is needed to truly tackle tax avoidance

To make clear that this government truly intends to tackle tax avoidance, as has been repeatedly claimed in the most recent coalition agreement, full disclosure and transparency on ruling practices are needed – possibly by means of a parliamentary enquiry. Furthermore, the Dutch Ministry of Finance and the tax authority must shed light as quickly as possible on the legitimacy of this deal with Shell, which appears to have cost Dutch taxpayers € 7.5 billion so far. Only then can the stated intentions of this government to address tax avoidance be taken seriously, and can a start be made on clearing the Netherlands’ bad reputation as a tax haven.

Do you need more information?

-

Vincent Kiezebrink

Researcher

Related news

-

The Netherlands – still a tax haven Published on:

Arnold MerkiesPosted in category:Publication

Arnold MerkiesPosted in category:Publication Arnold Merkies

Arnold Merkies

-

Tax avoidance in Mozambique’s extractive industriesPosted in category:Long read

Tax avoidance in Mozambique’s extractive industriesPosted in category:Long read Vincent KiezebrinkPublished on:

Vincent KiezebrinkPublished on: -

The treaty trap: The miners Published on:

Vincent KiezebrinkPosted in category:Publication

Vincent KiezebrinkPosted in category:Publication Vincent Kiezebrink

Vincent Kiezebrink