Brazil nuts: Exploitative social and economic conditions in the Bolivian Amazon

Brazil nut trees are among the highest in the Amazon rain forest, reaching up to 50 metres. Production is not economically feasible outside their natural habitat, meaning that all of the Brazil nuts traded worldwide are collected in this pristine forest. Trade in this nut has therefore been called the cornerstone of Amazon conservation(opens in new window) as it allows local and indigenous communities to generate income whilst preserving the rainforest.

However, the working conditions during the Brazil nut harvest, and in the processing factories are often appalling. New research in Bolivia has exposed cases of workers having to work in order to pay off debts from the previous harvest, abusive conduct by employers, child labour, and wages too low to support workers and their families. Furthermore, whereas the companies that collect, process and export Brazil nuts have benefited from rising prices for the product, the wages of harvest workers have flatlined.

This longread focuses on the Brazil nut sector in Bolivia. It looks at working conditions both in the forest during harvest time and in the country’s processing factories. It also covers the international supply chain from tree to supermarket. For this research, SOMO joined forces with the Belgian solidarity organisation FOS(opens in new window) and the Bolivian Centre for Research and Promotion of Farmers (CIPCA(opens in new window) ). This goal of the research – to support Bolivian trade unions in price negotiations with processors – was successful: in November 2020, harvest and factory workers as well as indigenous and local forest land owners united for the first time to demand better prices and wages.

The harvest

During harvest periods, workers collect the fruit that has fallen from Brazil nut trees deep in forest. To access the nuts, they split open the woody outer shell of the fruit with a machete. At the end of the day, workers carry the harvested nuts on foot to the collection centres. Depending on the available infrastructure, the nuts are then transported by boat or truck to the processing factories, mostly located in the city of Riberalta.

Brazil nut harvest. CIPCA

Here, the nuts are sorted, dried, boiled, shelled, cleaned, selected and packed. When they arrive from the forest, the nuts are still encased in a hard shell. Workers in the processing factories remove these shells one by one with a simple tool. This is the most labour intensive phase of the processing; shelling has been mechanised in only a few factories.

Around 14,000 people work in the Bolivian Brazil nut harvest sector, and around 8,000 workers are involved in processing. Processing factories operate eight months per year, and the harvest itself takes about three months. The harvest workers interviewed for this article were all employed in barracas, the managerial and physical units for Brazil nut collection. If they also own the land concession, the owners of the barracas are called barraceros. Two thirds of the workers interviewed for our research were employed by barraceros.

Due to land reforms since 1996, the historic dominance of the barraceros in the Brazil nut industry has dwindled. Indigenous and peasant communities now own about 52 per cent of the productive land, and about 46 per cent of total Brazil nut exports originate from this. However, due to a lack of capacity, communities also hire workers and engage with contractors and private companies in order to supply the market.

Child labour

Support from family members is very common in the Brazil nut sector, and child labour is widespread. Seventy-one per cent of the interviewed workers bring their entire family to harvest, and 86 per cent of the processing workers interviewed have at least one family member helping them in the factory. Although workers did not specify the ages or the number of children helping them, they did provide details about who accompanied them to the workplace, and about the composition of their households. Based on these fact, an estimated 64 per cent of workers are accompanied by minors when they harvest, and roughly a third of them bring children below the age of 14 to work.

Two thirds of the harvest workers said that their children’s schooling schedules have been affected by this work. Forty per cent of harvest workers reported that their children had lost a year of education, and one tenth of them indicated that their children had missed two or more years of schooling.

It was not possible to properly estimate the number of factory workers who take minors to the workplace. Workers claim that children below the age of 14 have not been welcome in the factories for the past few years. However, minors over the age of 14 are allowed, provided they have authorisation from the Children’s Protection Authority. Since 2019, a number of factories have only been allowing helpers aged 18 years and older. Since over a third of the interviewed factory workers reported having children in the age group 14 to 17, the conclusion is that this group has the most significant risk of child labour.

Harvest workers, together with the family members that accompany them, make on average US$397 per month. Processing workers (and their helpers) take home about US$348. Whereas these wages are above the national minimum wage of US$297, they are often the total earnings of several family members. This means that the individual workers in a family unit earn less than the minimum wage. More importantly, these wages are not enough to support an entire family in Bolivia, as the minimum monthly income needed for a family to lead a decent life there is an estimated US$538-US$735.

The informality of employment in the Brazil nut sector is yet another problem. Two thirds of the harvest workers interviewed and three quarters of the factory workers reported that they did not have a written contract. This makes it more difficult for workers to claim their rights.

Forced labour?

Based on the information collected during the interviews, the conditions for Brazil nut workers cannot technically be considered as forced labour(opens in new window) . For many workers, however, it feels that way. Among the harvest and factory workers, respectively 12 per cent and 28 per cent described their employment situation as such. A number of practices described in their accounts also strongly indicate forced labour situations(opens in new window) .

For instance, it is common for harvest workers to take out loans in the form of advance payments (88% of them stated that they do so). This so-called habilito makes it more difficult for workers to quit their jobs should they want to, and is clearly a form of bonded labour. In more extreme cases, workers reported having to do harvest work in order to pay off last season’s debts with their employers.

Moreover, in the often remote and isolated collection camps (barracas), employers also take advantage of their monopoly position on groceries and supplies by selling in cash or credit to workers at prices well above market rates. Other reported indicators of forced labour or abusive working conditions include physical aggression (reported by 9% of harvest workers and 6% of factory workers), sexual harassment (12% and 17%), threats (18% and 36%) and the withholding of payments and personal belongings (15% and 11%).

The market

Worldwide, 27,500 tonnes of Brazil nuts are consumed each year(opens in new window) . This amount is very modest when compared to the sales of most other tree nuts, such as almonds (1,171,268 tonnes), walnuts (795,843 tonnes) and cashews (706,979 tonnes). Just three countries are responsible for the total global production(opens in new window) : Bolivia (78%), Peru (16%) and Brazil (6%). In retail, raw Brazil nuts are sold in packs, in dried fruit and nut mixtures, and in breakfast products. Food and personal care companies also process the nuts to use as an ingredient in various snacks, baked goods, confectionery and cosmetics.

Bolivia is categorised as a lower middle income country by the World Bank(opens in new window) . Trade(opens in new window) from Bolivia is dominated by natural gas (32%), zinc (17%) and gold exports (12%). However, the export of Brazil nuts is also important. With 2 per cent of total exports (25,000 tonnes and US$ 205 million in 2018), Brazil nuts are Bolivia’s second most important agricultural export product behind soy (8%). And in the north of the country, the Brazil nut sector is ” target=”_blank” rel=”noreferrer noopener”>the most important economic activity.

The value distribution

The structure of the international supply chain for Brazil nuts is relatively simple. In the producing countries, the nuts are harvested, processed and exported in bulk. In the importing countries, the nuts are sold wholesale by trading companies to food companies that in turn package them for retail companies, or directly to when the traders own packaging facilities. Ultimately, the raw Brazil nuts in supermarkets of importing countries are the same as those that leave the processing factory in Bolivia. However, the latter cost about 2.5 times more.

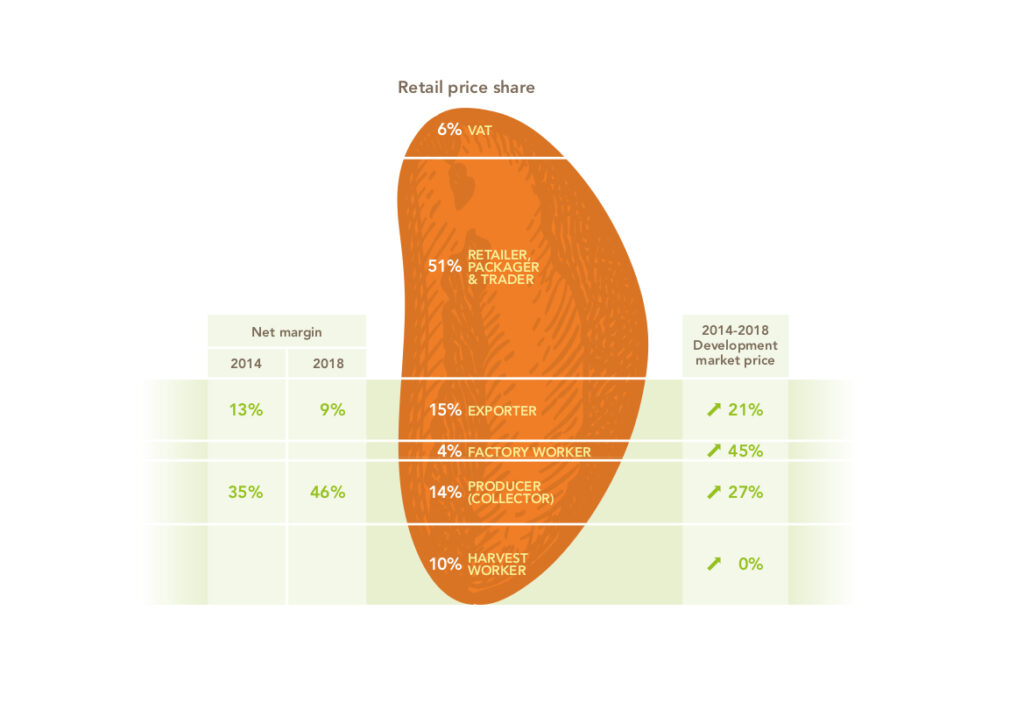

International traders, packagers (processors) and retailers based in consuming markets account for roughly half of the value (gross margin) in the supply chain of this commodity (see Figure ). Only a minor share (14%) of the retail price ends up in the pockets of Bolivian harvest and processing workers.

This is particularly low(opens in new window) , since low-skilled workers generally receive 23 per cent of the consumer price in global food supply chains. Yet the discrepancy can be even more extreme; research commissioned by shows that the combined smallholder producer and worker share of the consumer price for products like avocados, bananas and green beans is as low as 7 per cent.

Figure : Brazil nut supply chain actor’s gross share of the retail price (2018)

Source: SOMO, based on research by Poveda Avila and the Belgium composite retail price(opens in new window) of US$19.16 per kilo.

Between 2014 and 2018, the price received by harvest workers per box of Brazil nuts flatlined. However, during this same period, prices for all other actors in the Bolivian Brazil nut supply chain improved.The net margins for processing factories (exporters) and producers (collectors) were an estimated 9 and 46 per cent in 2018, compared to 13 and 35 percent in 2014. However, despite these improved margins and prices, the processing industry insisted for many years that market conditions did not allow for higher wages for harvest workers.

The industry perspective

In the last two decades, have documented abusive practices, the most recent of which was published in 2013. However, the research for this article was the most in-depth and comprehensive study of socioeconomic issues in the Brazil nut supply chain in many years.

International frameworks for responsible business conduct(opens in new window) expect that companies linked to risks of human rights violations identify and address such risks appropriately, among other actions. Since the working conditions in the Bolivian Brazil nut sector are so problematic and persistent, the logical next step in the research was to identify the companies linked to these risks and to explore how they address them. To this end, we contacted companies along the supply chain for their reactions to the research findings (see box below).

In Bolivia, the two industry organisations for producers (collectors) declined to react to the research findings. Both Urkupiña, the country’s leading exporter, and Cadexnor, the industry organisation for exporters, responded with general discontent. They mainly voiced unsubstantiated accusations of research bias and expressed concern about the potential economic harm that the publication of this research could mean for the sector. Export company Tahuamanu responded with a number of specific remarks.

Companies and industry organisations along the Brazil nut supply chain

Producers

- ASPROGOAL (Association of Rubber and Almond Producers).

- AARENAMAPA (Agroindustrial Association of Natural Resources of the Manuripi River in Pando).

Exporters

- CADEXNOR (Chamber of Exporters of the North), the industry association of exporters.

- Urkupiña, Bolivia’s largest exporter of Brazil nuts. A third of the country’s Brazil nut exports are traded by this company. Voicevale, August Töpfer and Lidl are among its clients.

- Tahuamanu, the second largest exporter of Brazil nuts in recent years. Nine per cent of Bolivia’s Brazil nut exports are traded by this company.

Traders

- Voicevale, the leading international trader of Brazil nuts . The company is headquartered in London, UK but has offices in a number of other countries around the world. In the period between 2014 and 2018, the multinational’s share of the Brazil nuts imported from Bolivia to the EU reached 28 per cent. Voicevale is involved in wholesale trade.

- August Töpfer, the third leading EU importer of Brazil nuts from Bolivia, is based in Hamburg, Germany. August Töpfer is a wholesale company that mostly packages Brazil nuts for its European retail clients.

Packagers

- PepsiCo, a leading US-based multinational snack and beverage company. PepsiCo products with Brazil nuts include granola (Quaker) and snacks (Duyvis and Nut Harvest).

Retail

- Lidl, part of the German-based Schwarz Gruppe, the EU’s leading retail group. Lidl is also the ninth most important EU importer of Brazil nuts from Bolivia. One of the company’s products is a retail package of raw Brazil nuts under their private label Alesto.

- Aldi, headquartered in Germany, is another leading retail group in the EU. The supermarket’s catalogue includes packaged Brazil nuts with the Nature’s Gift brand.

Industry response

Downstream the international Brazil nut supply chain, the leading global trader Voicevale did not comment on the exploitative working conditions identified in this research. Packaging and importing company August Töpfer stated in an email to SOMO that it did not recognise many of the research findings, and that these findings were not representative of its supplier, Urkupiña. While the company did not specify which findings were supposedly incorrect, it underlined that it was taking the report’s ‘concerns’ seriously and that it intended to take them up with Urkupiña.

Multinational food company PepsiCo emphasised that it only sources very limited volumes of Brazil nuts compared to supermarkets, but that it would investigate the issues raised in the research with its suppliers and that to this end had started a desktop review of its suppliers’ policies and practices.

In its elaborate reaction, retail company Aldi reported that a company human rights risk assessment in the nut sector had independently identified those in Brazil nut production as salient. As follow up, the retailer has started a dedicated human rights impact assessment of the Brazil nut supply chain to investigate the possible risks in depth and to develop a course of action for mitigation. While their project could not be concluded due to the pandemic, Aldi expressed its commitment to do so through joint action with its business partners. The company also stated that the findings of this research would support their interventions.

Lidl mainly provided us with more detail about its generic policies for ethical sourcing. However, this leading supermarket group also emphasised that it was taking the study very seriously and would use it as an opportunity to sensitise its business partners and call for a review of their policies and practices.

Discussion

The research presented in this article does not identify specific employers or suppliers that are engaged in abusive conduct in Bolivia. However, based on 70 interviews with workers and confirmation by trade union leaders representing both harvest and factory workers, the problems raised in the interviews are considered representative of the problems generally affecting workers in this industry. The industry’s responses to the issues raised are diverse. However, it is clear that the their understanding about the working conditions in Bolivian Brazil nut harvesting and processing is often incongruent with the conclusions reached in this research.

This is alarming, as awareness about problematic working conditions is a pivotal step towards addressing them. However, the contacted downstream companies are investigating the problems raised and are taking them up with their suppliers. Moreover, Aldi, one of the most influential retailers in the industry, has also committed to addressing the problematic working conditions once its investigation has been completed.

While this article presents an analysis of the uneven distribution of value in the supply chain, only trader Voicevale reacted specifically to this issue by emphasising its minor share of the retail price. This silence from the industry is more worrying than the companies’ reactions to exploitative working conditions. Indeed, compared to some of the other international food commodity supply chains for which more details are available, the share of the retail price that is pocketed by Brazil nut harvesters is not particularly low. Nonetheless, the box rate for harvesters is considered insufficient, and does not allow them to adequately support their families. Moreover, the box price for harvested Brazil nuts has not improved over the past decade, despite improved market conditions.

This research contributed to the formation and empowerment of a historically broad alliance(opens in new window) of harvest and factory workers, indigenous and local land owners and cooperatives demanding better prices and wages. However, in the agreement they reached with the industry end of December 2020, prices and wages are even lower than those in 2018 and 2019. While the current pandemic may indeed lead to lower and more unstable market prices as is claimed by the industry in the negotiations, lower prices and wages in production are likely to aggravate the problematic conditions this research has exposed. Now more than ever, industry stakeholders all along the supply chain need to take responsibility for improving wages and working conditions in the harvesting and processing of Brazil nuts.

SOMO, FOS and CIPCA commissioned this research in order to support the trade unions there in their price negotiations with processors. The central focus of the research (conducted between June 2018 and June 2020) was the distribution of value along the supply chain, and working conditions connected with the harvesting and processing of the nuts. Part of the research was a random survey that was administered to 34 harvest workers and 36 factory workers. In the interviews conducted in January 2020, respondents were asked about their working and living conditions. The research report authored by Pablo Poveda Avila will be published by CIPCA this year.

Do you need more information?

-

Sanne van der Wal

Senior Researcher

Partners

-

FOS

-

CIPCA – Centro de Investigaciu00f3n y Promociu00f3n del Campesinado

Related news

-

Modern slavery is still lurking in your coffee cupPosted in category:News

Modern slavery is still lurking in your coffee cupPosted in category:News Joseph Wilde-RamsingPublished on:

Joseph Wilde-RamsingPublished on: -

Bitter brew Published on:Posted in category:Publication

-