Caught on camera: How CCTV tech contributes to human rights abuse in Iran

European technology companies and investors that fail to do risk-based downstream due diligence risk contributing to severe human rights violations committed by repressive regimes, such as in Iran

Key takeaways for policymakers:

- Closed-circuit television (CCTV) surveillance is widespread across the globe, and in states with weak rule of law and lack of good governance such as Iran, it is used to perpetrate severe human rights abuses. If European companies manufacturing and selling CCTV surveillance technology – and their investors – fail to conduct risk-based downstream value chain due diligence, such technology can easily end up in the hands of bad actors and contributing to severe human rights abuses.

- “Risk-based downstream due diligence” is a practical concept that is already an expectation of business under authoritative standards such as the OECD Guidelines and UN Guiding Principles by which companies and investors seek to prevent severe human rights abuses that could be committed with or using their products or services. Many companies and investors already conduct risk-based due diligence throughout their entire value chain, both upstream and downstream. Unfortunately, many other companies still do not.

- European lawmakers must recognise the importance of risk-based downstream due diligence to prevent surveillance technologies from contributing to harm and make risk-based downstream due diligence mandatory.

- By making the normative expectations for risk-based downstream value chain due diligence that already exist in international standards mandatory, European lawmakers in Brussels and European capitals can take a major step towards persuading companies and investors not to prop up repressive and undemocratic regimes and to instead move to prevent and avoid human rights abuses in their value chains around the world.

CCTV surveillance technology used to oppress human rights proponents and commit severe human rights abuses in Iran

As lawmakers in Brussels debate whether or not the EU Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD) should compel European companies to do just that, the repressive Iranian regime is providing a dramatic and devastating demonstration of why risk-based downstream due diligence is so essential.

CCTV technology – some of which is manufactured, marketed, and/or financially-backed by European companies and investors – is used as a tool by the Iranian government not only to intimidate and prevent protesters from exercising their basic rights, but also to identify individuals for apprehension, torture, and execution(opens in new window) . During the recent protests in Iran over the death of a young woman who had been detained by the Iranian “Morality Police” for “improperly” wearing her hijab, at least 20 protesters, including other women “improperly” wearing their hijab, have been placed on death row after being identified using various types of public (e.g. traffic) and private CCTV surveillance technology(opens in new window) . United Nations experts have decried the arbitrary and extrajudicial detention of these protesters, four of whom have already been executed(opens in new window) . Indeed, this is the reason that several CCTV manufacturers such as Hikvision(opens in new window) , Tiandy(opens in new window) , and Radis Vira Tejarat(opens in new window) have recently been sanctioned by the United States and European Union. Some of these CCTV manufacturers have business relationships with European companies(opens in new window) and investors(opens in new window) .

The recent use of CCTV surveillance technology to identify and persecute political opponents is only the latest example in a pattern of abuse by the Iranian government. From November 2017 to January 2018, nationwide demonstrations occurred in Iran against the government. Initially, the demonstrations mainly focused on the government’s failure to revive the Iranian economy, as well as high unemployment and inflation(opens in new window) . As the protests continued, demonstrators increasingly criticised alleged corruption in the government and among many of Iran’s leading political figures, including the Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei. The demonstrations were met with a brutal crackdown by government security forces against the protestors. Iranian judicial officials estimated that 1,000 people were arrested, whereas an unofficial source reported that at least 3,700 people were detained. At least one detainee in Tehran and two in other provinces died in custody under unexplained circumstances(opens in new window) .

One of those arrested was Leila Hosseinzadeh, then secretary of the Students’ Central Council of the University of Tehran. She was detained following Tehran’s police issuing a public call to identify students involved in the demonstrations, by releasing photos of protestors taken by CCTV cameras that the government claimed were “just” traffic control cameras(opens in new window) in front of the main entrance to the University of Tehran. She was subsequently sentenced to 30 months’ imprisonment on the charge of “association and collusion against national security” and an additional 12 months’ imprisonment for “propaganda against the state(opens in new window) ”.

This is just one example of the many documented cases of the Iranian government using CCTV surveillance to identify protestors. Nationwide protests in November 2019 about the abrupt rise in the price of fuel resulted in protestors switching off their cars in the middle of highways, streets and roads(opens in new window) . According to the UN Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in Iran, excessive and lethal force used by security forces repressing the demonstrations caused the deaths of over 300 people(opens in new window) . Significantly, the authorities used footage from CCTV traffic and security cameras and videos from social media platforms to identify and arrest protestors(opens in new window) . Police and security forces also publicly released footage of protesters, some taken by CCTV cameras throughout cities and towns,

Using such methods, Iranian authorities continued to carry out a vicious crackdown in the aftermath of the protests, arresting thousands of people(opens in new window) . In a cabinet meeting that was broadcast on the state’s television network, former President of Iran Hassan Rouhani said(opens in new window) :

“[F]ortunately, we have enough surveillance and monitoring systems and CCTV cameras to identify cars, their registration numbers and their drivers who have blocked roads and I ask the Judiciary to implement laws on this matter. I mean if someone disturbs people’s lives, causes insecurity and road blockage … it won’t be tolerable in this country”.

In our December 2022 publication Setting the Record Straight , SOMO and partners showed that the world’s leading normative standards for responsible business conduct, the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises and the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights, already expect companies to take account of risks associated human rights abuses that are perpetrated with their products and services, in other words, “downstream” in the value chain. This paper discusses and demonstrates the importance of downstream value chain responsibility of private companies manufacturing and supplying digital surveillance and monitoring technologies to authoritarian governments that are known to violate the rights to privacy, freedom of assembly and association, and freedom of opinion and expression. This paper focuses on the use of CCTV surveillance by government authorities, which has proliferated in today’s digital age. Companies that manufacture and/or supply CCTV cameras that are used by governments to commit human rights violations may themselves be contributing to those violations and have a responsibility to conduct risk-based downstream value chain due diligence to seek to prevent them.

Mass CCTV surveillance across the globe

CCTV surveillance and authoritarian are of course not limited to Iran – both can be found across the globe. According to the UN, data-intensive technologies threaten to create an intrusive digital environment in which both governments and companies are able to conduct surveillance, analyse, predict and even manipulate people’s behaviour to an unprecedented degree(opens in new window) . The UN, OECD, and EU are responding to this threat: the UN’s B-Tech Project aims to provide guidance on the application of the UNGPs to the technology space; the OECD’s Going Digital Project recently released a report on digitalisation in the context of responsible business conduct; and the EU has also published ethics guidelines(opens in new window) for trustworthy AI.

Chinese cities have the most CCTV cameras of anywhere in the world, with 18 out of the top 20 most surveilled cities(opens in new window) being in China. Urumqi, capital of Xinjiang province, is currently the 13th most surveilled city in the world. Xinjiang is now synonymous with systematic and massive human rights violations committed against Muslim Uyghurs and other ethnic minorities native to the province. In combination with facial recognition and other tracking technologies, the Xinjiang government uses mass CCTV surveillance to identify and monitor Uyghurs, leading to egregious human rights abuses, including ethno-religious discrimination, as well as arbitrary detention and forced labour in mass internment camps or so-called ‘political education centres’ for

Mass surveillance may also have a ‘chilling effect’ on the rights to freedom of expression and assembly, disproportionately affecting journalists, human rights defenders and

.

The responsibility of CCTV camera manufacturers to conduct risk-based downstream due diligence to avoid contributing to human rights abuses

Normative expectations for responsible business conduct

Companies – including those that manufacture and/or supply CCTV technology and equipment – have responsibilities under the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (UNGPs) and/or OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises (OECD Guidelines) to respect human rights and conduct due diligence across the entire value chain of the products and services they provide to avoid contributing to human rights abuses. This responsibility applies to all companies, regardless of their size, sector, operational context, governance structure or location of their operations, and all internationally recognised human rights.

Meeting this responsibility requires companies to avoid causing or contributing to adverse impacts through their own activities, and to seek to prevent or mitigate adverse human rights impacts directly linked to their operations, products or services by their business relationships (even if they have not contributed to those impacts). For example, companies manufacturing CCTV cameras that are used by government authorities to identify and prosecute peaceful protestors may be directly linked or even contributing to that government’s violations of the freedom of assembly and association.

Companies should implement their responsibility to respect human rights by carrying out risk-based human rights due diligence both upstream and downstream in the value chain. Companies can proactively manage potential and actual human rights impacts with which they are involved through human rights due diligence. Due diligence, as defined in the OECD Guidelines, is a six-step process according to which companies are expected: (1) to embed RBC into their policies and management systems; (2) to identify actual or potential adverse impacts on RBC issues; (3) to cease, prevent or mitigate those impacts; (4) to track the implementation and results of due diligence; (5) to communicate how identified impacts are addressed; and (6) to provide for or cooperate in remediation when appropriate. The UN has recommended that companies selling surveillance technology perform, as part of their HRDD, a thorough human rights impact assessment prior to any potential transaction. Meaningful engagement with rights-holders and stakeholders is both especially important and especially difficult, if not impossible, in the context of repressive regimes. Meaningful stakeholder engagement is necessary for accurate human rights impact assessments and thus the implementation of effective safeguards for the use of technology. Contractual agreements between these companies and states should contain strong human rights safeguards that prevent arbitrary or unlawful use of the technology and periodic reviews of the use of technology by states(opens in new window) .

Risk-based downstream HRDD is especially important for companies that have operations, products or services in high-risk contexts (including areas with rule of law issues and documented human rights violations). As HRDD is risk-based, the measures that a company takes to conduct HRDD should be proportionate to the severity and likelihood of the adverse impact. When the severity of the impact is high, the due diligence steps taken should be more extensive. In the context of mass CCTV surveillance by repressive regimes – often resulting in violations of the right to privacy, the right to freedom of assembly and association, and the right to freedom of opinion and expression, as well as violations of other human rights, including to not be discriminated against and the prohibition on arbitrary arrest or detention – companies manufacturing and/or supplying CCTV technology or equipment should conduct extensive risk-based downstream HRDD to ensure that they identify, prevent, mitigate and account for how these impacts are addressed. If adverse human rights impacts cannot be mitigated or prevented, companies may need to consider a moratorium on designing, developing, deploying, and/or selling

Complaints against companies to OECD National Contact Points

Importantly, companies headquartered or operating in an OECD member state or a non-OECD adhering state (46 countries in total) that allegedly fail to meet their responsibilities under the OECD Guidelines(opens in new window) may be the subject of a complaint to a National Contact Point (NCP). NCPs have a broad scope to handle complaints against companies headquartered as well as operating in OECD member- or adhering-

Several NCP complaints have been filed against surveillance companies for their involvement in alleged human rights abuses. For example, in June 2020 the Society for Threatened Peoples Switzerland (STP) filed a complaint(opens in new window) against UBS at the Swiss NCP concerning the bank’s financial ties with Hikvision, a provider of surveillance technology that has played a significant role in the mass surveillance of Uyghurs and other minorities in Xinjiang. The complaint refers to the “all-pervasive” modern surveillance technologies employed by the Chinese government, resulting in “cameras at every street corner” and “every entrance to public buildings [being] monitored”. The complainant alleges that CCTV surveillance, in combination with other surveillance and tracking technologies, has “greatly contributed to the growing oppression of the local Turkic communities, whose every step and activity is tracked and minutely observed”. STP argues that UBS has neither fulfilled its duties regarding HRDD nor sought ways to prevent or mitigate the adverse human rights impacts, despite being linked to those impacts through its financial ties with Hikvision.

EU governments must make risk-based downstream due diligence mandatory

It is clear that surveillance technologies – including CCTV – can be used to commit human rights violations “downstream” in the value chain of those products and services. It is also clear that all companies that manufacture and/or supply CCTV technology have a responsibility to respect human rights under the UNGPs and/or OECD Guidelines. Meeting this responsibility requires that these companies conduct risk-based downstream human rights due diligence to prevent or address adverse human rights impacts that may result from the use of CCTV surveillance by governments. Doing so is especially important for tech companies engaging in business activities with repressive regimes, for which there is a heightened risk of human rights harms. Companies should responsibly disengage from (or not engage in the first place with) business relationships if, following due diligence, they determine that they cannot minimise or avoid human rights abuses by their

Responsible disengagement may be inevitable in the case of tech companies providing sensitive, dual-use technologies to repressive regimes, when there is no way for those companies to ensure that such technologies will not be used to perpetrate or facilitate human rights violations.

In addition to being a normative expectation under international standards like the OECD Guidelines and UNGPs, downstream human rights due diligence is an important measure to mitigate companies’ legal, financial and reputational risks, particularly given growing,

By making the normative expectations for risk-based downstream value chain due diligence that already exist in international standards such as the OECD Guidelines and UNGPs mandatory, European lawmakers in Brussels and European capitals can take a major step towards persuading companies not to prop up repressive and undemocratic regimes and to instead move to prevent and avoid human rights abuses in their value chains around the world.

Acknowledgements: The authors would like to thank Karen Kramer (Center for Human Rights in Iran) and Marlena Wisniak (European Center for Not-for-Profit Law). Though the authors benefitted greatly from the insights provided by these individuals, the content of this article remains the full responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily reflect the viewpoints of the individuals nor their organisations.

The authors can be reached by email for comments:

Omid Shams

Joseph Wilde-Ramsing

‘Caught on camera: How CCTV tech contributes to human rights abuse in Iran’ is the third in a series of four publications on due diligence and doing business with repressive regimes like Iran.

Do you need more information?

-

Joseph Wilde-Ramsing

Advocacy Director

Partners

-

Justice for Iran

Related content

-

Setting the record straight Published on:

Joseph Wilde-RamsingPosted in category:Publication

Joseph Wilde-RamsingPosted in category:Publication Joseph Wilde-Ramsing

Joseph Wilde-Ramsing

-

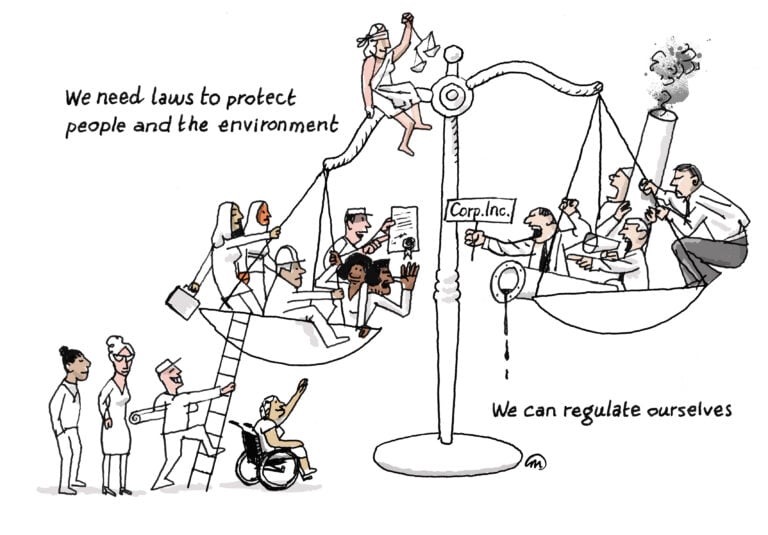

A piece, not a proxy Published on:

Joseph Wilde-RamsingPosted in category:Publication

Joseph Wilde-RamsingPosted in category:Publication Joseph Wilde-Ramsing

Joseph Wilde-Ramsing

-

Industry schemes must not be part of the EU Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence DirectivePosted in category:NewsPublished on:

Industry schemes must not be part of the EU Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence DirectivePosted in category:NewsPublished on: