Amazon finally sued for its illegal monopoly power

US lawsuit against shows flaws in how EU and UK deal with the tech giant

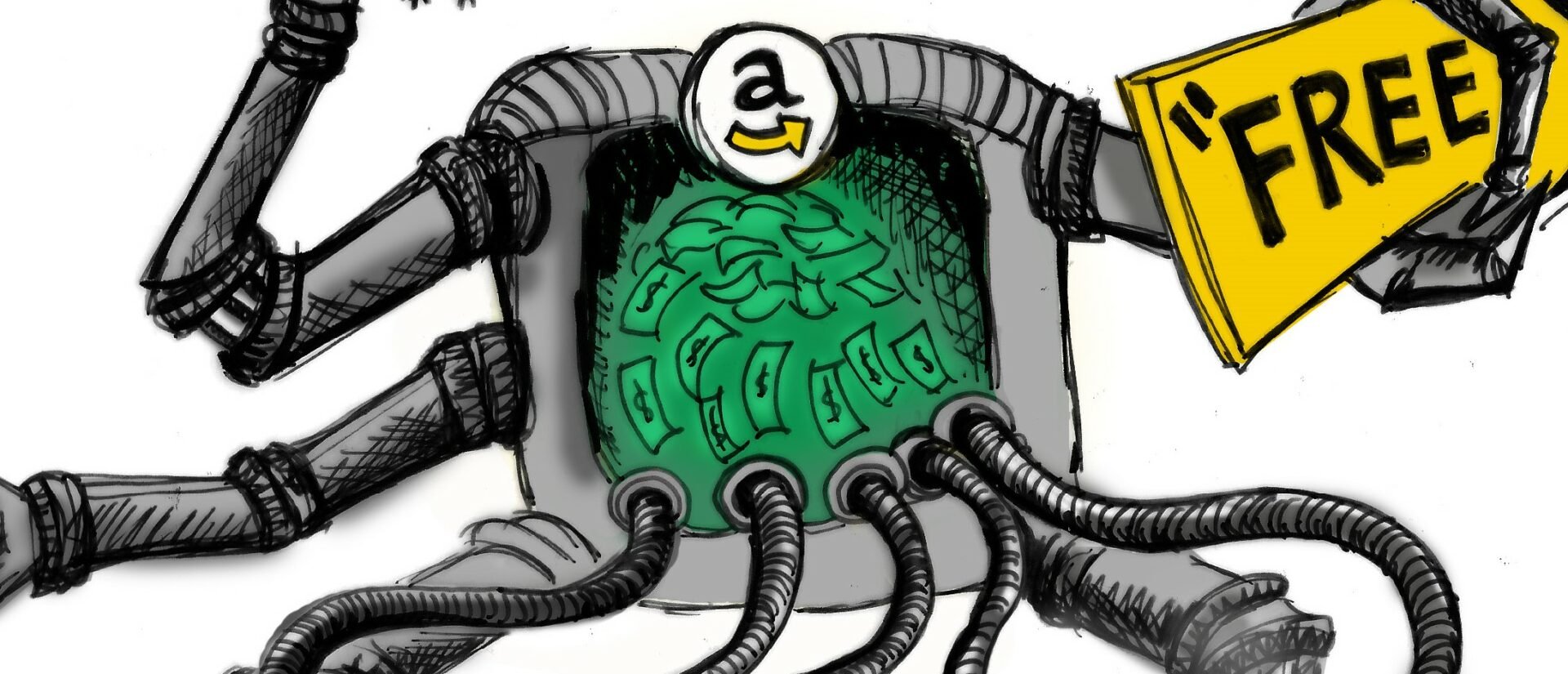

US regulators have finally sued Amazon for using illegal strategies to maintain its monopoly power. The long-awaited lawsuit(opens in new window) argues that Amazon’s monopolising strategies allowed the company to insulate itself from competition and extract monopoly rents, leading to higher prices generally. The case picks up on practices that EU and UK regulators had already investigated but it goes further, exposing that there is still much work to be done in Europe.

Monopoly lawsuit: United States Federal Trade Commission vs Amazon

“Amazon is a monopolist. It exploits its monopolies in ways that enrich Amazon but harm its customers: both the tens of millions of American households who regularly shop on Amazon’s online superstore and the hundreds of thousands of businesses who rely on Amazon to reach them”, the lawsuit states.

The suit, filed Tuesday, 26 September, by the United States Federal Trade Commission (FTC) and 17 US States, argues in the clearest possible terms that Amazon is a monopolist as it holds entrenched and durable monopoly power in the US. The regulators argue that the e-commerce giant has used illegal strategies to protect this power, among them:

- Preventing retailers from offering lower prices outside Amazon and even punishing independent sellers that did it;

- Leveraging the Prime membership programme to coerce sellers to buy Amazon’s logistics services (Fulfilment by Amazon – FBA).

The complaint is heavily redacted, and we will have to wait at least 14 days to see more of the details, including the secretive Project Nessie, rumoured to be a price-raising algorithm(opens in new window) . Yet, we already know that the FTC argues that with its monopoly power secured, Amazon was able to extract rents from sellers and users, including by:

- Replacing organic results with sponsored ads;

- Biasing results to give preference to its own products;

- Charging steep fees on sellers.

According to the FTC, Amazon has kept making its services more expensive and worse in quality. The fact that this has not led to shoppers and independent sellers choosing a better alternative shows that Amazon’s monopoly power is entrenched and unlikely to weaken.

FTC claims monopoly power enables Amazon to charge monopoly rents

The FTC’s case goes further than any EU agency so far in arguing that by illegally insulating itself from competition, Amazon was able to extract monopoly rents from shoppers and sellers. SOMO’s own research has found that the dynamic that the FTC found in the US is also present in the EU and the UK.

We found, for instance, that Amazon’s income from sellers’ fees has tripled in just five years. In 2022, Amazon collected a whooping €23.5 billion in listing and logistics (FBA) fees from sellers in the EU and UK.

The increase in fees Amazon charged to sellers outpaced increases in sales and cannot be fully explained by higher sales volume. By analysing delivery and storage prices from 2017 to 2023 in Germany, the UK, France, Italy, and Spain, we saw that Amazon has been continuously increasing the prices of these services. The same is happening in the US where, the FTC notes, Amazon increased FBA by nearly 30% from just 2020 to 2022.

With its position insulated from competition, Amazon was also able to add another fee: advertising. Amazon turned a substantial portion of what used to be organic results – ranked according to quality, relevance, and price- into paid-for sponsored content. This sees sellers bidding against each other to be placed in one of the top search results, the ones likely to be seen by shoppers.

According to the FTC, now-advertised products are 46 times more likely to be clicked on. In Europe, this has proved to be a very profitable source of income as it brought in an estimated €2.75 billion in advertising revenue from independent sellers in 2021.

This monetisation of results not only means that Amazon extracts even more from sellers but also that the quality of the service for shoppers is degraded since search results become less reliable and shoppers are steered towards products with higher prices.

The FTC’s case argues that the separate abusive practices magnify one another and together have an even bigger impact. The competition authority, for instance, states that Amazon has price-setting power for the whole e-commerce market given the fact that they can charge ever higher fees to sellers (FBA and advertising) and at the same time prevent sellers from offering the product at lower prices in other online shops. As the antimonopoly researcher Matt Stoller and others have put it, Amazon is enforcing an economy-wide hidden tax.

In spite of the seriousness of these concerns, especially during a cost of living crisis(opens in new window) , so far, no European competition agency has investigated the way Amazon extracts monopoly rents or the impact it has on sellers, shoppers and the wider economy.

Amazon is again being accused of enforcing price parity on sellers

Some of the practices described in the FTC case have already been investigated by European regulators though. In 2013, the German, UK and EU competition regulators prodded Amazon’s price parity clause, which prohibited sellers from discounting products on other marketplace platforms or even in their own online shops. This clause led to much higher prices across e-commerce and blocked price competition from other marketplaces.

European regulators then forced Amazon to stop this practice. At the time, the German Bundeskartellamt celebrated that Amazon had abandoned “price parity clauses for good(opens in new window) ”.

Ten years later, Amazon is again being accused of enforcing price parity on sellers. The FTC argues that Amazon never stopped; it merely removed the clause from the contracts but kept enforcing it via its automated tools. According to the FTC, Amazon relies on extensive web crawling to compare prices on and off its platform. When the company finds that a seller is offering the same product elsewhere at a lower price, Amazon punishes that seller.

Amazon’s executives understood that dropping the price parity contractual clause while still enforcing it via automated processes looked “not only trivial but a trick(opens in new window) and an attempt to garner goodwill with policymakers amid increasing competition concerns”.

German regulators(opens in new window) are again onto Amazon and have spent the past years investigating whether the company is algorithmically controlling the prices of independent sellers. If the regulator finds that this is the case, then there should be lessons taken as to why a company was able to keep the exploitative abuses for an entire decade after the previous investigation.

Prime membership to protect monopoly power

Like the European authorities, the FTC also claims that Amazon is illegally maintaining its power by ensuring that only sellers that use Amazon’s logistics services (FBA) become eligible for the Prime membership programme.

The Italian, EU and UK competition authorities have heavily scrutinised this practice. Regulators found that Amazon has made it essential to pay for FBA if they want to be visible to the vast majority of shoppers on the website.

The FTC adds yet another layer. According to the US regulator, Amazon relaxed its rules in the US in 2015 and allowed sellers to become eligible for Prime even if they did not use FBA via the programme “Seller-Fulfilled Prime”. The FTC states that Amazon saw this programme was “immediately popular with both shoppers and sellers” and internally worried it would threaten its monopoly power. So, Amazon stopped the programme(opens in new window) .

The EU competition department found reasons to be concerned but ultimately accepted Amazon’s proposal to settle the investigation if they would commit to, among other things, not discriminating against sellers(opens in new window) that don’t pay for FBA. Alongside the Balanced Economy Project(opens in new window) and the Open Markets Institute(opens in new window) , SOMO(opens in new window) at the time regretted that the EU was accepting the settlement, especially as it would be difficult to monitor whether Amazon’s automated processes are indeed non-discriminatory.

The UK seems inclined to take a similar route. In July, the UK’s Competition and Markets Authority stated it planned to accept an even weaker offer from Amazon. A decision that both sellers and civil society organisations, including SOMO, questioned.

A more holistic approach needed in the EU

The FTC’s suit confirms the EU’s initiatives to investigate Amazon. At the same time, they show the EU investigations were too timid in places. There is one glaring omission from the FTC’s suit: the role data collection and processing plays for Amazon’s monopoly power. Here, European regulators have gone further and investigated how Amazon uses sellers’ business data to unfairly compete against them. However, once again, EU regulators have simply accepted Amazon’s commitments to end this practice.

This is a crucial point. In Europe, there is a mismatch between the ambition to investigate and the ambition to solve Amazon’s abuses of power. Each abusive practice was investigated individually, and the investigations either ended with a fine or with hard-to-monitor promises from the company that it would change its behaviour. The FTC’s suit doesn’t explicitly mention it, but speculation is that it might seek a structural solution, such as breaking up the company(opens in new window) .

At the EU level, the Digital Markets Act (DMA) has been implemented to address some of Big Tech’s abuses of power. In September, the European Commission announced that Amazon was one of the companies it had identified as being a gatekeeper in the digital economy. Amazon now has until March to guarantee that it complies with the requirements, such as allowing sellers to offer their products on other marketplaces at different prices (Article 5.3) and not obliging business users to pay for one of its services in order to use its platform (Article 5.8). However, even here, regulators, sellers and civil society will need to prioritise monitoring and enforcement of these clauses, especially as much of Amazon’s alleged abuses are done via automated processes.

The DMA alone will not solve the Amazon problem. EU and UK regulators ought to go beyond and investigate Amazon’s pricing policies and their impact on prices on and off the platform, Amazon’s sponsored search results and their impact on sellers and prices, and the impact of Amazon’s growing fees on prices across the economy.

Their investigations need to take note of the FTC and become more holistic to understand the intersecting ways the company protects and reproduces its monopoly power at the expense of everyone else. Doing that will make it much more apparent that Amazon’s problem is structural. As would be the solution.

Do you need more information?

-

Margarida Silva

Researcher

SOMO collaborates on this subject with

Related news

-

-

Digital Markets Act: Big Tech’s pushback faces up to a bold EUPosted in category:Long read

Digital Markets Act: Big Tech’s pushback faces up to a bold EUPosted in category:Long read Margarida SilvaPublished on:

Margarida SilvaPublished on: -

EU health data law rolls out the red carpet for Big TechPosted in category:Long read

EU health data law rolls out the red carpet for Big TechPosted in category:Long read Irene SchipperPublished on:

Irene SchipperPublished on: