Beyond prices

The role of Monopoly Power in global inflation

In our new series of long reads, we examine the manifestation of monopoly power across various sectors and countries. We want to unravel the complex ties between corporate concentration and power, focusing on four key aspects:

- The power to extract profits.

- The power to distribute profits.

- The power to profit without producing.

- The power to extract value from a value chain.

We used data from 51,000 publicly listed firms, over 100 countries, and 180 exchanges over the past three decades to research these four dimensions. We particularly emphasise the largest 1 per cent of publicly listed firms worldwide (by market capitalisation), providing fresh insights and discussing each dimension in detail.

The power to extract profits

This first article takes a look at the power to extract profits. It focuses on the recent short period of profit-driven inflation, which took place from 2020 to 2022. This extraordinary spike in corporate profits needs to be understood as part of the growing monopoly power of the 1 per cent.

The top 1 per cent managed to expand their profits before, during, and after the Covid-19 pandemic and the Russian invasion of Ukraine, showing that these monopolists will thrive in times of upheaval. While the top 1 per cent experienced a 78 per cent nominal rise in gross profits from 2020 to 2022, the bottom 50 per cent of publicly listed firms worldwide saw their profits decline by 29 per cent.

Accelerating Monopoly Power

This difference in the power to appropriate profits follows a pattern that began in the 1980s. Since then, monopoly power has been on the rise, and it has accelerated in the 21st century. In 2017, UN Trade and Development(opens in new window) (formerly UNCTAD) already warned about the emergence of “rentier capitalism” due to growing corporate consolidation. In the same year, the US House of Representatives erected an Antitrust Caucus to investigate and address monopoly issues amidst growing media coverage of “America’s monopoly problem(opens in new window) ”. In 2019, just before the COVID-19 outbreak, the International Monetary Fund(opens in new window) (IMF) highlighted the escalating monopoly power as a key factor in negative global economic trends, including decreased investments, sluggish productivity growth, and widening inequality.

“Sellers’ Inflation”

Subsequently, the pandemic struck, followed by the Russian invasion of Ukraine, which contributed to the sharpest inflation increase since the 1970s. The rise of inflation led to the first global drop in real wages in this century, feeding an ongoing cost-of-living crisis. Isabella Weber identified the remarkable surge in profits in specific, systemically significant sectors – such as energy and food – as a key driver of this unusual inflation spike and termed it “sellers’ inflation(opens in new window) ”.

This inflation was largely driven by historical circumstances that created the conditions for temporal monopolies in these strategic upstream sectors. In response to these price increases, Weber argued, firms downstream increased prices to protect or grow their margins. This led to a much more generalised process of profit-price inflation. As more data emerged, key international economic and monetary institutions, such as the European Central Bank (ECB) and the IMF(opens in new window) , acknowledged the role of corporate profits in fuelling profit-price inflation.

Surging profits

In public debate, this recent surge in profit-price inflation has not been connected to the broader, decades-long rise in global monopoly power. Although the energy sector’s surge in profits was remarkable and largely tied to the unique historical circumstances stemming from the Russian invasion of Ukraine, a broader observation reveals that the entire top 1 per cent managed to uphold their markups more effectively than other firms. This underscores how the structural increase in monopoly power enables major corporations to safeguard their profit margins at the detriment of smaller entities, workers, and public finance in periods of instability.

The persistent rise of monopoly power will likely create more instances of profit-price inflation as we face overlapping and interacting crises (the climate crisis and cost-of-living crisis, the rise of the radical right, and geopolitical tensions). These simultaneous crises interact and create a cocktail of exceptional historical circumstances conducive to the manifestation of sellers’ inflation.

Wealth inequality

This means that we need to have a better understanding of how the long-term consolidation of corporate power and the dynamics that sustain this process relate to the recent sudden rise in temporal monopolies. The price of misdiagnosing the problem and ignoring monopoly power is too high. The erroneous monetary interventions carried out since 2022 have worsened the ability of states and firms to invest in an energy transition. These monetary responses also triggered calls for a new round of austerity that exacerbated the cost-of-living crisis which, like in the early 1930s, has favoured the rise of radical right parties.

A significant indicator of the increase in monopoly power is the substantial growth of markups (the difference between price and cost) among the largest publicly listed firms in major economies. This resurgence of growing monopoly power mirrors historical patterns of corporate consolidation and wealth inequality, showing parallels with the Gilded Age, the previous era of monopoly capitalism.

“This is what monopoly capitalism looks like.

Rising markups for the 1 per cent

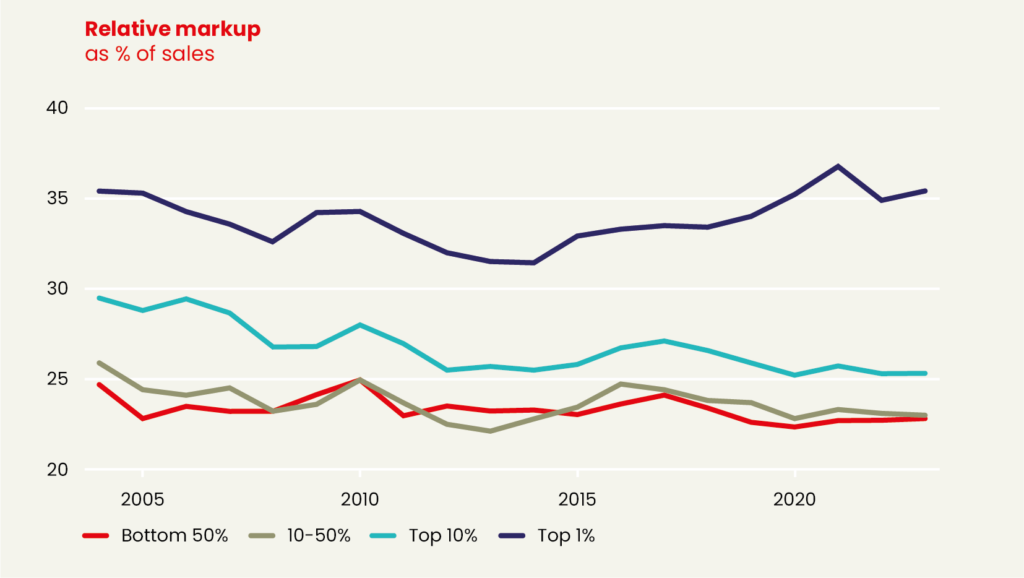

Markups are the amounts that firms add to their costs. Markups can increase in the absence of competition and are therefore a key metric to measure market power. Economists like Jan de Loecker and Jan Eeckhout (opens in new window) showed that markups were three times as high in 2016 as in 1980, an increase driven by the largest corporations. We use the same Worldscope data to approximate markups but use different methods and limit the time horizon to 2005.

With this data set, we examined profits, markups, and the return on assets (gross profits as a share of total assets) to identify which companies managed to increase their share in the global income. Based on their market capitalisation (value on the stock market), we created categories of firms ranging from the largest 1 per cent of the total global population of listed firms to the bottom 50 per cent.

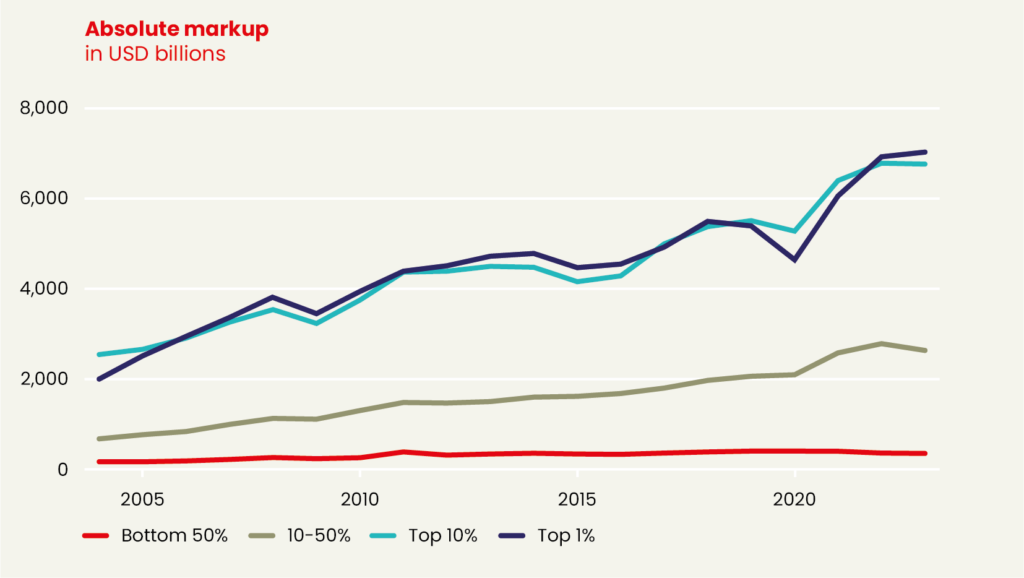

The data shows that from 2005 to 2023, markups were consistently and significantly higher for the 1 per cent largest firms than for firms in any other category. The period of profit-price inflation is also clearly visible in the sudden rise and fall of markups among the 1 per cent largest firms. This contrasts with all other categories, which experienced a decline of markups.

Another way to look at this is by zooming in on the nominal USD value of markups. The value of markups among the bottom 50 per cent of global firms remained fairly stable during this period, moving from USD 182bn in 2004 to USD 347bn in 2023. When adjusted for inflation, the real value actually declined. The top 1 per cent increased the value of its markups from USD 2,038bn in 2004 to USD 6,952bn in 2023. This rise in margins represents the temporal increase in market power in these turbulent years.

If we look at gross profit, which is profit before depreciation, tax, and interest payments, we see a familiar pattern. Similar to the distribution of markups, the 1 per cent takes the lion’s share. Gross profits by the 1 per cent increased from USD 1,778bn in 2020 to USD 3,189bn in 2022, an increase of USD 1,411bn dollars. In contrast, the bottom 50 per cent of global firms saw their gross profits decline from USD 38bn to USD 27bn. While the top 1 per cent experienced a rise in gross profits of 78 per cent, the bottom 50 per cent saw its profits decline by 29 per cent.

Leading the profit-price inflation: Big Oil, Big Pharma, and Big Tech

If we zoom in on the nominal value, we can see the spectacular rise in markups by the 1 per cent in this turbulent age. The sectors Technology (Big Tech), Energy (Big Oil), and Health care (Big Pharma) are the three clear winners in this profit surge. Pharma shows a steady rise in nominal gross profits and jumps 79 per cent after COVID-19 hits in 2020, from USD 352bn to USD 448bn. Tech firms also show a steady increase in nominal value, jumping from USD 945bn in 2020 to USD 1,199bn in 2022. Energy companies, mostly Big Oil, show volatile profits, largely following oil prices. The increase from 2020 to 2022 was a whopping USD 1,349bn, rising from USD 290bn to USD 1,638bn.

Protecting the margins

The energy sector’s growth in profits was exceptional and first and foremost related to the specific historical constellation resulting from the Russian invasion of Ukraine. However, we can see that the wider 1 per cent was able to defend its markups much better than other firms were. This shows that in times of turbulence, the structural rise in monopoly power enables the largest firms to protect their profit margins at the expense of others.

The cost of ignoring monopoly power

The consequences of the brief period of heightened inflation affected people globally: real wages (nominal wages adjusted for inflation) declined, followed by a cost-of-living crisis that led to a marked increase in inequality, amplifying the socioeconomic divide within and between countries.

Data(opens in new window) from the International Labour Organization (I(opens in new window) LO) shows that on average, G20 countries experienced an unprecedented decline in real wages of 2.2 per cent. In some countries, like the Netherlands, the decline in real wages was as high as 5 per cent.

Amid historically unprecedented declines in real wages, central banks in core economies resorted to the blunt instrument of raising interest rates. This misguided (opens in new window) orthodox measure failed to address the root causes of this particular inflation, namely corporate power and instead treated it as a macroeconomic issue described in textbooks. Raising interest rates to temper demand has hampered public and private investments(opens in new window) at a critical moment in the energy transition.

Fuelling crises

Moreover, the increase in interest rates has raised the costs of public debt(opens in new window) , prompting calls for worldwide austerity policies. This will further impede public investments and exacerbate the cost-of-living crisis. The connection between this crisis and the global rise of radical right parties has become increasingly evident(opens in new window) . This mismanagement of the crisis and the resulting political backlash contribute to a complex web of overlapping crises, highlighting the failure to recognise the world’s shift towards growing monopoly power and a winner-takes-most (opens in new window) corporate model.

Looking ahead, the web of overlapping and interacting crises, also known as a “polycrisis(opens in new window) ”, presents all the ingredients for future bottlenecks. Geopolitical tensions have driven up energy prices, leading to sellers’ inflation throughout the system. We appear to be at the dawn of a new era in international trade, where many global value chains shaped by globalisation may need to unbundle. UN Trade and Development has identified the decoupling of FDI flows(opens in new window) and trade flows, potentially signalling the fragmentation of the global economy. The IMF(opens in new window) has observed similar trends regarding the fragmentation of the global financial system.

The energy transition, driven by a corporate agenda, is rife with potential chokepoints as new value chains form and geoeconomic adjustments take place. This phenomenon, known as “greenflation(opens in new window) ”, refers to the inflationary pressures arising from the current transition. Another source of inflation is climate change, termed “climateflation(opens in new window) ”. Extreme weather, droughts, flooding, and rising temperatures impact food prices(opens in new window) and can instigate various supply shocks.

Slowed innovation

These large transformative processes add to the long list of detrimental economic effects(opens in new window) of growing monopoly power, such as slowed innovation, reduced investments, increased rentier income, diminished productivity, and rising income and wealth inequality. The cost of ignoring monopoly power is increasing in this age of turbulence.

Unfortunately, growing geopolitical tensions have strengthened the position of the most powerful firms. Increased competition between the US, the EU, and China to enhance the competitiveness of domestic firms has led to a race for subsidies and tailored regulatory support for domestic superstar firms. The growing linkage between states and firms and the realignment of interests, amidst heightened geopolitical tensions, echoes the previous period of monopoly capitalism, which evolved into an age of imperialism.

Towards solutions

Over the past 40 years, globalisation, market-oriented reforms, the prioritisation of shareholders, and business-friendly competition policies have led to the monopoly-enhancing structure we see today. This structure is embedded in international trade and tax regimes and reinforced by investment and tax treaties that empower corporations and solidify their dominance over democratic institutions.

Luigi Zingales(opens in new window) warned that market concentration creates a vicious cycle: companies leverage their market power to gain political influence, which then enables them to further consolidate their market power. This increasing monopoly power has coincided with a growing plutocracy, where a class of billionaires wields growing influence on decision-making. The entire regime of monopoly capitalism is bolstered by numerous structural elements that will take considerable time to dismantle.

Targeted price controls

The recent surge in profit-driven inflation has highlighted the need for both short-term and long-term measures. Weber suggested that targeted price controls(opens in new window) could curb initial inflationary pressures and prevent them from spreading, drawing on historical examples. Initially, her ideas were met with scepticism. Mainstream economists often overlook corporate profits as a source of inflation, viewing rising prices primarily as a result of surplus demand. Their typical response is to restrain labour to prevent a wage-price inflation spiral. However, Weber’s ideas have gained ground and need to be pushed further.

We need to develop policy tools for targeted price controls to prevent the formation of temporal monopolies that exacerbate inflation. These tools(opens in new window) could include direct price interventions, sector-specific supply-side policies and additional taxes on windfall profits. Moreover, unconventional fiscal policies are needed to protect the most vulnerable and avert a growing cost-of-living crisis. Economists and civil society need a new framework to understand profit-driven inflation and the impact of market power on the economy. This new perspective on monopoly power is especially crucial as we face climate-related challenges, geopolitical shifts, and societal adjustments, enabling the mobilisation of electoral support for policies aimed at curbing escalating corporate power.

Include trade

The Centre for Research on Multinational Corporations (SOMO), along with other civil society organisations, has put forward several proposals to tackle the broader underlying issues in the EU that bolster monopoly power. These policy suggestions include a comprehensive overhaul of competition policy and a more expansive regulatory approach to monopoly power that incorporates trade policy.

Rebalancing our economy and curbing monopolistic dominance will undoubtedly be a long and challenging journey. However, this reality should not discourage efforts to explore and implement alternatives(opens in new window) . In today’s turbulent times, ignoring the influence of corporate power is simply not an option.

Do you need more information?

-

Rodrigo Fernandez

Senior researcher

Related news

-

The power to extract value from the value chainPosted in category:Long read

The power to extract value from the value chainPosted in category:Long read Rodrigo FernandezPublished on:

Rodrigo FernandezPublished on: -

-

Taking Stock: 50 Years of prioritising shareholdersPosted in category:Long read

Taking Stock: 50 Years of prioritising shareholdersPosted in category:Long read Rodrigo FernandezPublished on:

Rodrigo FernandezPublished on: