Carbon offsets often disenfranchise communities

Myth: “Carbon offsets bring added benefits to communities”

SOMO’s ‘Facing the facts: carbon offsets unmasked’ series debunks eight myths promoted by the offset industry.

Carbon market proponents claim:

Industry proponents argue that carbon offsetting is not just about reducing emissions but that projects also bring benefits for communities and ecosystems, such as building schools, offering employment, promoting gender equity, and protecting biodiversity. Self-regulated standards in the voluntary carbon market claim to have rigorous safeguards and requirements to verify that communities benefit. Major corporations buying carbon credits claim to be supporting social benefits and biodiversity in the Global South.

Reality check:

There are serious problems with the industry’s claims that carbon offset projects benefit communities. Firstly, in most cases, the offset industry offers to (or imposes on) communities development-style projects or initiatives, which are ‘given’ in exchange for community members modifying or ceasing their livelihood activities. At the start of the offset project process, the communities recognised as ‘stakeholders’ become dependent on the project developers, who hold all the information and have a vested interest in the community acting in line with their plans. Because many of the purported benefits are linked to how much the project developer can sell credits for, as projects continue, communities frequently find themselves dependent on volatile market prices for carbon credits. The power dynamics involved are significant. Second, in many cases, far from benefitting from carbon offset projects, the rights of communities are trampled on(opens in new window) . Forest-based offset projects have exacerbated conflicts over land, increased insecurity of tenure and access to livelihoods, and led to forced evictions of many communities.

‘Benefits’ enforce dependency on project developers and volatile carbon markets

Communities affected by carbon offset projects are rarely adequately informed(opens in new window) about the risks involved with so-called benefit-sharing agreements (where these are even offered). Communities frequently do not know what the projects are about until they are being implemented. One study(opens in new window) of 47 carbon offsetting projects observed that “only one single project has published evidence of having distributed benefits that go beyond mere payments for results” (such as salaries for work done). The same report highlighted that there is no uniform definition of “benefit-sharing arrangements” in the voluntary carbon market, making the concept susceptible to manipulation.

Many forest-based offset projects place limitations on the use of land and forests by communities, jeopardizing their subsistence economies in return for low wages for some – not all – community members or for unstable benefits. The Berkley Carbon Trading Project (opens in new window) noted that: “These restrictions, when enforced, commonly fall hardest on more vulnerable households and communities”. The Berkley report pointed out that the safeguard policies of the self-governing offset industry, which are supposed to ensure communities are not harmed, are often treated as voluntary guidance or a check-box activity. Read more about the conflicts of interest in the offset industry here.

Because the project developers often give the ‘benefits’ to communities based on the sale of carbon credits, reports of human rights abuse or social harms on offset projects can lead to a loss of such benefits. If issues are exposed, corporate customers may stop buying credits from a particular project, jeopardizing the benefits communities were promised the project would bring. In this context, communities can end up in a ‘Catch-22’ situation with serious problems suppressed because of the possible consequences. The system can also create serious internal conflicts when only some in the community enjoy jobs and other benefits while others experience adverse impacts of the project.

Human rights abuses linked to the carbon offset industry

In recent years, numerous media(opens in new window) , academic(opens in new window) and civil society(opens in new window) reports have exposed serious human rights abuses affecting people living within or near the boundaries of forest-based carbon offset projects.

In 2017, CIFOR(opens in new window) , an organisation broadly positive about carbon markets, reviewed 85 journal articles on Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation (REDD+) processes and projects, which is the main scheme for forest-based offset projects. The analysis revealed “multiple allegations of abuses of the rights of Indigenous Peoples” in the context of REDD+ readiness and implementation. The allegations included violations of Indigenous Peoples’ rights to participation, recognition and protection of traditional lands and redress.

The reports of human rights abuses have continued to mount. In 2023, SOMO and the Kenya Human Rights Commission published a report exposing systemic sexual harassment and abuse at one of the most celebrated offset projects: the Kasigau Corridor REDD+ project in Kenya. The abuse, enabled by the unequal power dynamics between some senior officers of the company behind the project and local people, persisted for at least 10 years.

In 2024, Human Rights Watch published a report(opens in new window) on another celebrated offset project: the Southern Cardamom REDD+ project in Cambodia. Their investigation documented a flawed consultation process and how the Indigenous Chong people, having lived in the Cardamom mountains for centuries, faced forced evictions and criminal charges for farming and foraging in their ancestral territories due to the offset project.

In 2024, the extent of the harmful impacts on human rights led the UN Special Rapporteur on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, Francisco Calí Tzay(opens in new window) , to call for “a permanent moratorium, or at least a moratorium” on carbon markets.

Land rights and large-scale investments

Land-based offsets usually require extensive areas of land and forests. Where people whose land is affected have insecure tenure or land rights, which is frequently the case for Indigenous Peoples and traditional communities, the risks of land grabbing are significant.

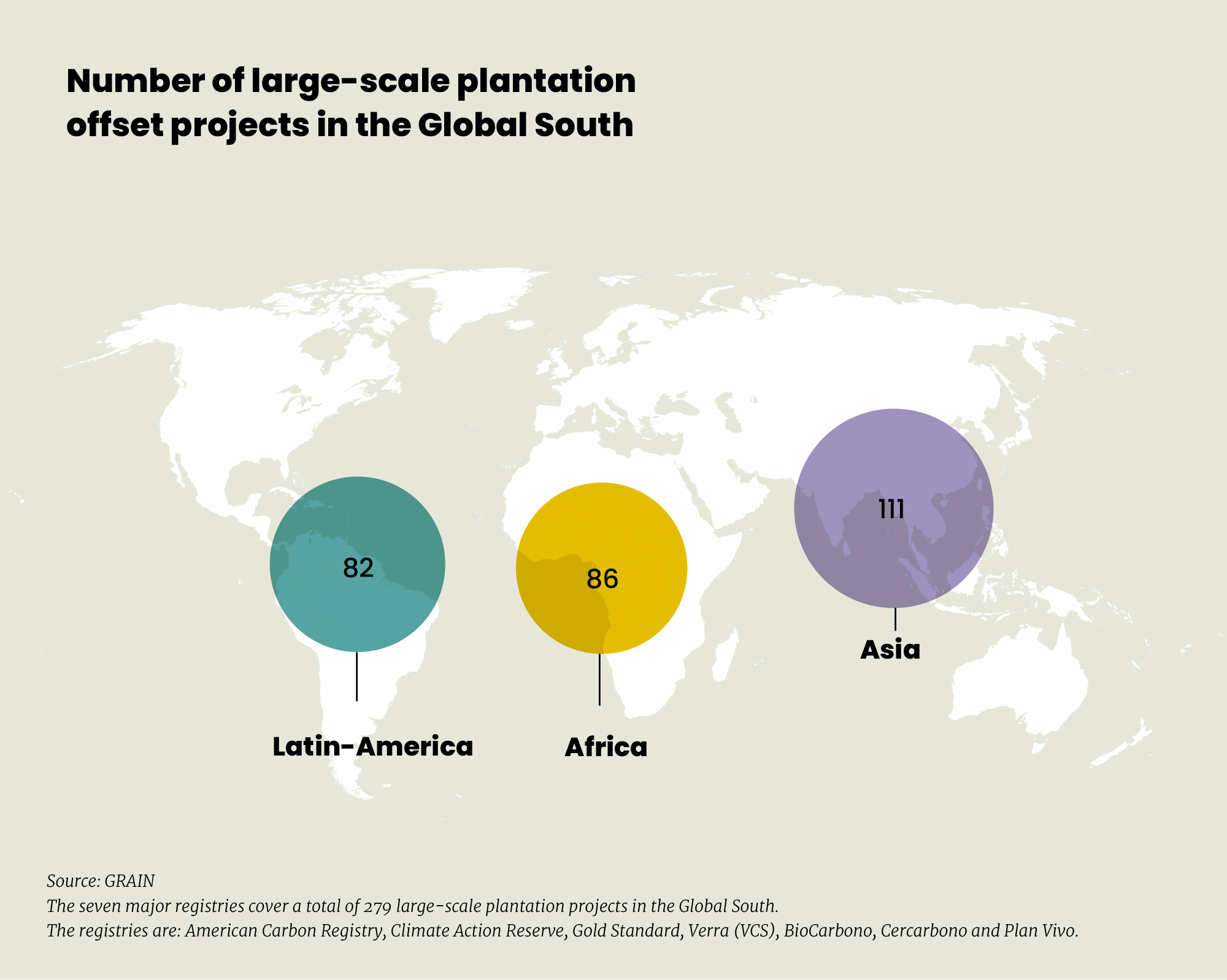

A 2023 report(opens in new window) by Carbon Brief found that “Indigenous Peoples have been forcibly removed from their land because of carbon-offsetting in the Republic of the Congo and Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), the Brazilian, Colombian and Peruvian Amazon, Kenya, Malaysia and Indonesia.” Research by the NGO GRAIN(opens in new window) shows how much land is currently being used for large-scale plantation offset projects in the Global South, with 279 projects covering 9.1 million hectares – an area roughly the size of Portugal. Although Africa has fewer projects, the amount of land affected is more than double that in either Asia or Latin America. The analysis from GRAIN covers only one kind of forest-based offset project. It does not include projects covering the preservation of forests, for example. The amount of land under offsetting in the Global South is, therefore, likely to be much greater.

The abuses and risks associated with offsetting, including land grabbing and forced evictions, will only intensify if the industry continues to expand. Yet, this is exactly what is planned. According to the 2023 update on the Land Gap Report(opens in new window) , governments globally have proposed approximately 1 billion hectares of land for offsets as part of their climate mitigation pledges. This is more than the combined areas of South Africa, India, Turkey and the European Union. And this number does not even consider the projects established and planned by corporations, which are outside the governmental pledges.

This is extremely concerning since, according to the Land Gap Report(opens in new window) , the vast majority of the areas under governmental pledges are located on the customary lands and territories of Indigenous Peoples and local communities. We have already seen how investors(opens in new window) have negotiated deals with governments in the Global South to take control of large tracts of land and forests for offsetting purposes.

In a nutshell

Far from benefitting communities and Indigenous Peoples, carbon offset projects frequently lead to abuse and often require people to give up their livelihoods and control over their territories in return for uncertain and volatile carbon market benefits. Despite the growing number of reports of abuses of the rights of Indigenous and traditional communities, the carbon offset industry is expanding.

What’s the alternative? Read more about how to think outside the ‘offset box’ at the end of this series.

More from the blog series

-

To achieve real emission reductions, carbon offsetting needs to endPosted in category:Long read

Joanna CabelloPublished on:

Joanna CabelloPublished on: -

The offset industry, riddled with conflicts of interest, is not fixablePosted in category:Long read

Ilona HartliefPublished on:

Ilona HartliefPublished on: -

Regulation to reduce CO2 emissions is the most effective way to address climate changePosted in category:Long read

Joanna CabelloPublished on:

Joanna CabelloPublished on: -

Carbon offsets are an obstacle to real climate solutionsPosted in category:Long read

Ilona HartliefPublished on:

Ilona HartliefPublished on: -

A brief history of colonialism, climate change and carbon marketsPosted in category:Long read

Joanna CabelloPublished on:

Joanna CabelloPublished on: -

Carbon offsets are diverting money away from climate action in the Global SouthPosted in category:Long read

Ilona HartliefPublished on:

Ilona HartliefPublished on: -

-

Scaling up carbon markets means scaling up emissions and abusePosted in category:Long read

Joanna CabelloPublished on:

Joanna CabelloPublished on: -

Climate leadership means reducing real emissionsPosted in category:Long read

Audrey GaughranPublished on:

Audrey GaughranPublished on:

Do you need more information?

-

Joanna Cabello

Senior Researcher -

Ilona Hartlief

Researcher