ECT is an obstacle

ISDS not removed from modernised text

The Energy Charter Treaty (ECT) is a 1994 international treaty(opens in new window) that protects foreign investment in the energy sector. Under the treaty, energy companies and their shareholders can sue governments in case new regulations jeopardise their expected corporate profits, including climate measures.

ECT members have been discussing modernising(opens in new window) the treaty since 2017. An agreement in principle(opens in new window) was reached on 24 June 2022 and will be submitted to ECT members for approval at the Energy Charter Conference on 22 November. Unanimity is required in this regard. And although confidential, the text of the modernised treaty was leaked(opens in new window) through the media in early September.

What is clear from the new text is that the proposed adjustments are insufficient to bring the treaty in line with the Paris climate goals: the adjustments actually introduce new risks of arbitration cases.

What are the main outcomes of the modernisation process?

- The renewed treaty continues to provide indefinite protection for existing and new fossil fuel investments. This goes against the International Energy Agency(opens in new window) ‘s call for no new fossil investments, and for existing fossil investments to be phased out, in order to meet the Paris climate targets.

- The amended ECT includes a ‘flexibility mechanism’ that allows ECT members to phase out fossil fuel protection on their territory. Only the EU and the UK have opted for this. Under this mechanism, the following applies:

- New investments in fossil fuels made after 15 August 2023 will no longer be protected. However, there are exceptions for certain gas-related investments: those are still protected until 2030, or in some cases even until 2040. This includes, for example, gas-fired power plants that are ‘significantly harmful’ according to the EU’s sustainable investment taxonomy(opens in new window) .

- Existing fossil fuel investments made before 15 August 2023 remain protected until 10 years after the new treaty enters into force, and in some cases until the end of 2040. This means that current investments in oil, gas and coal will remain protected until at least 2033, while they will have to be largely phased out by 2030 to meet climate targets. As a result, the flexibility mechanism is not in line with the Paris climate agreement.

- The new ECT extends investment protection to new energy sources and technologies, such as hydrogen, anhydrous ammonia, biomass, bio-gas and synthetic fuels, and carbon capture, utilisation and storage ( ). Please note that the latter does not apply within the EU: CCUS is excluded from protection here. The extension of investment protection to these technologies increases the risk of corporate claims and thus constitutes an additional obstacle to the energy transition. UNCTAD(opens in new window) recently warned that governments should have sufficient flexibility for necessary policy experiments for climate adaptation.

- The investment protection provisions include some adjustments to better safeguard the so-called ‘right to regulate’ for governments. These adjustments are in line with recent EU trade treaties, such as the CETA treaty with Canada. Nevertheless, even the modernised ECT provides a legal framework in which investors’ interests take precedence over societal interests. Investors can still invoke widely used standards such as ‘fair and equitable treatment’ and ‘indirect expropriation’. Recent decisions(opens in new window) by arbitration panels show that including more detailed provisions or exceptions in treaty texts does not necessarily increase or secure the policy space of governments.

- New provisions on sustainable development and corporate social responsibility confirm treaty parties’ commitment to climate policy and energy transition, but hardly create any new obligations.

- The controversial and widely criticised investor-state dispute settlement (ISDS) mechanism under which investors can bring claims remains unaffected. The problematic ‘sunset clause’ also remains unchanged, meaning that on exit, the treaty will remain in force for another 20 years.

- The modernised ECT aims to exclude arbitration cases between an investor from an EU member state against another EU member state. This follows the ruling of the European Court of Justice, which ruled in September 2021(opens in new window) that intra-EU arbitration based on the ECT violates European law. However, arbitral tribunals simply disregard this ECJ ruling, calling it “completely irrelevant(opens in new window) ” to the admissibility of claims under the ECT. The new provision will only take effect once the new treaty enters into full force. That will not happen until three-quarters of ECT countries have ratified the treaty; a process that could take years.

- The European Commission is therefore proposing an addition(opens in new window) to the treaty to effectively rule out intra-EU arbitration. The Commission also argues for an earlier implementation on 15 August 2023(opens in new window) , even though the treaty still has to pass all national parliaments by then. Moreover, there is still considerable uncertainty about the compatibility of broader aspects of the ECT with European law.

Extending membership to countries in Africa, Asia and Latin America

It is expected that with the new treaty, membership expansion(opens in new window) will also take off. The Energy Charter Secretariat is promoting the ECT globally as an important tool for energy transition. Several countries, including Pakistan, Nigeria and Uganda, are about to join. However, numerous studies show that the ECT (or other investment treaties) hardly play any role in attracting new investments, let alone in renewable energy. At the same time, European investors in oil, gas and coal can claim large damages for climate and energy measures on the basis of the new treaty, putting the energy transition at risk even in new member states.

It is up to the EU

EU member states will soon discuss approval of the modernised ECT, ahead of November 22. A qualified majority is needed to approve the ECT at EU level. Several countries are considering leaving the ECT. Poland’s parliament(opens in new window) has approved a law to leave the ECT. Spain(opens in new window) too has now started the procedure to exit. In the Netherlands(opens in new window) , the Lower House passed a motion to leave the ECT before the summer and will hold a committee debate on the Dutch commitment on 18 October(opens in new window) .

If the EU does not approve the new treaty, the Union will have to leave the existing treaty, given the European Court of Justice ruling. In doing so, the EU will have to neutralise the ‘sunset clause’. This is legally possible(opens in new window) by drafting a mutual treaty that will make this clause inapplicable between EU member states. This will significantly reduce the risk of arbitration cases for the EU and EU member states, compared to the 10-year transition period proposed by the EU.

With increasing urgency for climate action, exiting the Energy Charter Treaty this is the only right choice.

Do you need more information?

-

Bart-Jaap Verbeek

Researcher

Related content

-

COP27: EU adoption of a “modernised” Energy Charter Treaty would open door to more climate chaosPosted in category:Opinion

Bart-Jaap VerbeekPublished on:

Bart-Jaap VerbeekPublished on: Bart-Jaap Verbeek

Bart-Jaap Verbeek -

The Netherlands wants to exit Energy Charter TreatyPosted in category:News

The Netherlands wants to exit Energy Charter TreatyPosted in category:News Bart-Jaap VerbeekPublished on:

Bart-Jaap VerbeekPublished on: -

Urgent call to the Dutch government: exit the Energy Charter Treaty nowPosted in category:News

Urgent call to the Dutch government: exit the Energy Charter Treaty nowPosted in category:News Bart-Jaap VerbeekPublished on:

Bart-Jaap VerbeekPublished on: -

-

-

Pull the plug on the Energy Charter TreatyPosted in category:Opinion

Bart-Jaap VerbeekPublished on:

Bart-Jaap VerbeekPublished on: Bart-Jaap Verbeek

Bart-Jaap Verbeek -

Posted in category:Publication

-

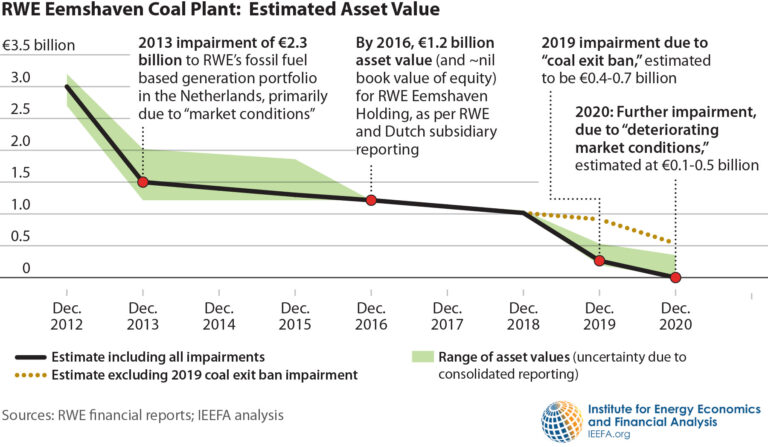

Research undermines billion euro “compensation” claims by German energy companies for Dutch coal phase-outPosted in category:News

Research undermines billion euro “compensation” claims by German energy companies for Dutch coal phase-outPosted in category:News Bart-Jaap VerbeekPublished on:

Bart-Jaap VerbeekPublished on: -

Coal company sues the Netherlands over controversial investment treatyPosted in category:NewsPublished on:

Coal company sues the Netherlands over controversial investment treatyPosted in category:NewsPublished on: