Fool’s Gold

How Canadian mining company Eldorado Gold is devastating the environment and local livelihoods in Greece and avoiding taxes by using Dutch mailbox companies

This story is based on SOMO research into Eldorado Gold’s tax avoidance structures and its human rights impact in Greece.

The damage caused by Eldorado Gold in Greece

“The mining project is huge. Immense. Their plan is to evict three villages: Megali Panagia, Gomati and Palaiochori. That means, what, 5,000 people? The government’s new framework plan does not mention our villages at all. It is as if we already don’t exist.” Pigi, a local resident of Megali Panagia

Barbed wire, check points, private security guards and surveillance cameras cut across the hills overlooking the northern Greek peninsula of Halkidiki(opens in new window) . Until last year, these picturesque hilltops were covered with 400-year-old oak and beech tree forests.

Over the past two years, the Canadian mining company Eldorado Gold has clear-cut a vast swathe of ancient, old growth forest to build Greece’s first and biggest open-pit and underground gold mine. The mammoth project also includes a copper-gold processing plant, two additional underground mines and several mine waste dump sites, with 150m high dams to divert toxic waste from mountain spring water.

Independent scientific reports predict that the Skouries mine – initially almost a kilometre deep and the same in diameter – will cause irrefutable and permanent environmental damage. Soil erosion, flooding, water depletion, as well as air and groundwater pollution from heavy metals and asbestos, will permanently destroy biodiversity in the area and pose a serious threat to people’s health.

Photo: Nikos Pilos

Damage done by Eldorado Gold | Barbed wire, armed check points and surveillance cameras cut across the Halkidiki hills, which were until last year covered with 400-year old oak and beech tree forests

Fool’s gold

noun [U] UK /ˌfuːlzˈɡəʊld/

- yellow metal that looks like gold

- something that you are very attracted to that you later find is not worth very much

The Skouries old-growth forest is a natural aquifer and main freshwater source that provides water for the entire region, including 16 villages. The area has a diverse and delicate ecosystem that’s popular for its local honey, fisheries and sandy beaches.

In an area with pristine emerald beaches, the coastline near Eldorado’s Stratoni mine has been closed for bathing and fishing since the 1980’s due to toxic mining waste while groundwater is polluted with acid and heavy metals leaching from the mine.

Local people in Halkidiki and Thrace, where Eldorado Gold owns two other mines, have been speaking out against mining in this region for almost two decades. Locals know from firsthand experience that the so-called benefits of mining cannot possibly outweigh the potential losses. They say the mines will endanger lives through contamination and pollution, while destroying local livelihoods that depend on tourism, small-scale farming, forestry and fishing.

Protests, court cases and demonstrations against the Skouries mine have often turned violent. Local villagers fighting to hold onto their homes have been beaten and shot with rubber bullets, tear gas canisters and stun grenades by armies of police. Some protesters have been jailed, many have been illegally forced to give DNA samples, and others have been charged with being part of a criminal organisations.

Greek parliamentarians have evidence that Eldorado Gold has been subsidising the local police force to work as the company’s private security guards. Amnesty International launched a human rights abuse case in 2013 against the Greek government for its role in the brutal police repression and criminalisation of the local resistance movement.

Photo: Nikos Pilos

Protest | Locals protesting against Eldorado Gold’s mining operations.

How Eldorado Gold avoids tax through Dutch mailbox companies

“In the current international fiscal environment, the Dutch holding company regime is still the most popular holding regime in the world. The primary reason for this popularity is its tax efficiency (mostly 0% tax), the flexibility of Dutch corporate and tax law and its relatively low cost of incorporation and annual maintenance.”

Tax Consultants International

Barbara Strozzilaan 101 is a mailbox on the wall of a non-descript office building on the outskirts of Amsterdam between a massive mobile phone mast and a junior hockey club. It is used by 70 international companies. A Dutch-based mailbox company is only a postal address and not an actual business with commercial activities in the Netherlands. It is used mainly for the purpose of transferring money within a company from high- to low-tax countries. Twelve of the 70 mailbox companies registered at Barbara Strozzilaan 101 are owned by Eldorado Gold. Together these companies have a total asset value of around €2 billion.

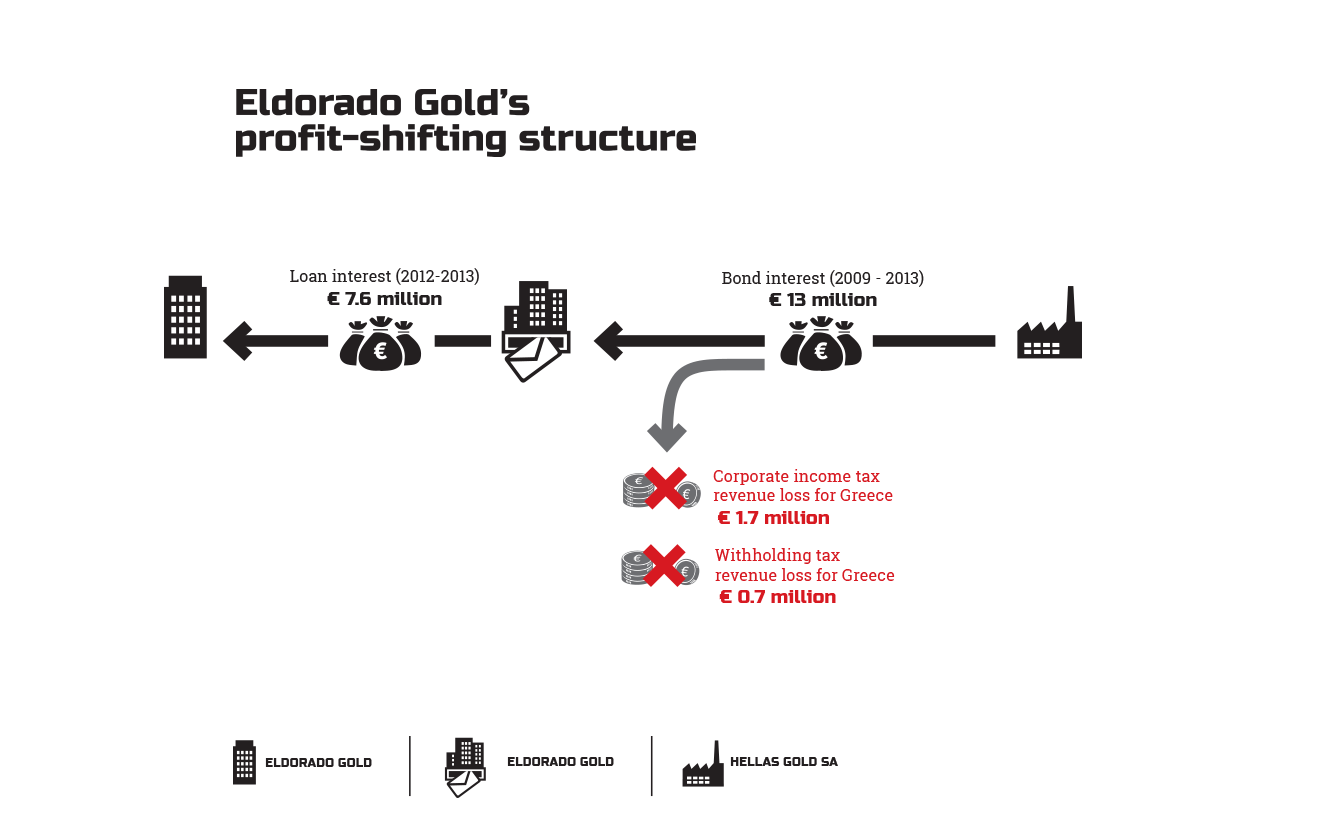

With the help of crafty Dutch tax experts, Eldorado Gold began setting up an elaborate intra-company lending scheme in 2012 between its business in Greece, empty mailbox companies in the Netherlands, and an office in the tax haven of Barbados. The Greece-based subsidiary Hellas Gold finances its operations by issuing bonds that are bought up entirely by Dutch (mailbox) companies. The Dutch companies in turn are financed by loans from Eldorado Gold’s Babardos-based company. Interest payments on the bonds and loans, both going from Greece to the Netherlands and from the Netherlands to Barbados, remain virtually untaxed.

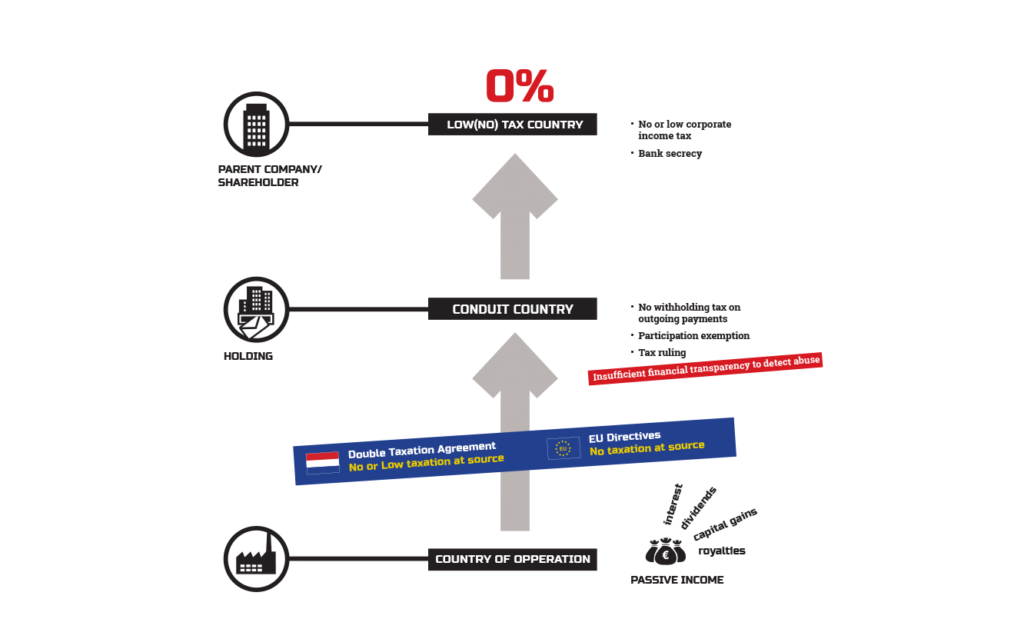

Profit shifting is when income is shifted from a subsidiary with economic activities in a regular tax jurisdiction to an empty shell subsidiary in a low tax jurisdiction. Costs are thus created or inflated in operational subsidiaries and subtracted from the profit, reducing corporate income taxes.

The report only looked at one tax avoidance opportunity, namely, profit-shifting through loan financing: Eldorado Gold’s Greece subsidiary Hellas Gold SA finances its operations by issuing bonds, which are a form of loan and on which the subsidiary has to pay interest to bond holders. All bonds have been bought up by Dutch subsidiaries, two of which are financed by loans from a Barbados subsidiary. Interest is therefore shifted from Greece to the Netherlands and from there to Barbados.This Dutch financing structure – rather than direct financing by the Canadian parent company – has saved Eldorado Gold (and cost the Greek government) more than €700,000 in withholding taxes in two years and €1.7 million in corporate income taxes in five years.

Facilitated by the Netherlands, Eldorado Gold put a system in place to avoid paying corporate taxes by exploiting tax treaties, loopholes and national and EU legislation wherever possible. Eldorado Gold’s carefully designed arrangement also inflates costs in Greece, which reduces the current (and possibly future) taxable profits. This scheme results in less corporate income tax paid in Greece, which is money that is desperately needed by the state to pay for essential public services including healthcare, security, infrastructure and education.

This form of aggressive tax avoidance is legal and even promoted by the EU and the Dutch government, which is also in the business of offering secret and tailor-made tax deals for companies that set up empty mailbox companies in the Netherlands.

Global companies use aggressive tax avoidance schemes to shift income from high-tax to low-tax jurisdictions to avoid paying tax that is rightfully owed to governments where income is earned and profit is generated.

There is no indication that Eldorado Gold’s investment in gold mines in Greece will bring any fiscal benefits to the country’s ailing economy.

Photo: Nikos Pilos & Ilona Hartlief

EU tax havens erode public finances in Greece

“It may be legal, but it is immoral to allow the plunder of natural resources in any part of the world for the benefits only of the investors.”

Jamie Kneen, Canada Mining Watch

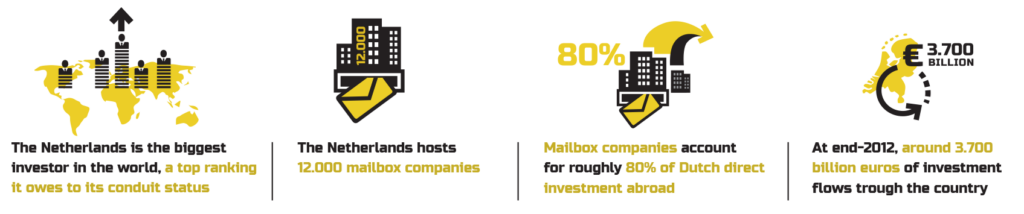

Tulip fields, windmills, the Van Gogh Museum, coffee shops…? What do you think is the most lucrative tourist attraction for the Netherlands? You may be surprised that the highest-earning attraction is actually a sophisticated, entrenched, structural system of tax breaks offered to multinational companies when they route their money through empty Dutch mailbox companies.

The Netherlands is one of the biggest enablers of aggressive corporate tax avoidance in the world and has built a booming industry around promoting and selling Dutch tax services to global companies.

Although the Netherlands has fewer than 17 million residents and a landmass that could fit inside a quarter of the US state of Florida, the Netherlands is actually the biggest investor in the world – even bigger than the USA or China. This is because of the amount of investment money passing through Dutch mailboxes every year.

Foreign direct investment (when a company invests from one country into another) both into and out of the Netherlands amounted to trillions of euros in 2012. However, 80 per cent of that money only passed through the Netherlands using Dutch mailboxes.

The Dutch state plays a central role as a ‘conduit’ in facilitating this global movement of money through the Netherlands, essentially rerouting foreign companies’ capital to avoid tax in other jurisdictions.

Since these mailbox companies are legally registered, they get access to Dutch fiscal and tax treaty benefits, without actually having any real activities or employees in the Netherlands. Promoted to international companies as a way of avoiding double taxation, what the Dutch actually offer as a conduit country is the route to double non-taxation.

The Netherlands and Luxembourg are the two biggest foreign direct investors in Greece, accounting for almost 40 per cent of investments. Around 80 per cent of Dutch investment into Greece is routed through Dutch mailboxes, proof that the Netherlands is a financial ‘conduit’ for most foreign companies doing business there. These same companies avoid paying their fair share of Greek taxes by routing funds through Dutch mailboxes.

The Netherlands is actually facilitating the erosion of Greece’s tax base on a very wide scale, while assuming no responsibility for the economic devastation in Greece and the severe human suffering caused by the loss of essential public services, exacerbated by the current economic crisis. Rather than owning up to its dubious role in undermining Greece’s means of paying for public services, the Dutch government firmly backs the austerity measures imposed by the Troika (the European Commission, the European Central Bank and the International Monetary Fund). These measures have had a devastating economic and social impact in Greece.

The crisis in Greece: Economic and humanitarian

“Austerity has failed in Greece. It crippled the economy and left a large part of the workforce unemployed. This is a humanitarian crisis.” Alexis Tsipras, current Prime Minister of Greece

Greece is experiencing its worst economic crisis since World War II with historians and economists comparing the situation now to the “gold standard of economic catastrophe” or the USA during the Great Depression.

One in four people is out of work. Youth unemployment – among young people who are still in the country – stands at 60 per cent. Child poverty in Greece grew to 40.5 per cent in 2015 from 23 per cent in 2008, while cuts to health services have led to devastating social and health consequences. The medical journal The Lancet describes the lack of health services from spending cuts, unaffordable health insurance due to rising unemployment and the rapidly increasing rates of suicides, mental illness and treatable infectious diseases across Greece as a “public health tragedy”.

Austerity measures have led to an economic and humanitarian crisis in Greece. These measures were imposed following the financial bailout by the Troika and include labour market deregulation, large-scale privatisations, cuts in government spending and fiscal consolidation or raising taxes.

Greece has had two economic adjustment programmes imposed, first in 2010 and the second in 2012. Rather than helping the Greek state manage the crisis, more than 75 per cent of the Troika funds was channelled back to the European financial sector – including to German, French, British and Dutch banks – leaving very little for Greece. Moreover, this toxic mix of cutting public spending and privatising public services has done anything but lead to growth. In the six-year period from 2007-2013, the economy shrank by nearly one-fifth, domestic demand fell by one-quarter, investment fell by one-half, and public debt increased by more than one-third.

The Greek crisis has been complicated and worsened by foreign companies like Eldorado Gold that avoid paying taxes in Greece. The way Eldorado Gold routes finances through Dutch mailboxes effectively wipes out profits that will be generated in Greece from the Greek mines, which should be rightfully taxed in Greece and used by the Greek government to pay for essential public services.

Greece has a historically questionable track record of collecting taxes, as well as giving Greek oligarchs – including shipping magnates with their tax-free status, construction companies and football clubs –substantial tax breaks. The Greek tax system was already skewed against salaried workers.

But when the global economic crisis began to unravel in 2009 and the Troika conditions were imposed on Greece, the burden of increased Greek taxation was shifted even more from companies to working and middle class individuals and families, many of whom now live in conditions of extreme deprivation, or worse.

Photo: Orhan Tsolak

Greek crisis | Waste pickers walk along a street in the northern Greek port city of Thessaloniki looking for salvageable items in the city’s rubbish.

Call to Action

“It’s citizens doing politics. If the citizens don’t get involved in politics, others will. And that opens the door to them robbing you of democracy, your rights and your wallet.”Pablo Iglesias, Secretary General of Podemos

A historical opportunity

At the core of the current political and economic system in Europe are policies that generate financial and social losses at the expense of the public. At the same time, private profits are actively being promoted and protected by European governments. In Greece, this status quo has recently been shaken by the overwhelming victory of the anti-austerity party SYRIZA.

In Spain, 150,000 people recently gathered in Madrid’s Puerta del Sol for a rally by the one-year-old left-wing party Podemos (‘We Can’), which stands a real chance of winning in this year’s general elections. The mandate given by the public to these new political parties is clear: stop austerity measures and redistribute wealth from the rich to the poor. This demand provides us with a unique window of opportunity to change the political responses of Greece, Spain and the EU to the European debt crisis and to develop alternatives that promote social and economic justice.

In stark contrast with the governments of the past, the newly elected Greek government has publicly opposed Eldorado Gold’s goldmine project. The new Deputy Minister of the Environment, Yannis Tsironis, announced that the government will review all permits issued to Eldorado Gold. However, a cancellation of the contract has not yet been announced and major interests are at stake: US$ 2.7 billion – almost half of the company’s global assets – are invested in Greece. A solution will also have to be found to any job losses resulting from a closure or scaling down of the mines.

Photo: Louisa Gouliamaki

Greek crisis

There is now a unique opportunity to close the EU’s tax gap and to change the bail-out policies of the Troika that have served largely private interests until now. Both are leading to a massive redistribution of wealth from the poor to the rich. German, French and other EU banks have given risky loans with high profit margins to Greece. When the loans could not been repaid, the Troika bail-out turned this private debt into public debt. In 2010 the Greek public debt stood at 110% of Gross Domestic Product (GDP). After the Troika programme, this figure increased to 175%. The Greek crisis is in actual fact a crisis of European banks.

The corporate tax avoidance case of Eldorado Gold – as well as the vast amounts of money flowing through Dutch and Luxembourg mailbox companies out of Greece – illustrate that the responsibility for the Greek tax gap lies not only with the Greek state either. Greece’s Finance Minister Yanis Varoufakis recognised (opens in new window) that Greece “has a major problem with tax evasion through transfer pricing” and urged his German and European colleagues to support a cross-border solution. The Netherlands, Luxembourg and the EU have fiscal and investment regimes that facilitate tax base erosion and prioritise private above public interests. This is denying Greece much-needed domestic resources to pay for basic social services.

What has contributed to this changing political landscape is the (re-)emergence of grassroots, community-led solidarity movements. Social and economic support initiatives have developed in response to failing state services. However, as well as offering direct support, they are also practising democratic decision-making and collective action. One journalist commented on Greece’s solidarity movement: “It’s a whole new model – and it’s working”. This quote is telling on two accounts.

First, grassroots democracy and solidarity are not new but have a thriving history in Europe, yet their depiction as being novel shows the extent to which the Thatcherite ideology of ‘No Alternative’ (to capitalism) and ‘No Society’ (only individuals) has pervaded not only European politics but also the public imagination. Second, this comment suggests that the public imagination may currently be shifting towards the exploration of alternatives. Whether it will succeed is a matter of demonstrating the viability of social communities and resistance to market rule.

Protest and solidarity

Democratic and egalitarian economic alternatives are possible, but systems only change when people organise and hold the powers that be accountable. Then decision-makers will be forced to create conditions under which alternatives can be explored and implemented. An economic justice alternative thus also requires an alternative to the current democratic system, which is closely intertwined with business interests.

A necessary counter power requires broad-based movements built on democratic principles and solidarity. An alternative economic model for Europe that serves the public interest should be called for by all European citizens. This requires solidarity for Greece, based on the understanding that there is a material shared interest between ordinary people in all European countries to develop these alternatives.

After all, the money lent to Greece under severe austerity conditions has ended up in European banks. Macro-economic imbalances require political-economic solutions, and the first steps in the right direction would be debt auditing, to analyse and criticise where public funds end up, as well as tackling tax dodging. European citizens should advocate for an end to their countries’ support for austerity measures in debt-ridden European economies, and policies that erode other countries’ public finances.

Building knowledge

Alternatives require knowledge, ranging from technical to political expertise. On a daily basis, movements, academics and organisations are building this expertise as an alternative to dominant institutions and political and economic elites. Inspirations for alternatives include trade unions, civil society groups, community groups and political organisations. Tapping into or contributing to existing organisations is one mode of action. ‘Street level’ community organising – in neighbourhood committees and self-organised economic production – can develop into flourishing alternatives to the current economic model.

For more information and examples of concrete actions, see the following organisations and campaigns:

- TroikaWatch(opens in new window)

- Greek debt auditing campaign(opens in new window)

- Global campaign to end corporate impunity(opens in new window)

- Blockupy (Dutch)(opens in new window)

- Blockupy (German)(opens in new window)

- Ander Europa (Dutch)(opens in new window)

Related news

-

The Netherlands – still a tax haven Published on:

Arnold MerkiesPosted in category:Publication

Arnold MerkiesPosted in category:Publication Arnold Merkies

Arnold Merkies

-

Tax avoidance in Mozambique’s extractive industriesPosted in category:Long read

Tax avoidance in Mozambique’s extractive industriesPosted in category:Long read Vincent KiezebrinkPublished on:

Vincent KiezebrinkPublished on: -

The treaty trap: The miners Published on:

Vincent KiezebrinkPosted in category:Publication

Vincent KiezebrinkPosted in category:Publication Vincent Kiezebrink

Vincent Kiezebrink