How can we make publicly funded corona vaccines accessible to all?

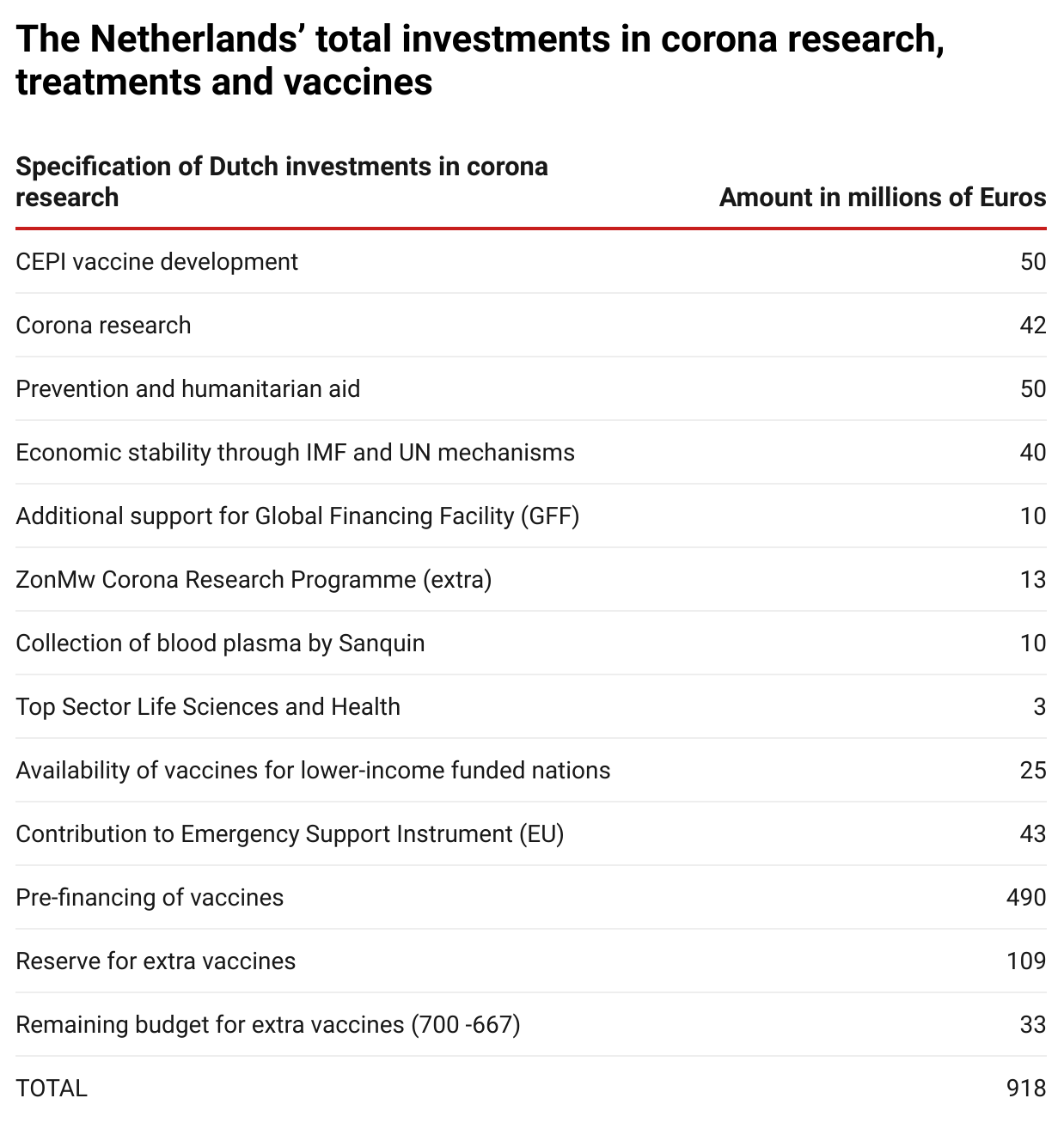

Governments worldwide have invested €93 billion in corona vaccines and medicines since the start of the pandemic. The Dutch government has invested over €917 million in corona research and vaccines since March 2020.

In view of these huge public investments, momentum is gaining for conditions to be attached to investments in drug development. The importance of this becomes clearer every day: for example, Moderna and Pfizer’s vaccines are unaffordable for at least 70 countries, despite being publicly funded. These companies have sold 96%(opens in new window) of their doses to the richest countries. This means that billions of people will not have access to a vaccine for years, which will only make the pandemic last longer for everyone. The Dutch government has been a frontrunner when it comes to setting conditions of affordability and accessibility. Also, the COVAX initiative, which aims to ensure fair and equitable access to corona vaccines on a global scale, has extensive conditions attached to its funding. What are these conditions and are they adequate to make publicly funded vaccines and medicines accessible to all?

This article provides an overview of Dutch public investment in corona research and global investments in some specific vaccines. We have analysed the conditions that should guarantee affordability and accessibility, and answer the question of whether they are sufficient. The answer is disappointing, as two case studies show. We also give recommendations on what should be done. This article was produced in cooperation with Wemos.

The Netherlands’ financial contributions to corona research

The Dutch Parliament was first informed about Dutch funding of corona research on 31 March 2020, two weeks after the start of the first lockdown. This primarily concerned urgent medical and social research. The Dutch Government made available for this purpose. In mid-April the Dutch Government(opens in new window) announced that the Netherlands would also contribute €50 million to vaccine development through the Coalition on Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI). CEPI is a foundation that collects donations to develop vaccines against emerging infectious diseases, and has now joined forces with Gavi, the Vaccines Alliance and the World Health Organization. Together, they work under the COVAX partnership to provide corona vaccines to all countries, regardless of their wealth.

The budget for domestic corona research was increased from €42 million to available for this purpose.

Dutch pre-financing of vaccine supplies

In June 2020, the Netherlands, together with Germany, France and Italy, started the Inclusive Vaccine Alliance to invest in the future supply of vaccines. The Alliance took steps to enter into an agreement with AstraZeneca to supply 300 to 400 million of their Oxford vaccine. This was soon heavily criticised as it would lead to competition between European countries and to vaccine nationalism. The negotiations for this agreement were therefore taken over by the European Commission’s Joint Negotiation Team. This team now handles all EU agreements with pharmaceutical companies, the so-called advanced purchase agreements (APAs).

The European Commission made €2.7 billion available from the Emergency Support Instrument (ESI), used to finance the future costs that manufacturers incur to be able to produce sufficient quantities of the vaccines. The member states have to pay the costs of purchasing the vaccines themselves and they will pay an additional contribution to the ESI budget mentioned above.

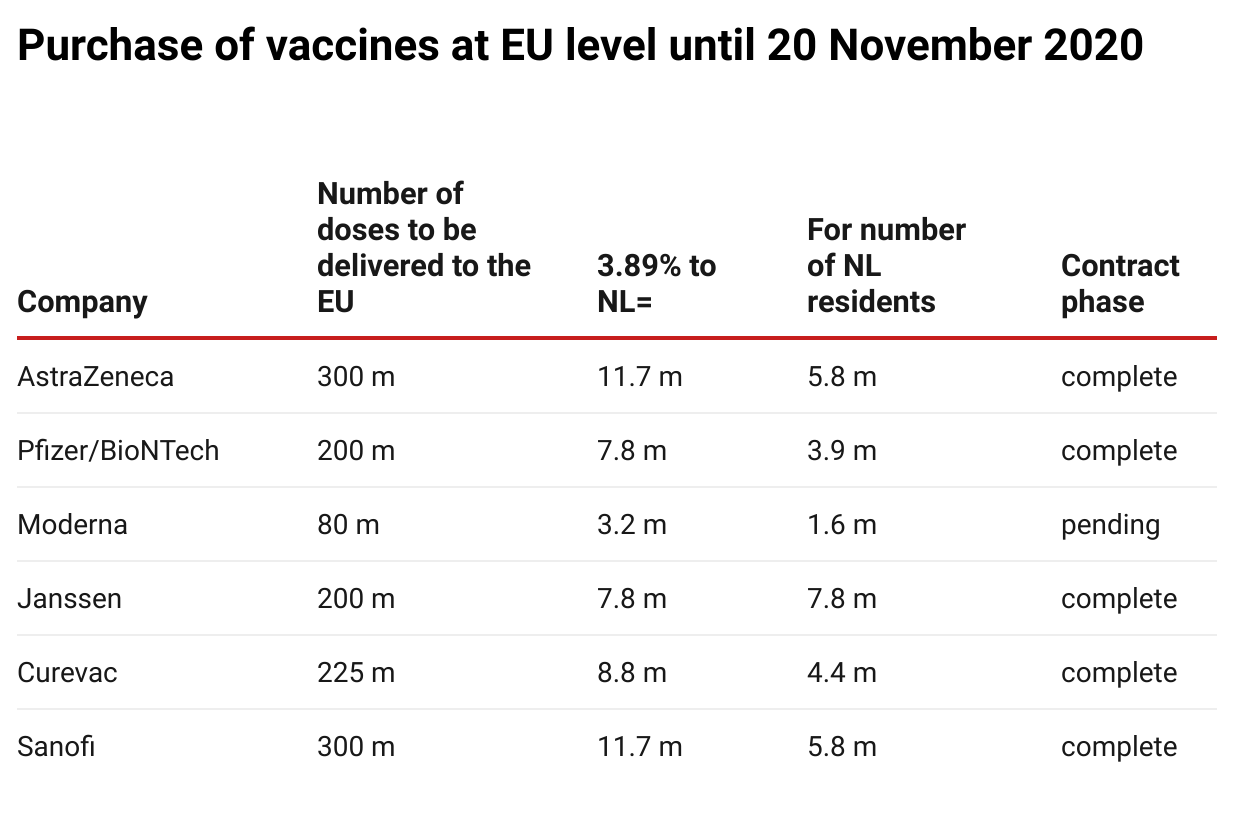

The Netherlands was entitled to purchase approximately 3.89% of all vaccines purchased in an EU context, as the distribution is proportionate to the population. The Dutch government made €700 million available for this purpose. Of this, €490 million was budgeted for the purchase of the six vaccines mentioned and €43 million for its contribution to the ESI budget.

In addition, the Netherlands had already pledged €25 million paid from this budget to COVAX to benefit vulnerable countries and an amount was also reserved for the purchase of further vaccines (€109 million). Thus, €667 million of the €700 million was already

The table above shows the situation on 20 November; meanwhile, negotiations with Valneva for the supply of 30 million doses to the EU (1.2 million for the Netherlands) and with Novavax for 100 million doses were also ongoing.

Dutch investments in research and vaccines from the start of the pandemic amount to €917 million (see table below).

The Netherlands’ conditions to guarantee accessibility and affordability

In his answer to (former) Minister Martin van Rijn of Medical Care was clear about attaching conditions to the financing of corona vaccines and therapies: “I watch over public interests such as availability and affordability of vaccines and call for attention to public guarantees where the government contributes to research”. He also stated that the Dutch government would exhibit leadership at the annual meeting of the World Health Organization and explicitly speak out about the need to share knowledge and technologies worldwide via the World Health Organization’s and that the Netherlands would actively support this.

Minister van Rijn declared that the government will only invest in the development of vaccines and medicines that will be made available to patients under acceptable conditions. Concerning the previously mentioned €42 million, the Minister expressed commitment to the principles of “Socially Responsible Licensing” (Maatschappelijk Verantwoord Licentiëren, MVL). , these principles ensure the accessibility and affordability of therapies based on patents that are developed in the public domain. With regard to the €50 million donated to CEPI for vaccine development, the Netherlands is relying on CEPI’s conditions which, , are in line with the principles of MVL. Whether the Minister’s and the government’s reliance on the conditions of MVL and CEPI was justified is discussed later in this article.

In addition to the conditions for accessibility and affordability, various Dutch institutes such as NWO, ZonMw and universities committed to conditions such as open science, open access publications and data stewardship for the funding of corona research.

Germany is another country that set conditions for its public funding. Germany’s financial support of BioNTech-Pfizer with a grant of €375 million and Curevac with €252 million was accompanied by agreements on the supply of future vaccines by the two companies to Germany. By setting these conditions, Germany negotiated accessibility for its own country, which is a limited form of accessibility and could also be called Furthermore, a UK grant to the Oxford Consortium of around negotiated supplies of the AstraZeneca-Oxford vaccine to the UK, making Europe wait longer for its agreed supplies.

Effectiveness of the principles of Socially Responsible Licensing (MVL)

the Principles for Socially Responsible Licensing

In 2019, the Dutch Federation of University Medical Centres (NFU) published the Principles for Socially Responsible Licensing that had been developed under its leadership. These principles must guarantee that licensing agreements for patents developed within university medical centres (UMCs) include clauses to achieve pricing and accessibility of medicines that is socially responsible. The principles have been worked out in a practical toolkit (the MVL Toolkit)(opens in new window)

.

The Dutch government has repeatedly referred to the MVL principles as a guarantee for accessibility and affordability. The Dutch government has also said that it would promote these principles within Europe. But the question is whether they are adequate. Therefore, we look at AbbVie as a case study where the principles were used as a guide.

Case study on AbbVie: adopting the Principles of Socially Responsible Licensing

One Dutch corona research project investigated whether an antibody could serve as a potential medicine against COVID-19. A grant of , which could be extended to €1 million. Researchers at Utrecht University, Erasmus Medical Centre and Harbour BioMed (HBM) identified an antibody that also neutralised SARS-CoV-2 infection in cultured cells. This research built on years of university research(opens in new window) that began as early as 2002. To test the efficacy in a clinical setting, a collaboration with US pharmaceutical company AbbVie was started. This is a typical example where the intellectual property, which was developed with Dutch government funding, ended up in the hands of a large international pharmaceutical company. The question is what the MVL principles achieved in this case. What availability and affordability criteria had to be met by AbbVie? Minister Hugo de Jonge, the current Dutch Minister of Medical Care, has not given a clear answer to this, but only stated that the University Medical Centres assured him that MVL principles were leading the conclusion of the licensing agreement. In addition, the Minister reiterated his commitment to ensuring that drugs co-developed with Dutch government funds would also be available in the Netherlands at an acceptable price. the MVL principles ensure this.

But what exactly are these MVL principles as currently specified in the NFU Toolkit(opens in new window) ? The NFU Toolkit should contain a provision (as an elaboration of the tenth principle) that pricing does not jeopardize accessibility. We find two clauses that refer to affordable access. The however, called Access for Humanitarian Purposes, only provides that the “licensee agrees to use Diligent Efforts to ensure effective and affordable access to Licensed Products and Processes in Developing Countries”. Thus, affordable access in this clause is limited to developing countries and does not include other patients who need the drug, for example, in the countries that have contributed financially to the development of the potential drug. Furthermore, it concerns an obligation of effort and not of a result.

The other provision in the NFU Toolkit that deals with transparency, availability and price is on page 41: “Rewarding compliance, availability, transparency and/or local development”. Remarkably, the essence of this provision is that if conditions of availability or affordability are imposed by the licensor, these will consequently mean a burden for the licensee and this should therefore be balanced by financial compensation for the licensee, to be partially paid by the licensor (!). It is suggested that financial compensation could be a reduction of the royalties to be paid. This provision thus tells us that alleged costs for the licensee associated with attaching conditions of price and availability will be partly passed on to the licensor.

It is disappointing that the inclusion of conditions regarding price and availability is optional and entirely voluntary, and that the university that does impose such conditions will be left to foot the bill itself. A more effective disincentive would be unthinkable.

In conclusion:

- In an optimal situation, the MVL principles would have led to a non-exclusive licence, to the condition that the pharmaceutical company would share knowledge and technology in the Covid-19 Technology Access Pool and to agreements on an acceptable price and accessibility of the drug to those who need it. Unfortunately, the MVL principles do not provide for any of this.

- The Dutch government’s confidence in the MVL principles to guarantee affordability and accessibility was misplaced. In truth, MVL principles actually discourage the inclusion of conditions for affordability and accessibility.

The COVID-19 technology access pool

What about the leadership that the Netherlands planned to show to make the WHO COVID-19 Technology Access Pool (C-TAP) successful? After publicly expressing active support, the government gradually made a retreat. For instance, the Netherlands repeatedly emphasised the importance of the voluntary nature of the pool.

forcing participation in C-TAP could lead to a decrease in the necessary private investments, which are important in finding a vaccine. In answers given to the Parliament, Minister van Rijn(opens in new window)

(former Minister of Medical Care) said that when private money is needed to further develop the therapy, he does not consider compulsory sharing of the patent in a patent pool “a good idea because it could deprive companies of the certainty that they will be able to recoup the costs incurred and it will inhibit private investment in therapy development, which we certainly do need”. The interests of industry resonate strongly in this cautious reasoning – and with this weak leadership, it is not surprising that no pharmaceutical company has yet shared anything in C-TAP.

Hopefully, this is about to change. Parliament has unanimously adopted

asking the government to put pressure on corona vaccine developers to share their knowledge and patents.

The effectiveness of CEPI’s conditions

COVAX explained(opens in new window)

Regarding the millions of euros that the Netherlands has donated to CEPI(opens in new window)

, the Dutch government relies on the conditions of accessibility and affordability drawn up by CEPI. Here we answer the question of what exactly these conditions are. Using another case study (Moderna), we analyse whether these conditions have been effective.

CEPI is committed to

to corona vaccines through its funding approach. CEPI is working on this with Gavi(opens in new window)

and the World Health Organization within the COVAX partnership.

aims to make two billion vaccine doses available by the end of 2021. Gavi will ensure that 92 middle and low-income countries that normally would not be able to afford corona vaccines will be able to purchase them.

CEPI must ensure that the vaccines become available and that vaccine developers commit to giving COVAX first choice in purchasing vaccines developed with CEPI funding. CEPI invests in the production capacity of the developers it supports in parallel with their early vaccine development activities.

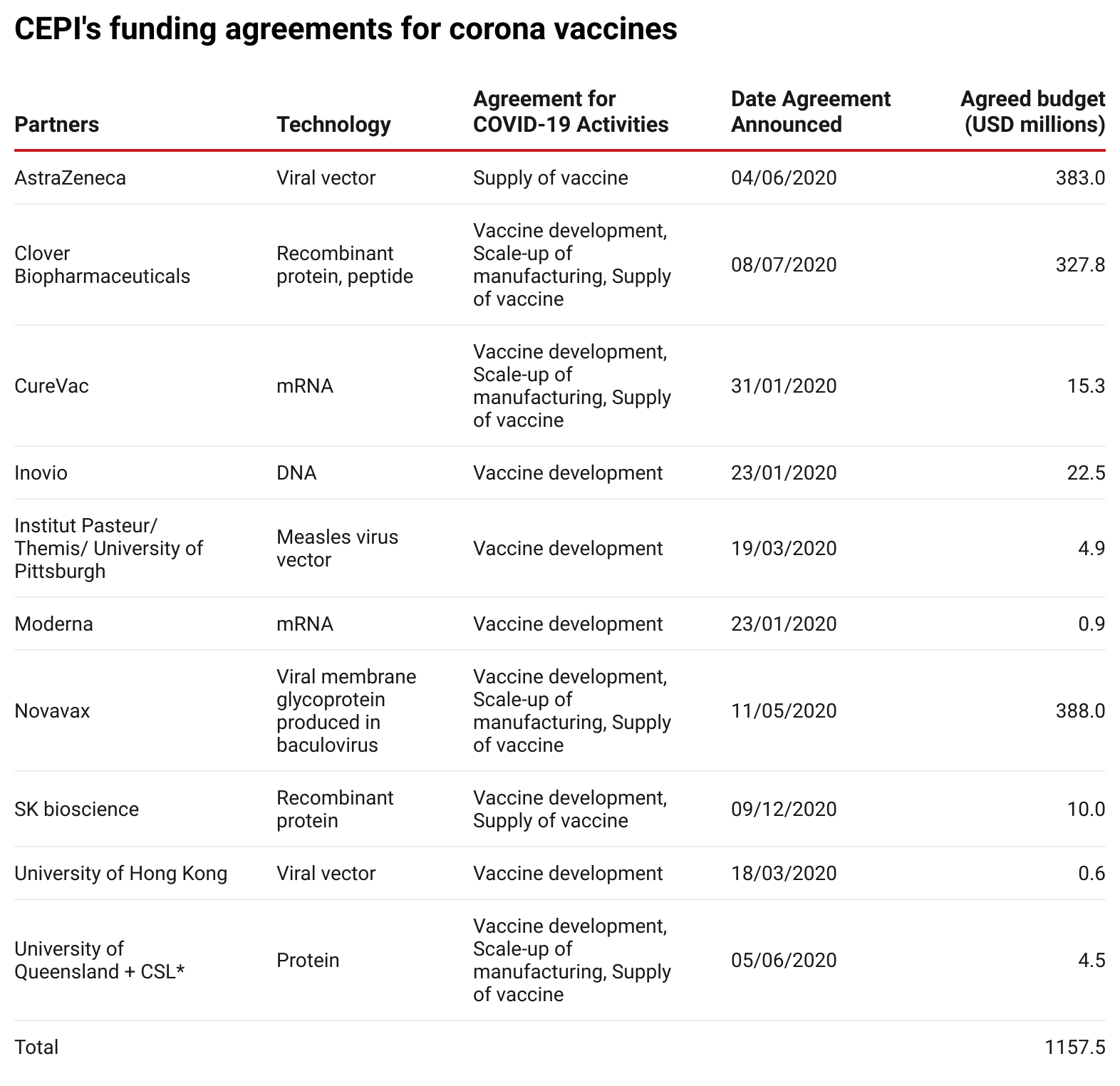

To date, CEPI has committed more than US$1.1 billion to corona vaccine research and development costs and manufacturing agreements. The table below lists all partners with whom funding agreements have been signed.

Source: Enabling Equitable Access to COVID-19 Vaccines(opens in new window)

, updated to 26 January 2021.

*On 11 December 2020, it was announced that further development had been stopped.

CEPI’s conditions

Every funding agreement that CEPA concludes sets access conditions that are in line with CEPI’s Equitable Access Policy(opens in new window) . However, depending on the outcome of negotiations with the pharmaceutical companies, the actual conditions included may differ; the agreements, unfortunately, are not public.

CEPI states the following conditions, as applied to corona:

- First, the partner must comply with CEPI’s and/or comparable commitments, including prices at levels affordable to the people who need the vaccines.

- In line with the COVID-19 Technology Access Pool (C-TAP), CEPI funding agreements include requirements for successful developers to publish and share data and materials to ensure that everyone can benefit from the work funded by CEPI.

- All production output corresponding to the CEPI-funded part of the development must first be submitted to the COVAX facility.

- Concerning delivery, the quantities to be delivered worldwide during the “pandemic period” are always indicated, as well as the share of vaccine production for middle and low-income countries in the “post-pandemic period”.

- The product must be suitable for distribution in low and middle-income countries.

- CEPI does not seek to the intellectual property developed from its partnerships. CEPI requires successful developers to manage their intellectual property in such a way that equitable access can be achieved, either by making doses available to a COVAX facility or by transferring technology to trusted partners and/or setting up production capacity in two or more countries, in order to increase production capacity.

Case study on Moderna

Using mRNA to build a protein in the human body was first explored for feasibility in 1989 by Hungarian biochemist Katalin Karikó. For more than twenty years, Karikó and her colleagues worked to ensure that the mRNA would not be broken down by the body before it could give instructions to build a protein. This important research was done at the University of Pennsylvania and was largely paid for by the US National Institute of Health (NIH) with . Two researchers, the later founders of the Moderna and BioNTech companies, went on to develop it further.

Photo: cc-by-20 Marco Verch

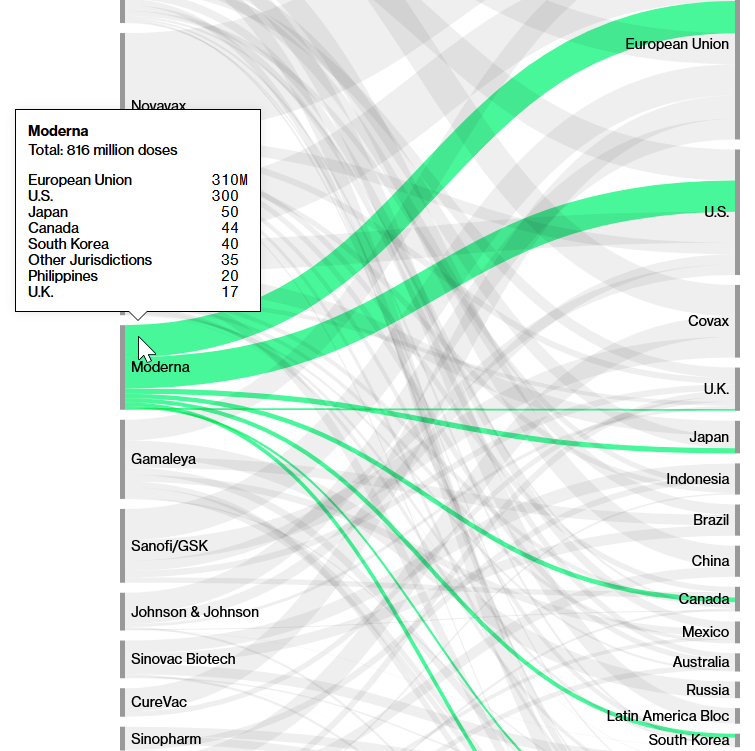

Photo: cc-by-20 Marco VerchDespite the huge government investment, it is Moderna that determines who it supplies and at what price. Moderna’s vaccine is far from accessible or affordable for middle and low-income countries. Most of its doses have been sold to rich countries (see figure below).

Number of doses of Moderna vaccine sold and their destination

Source: Screenshot of Bloomberg’s(opens in new window) Covid-19 Deals Tracker: 9.04 Billion Doses Under Contract.

The vast majority of the 816 million doses sold go to the EU, USA, Japan, Canada and South Korea. Moderna does not yet have an agreement with COVAX to supply vaccines at a discounted price as, for example, Pfizer has.

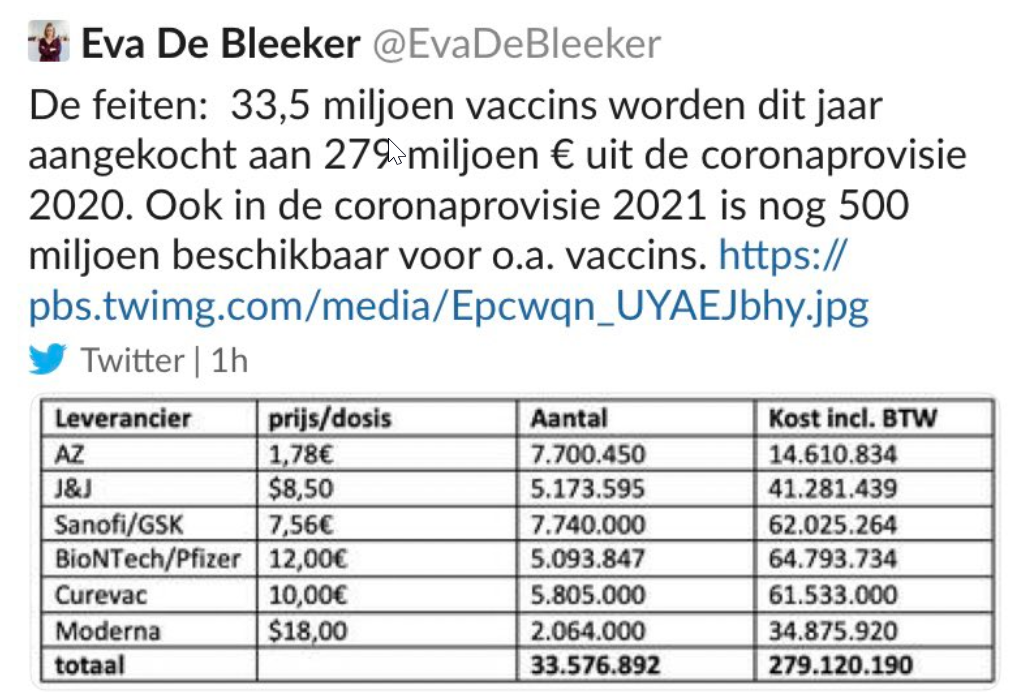

Moderna’s vaccine is the most expensive vaccine. Thanks to a tweet from Belgian politician Eva de Bleeker on vaccine prices paid by Belgium, we know that the Moderna vaccine cost them US$18 per dose.

Translation: The facts: 33.5 million vaccines purchased this year with the €279 million 2020 corona fund. The 2021 fund has another €500 million for vaccines, among others.

Conclusion:

- We can conclude that despite CEPI’s conditions, Moderna:

- Did not offer production to COVAX at a reasonable price;

- Is not supplying countries according to the principle of equitable access, but is only supplying rich countries;

- Is demanding the highest price for their vaccine;

- Has not shared knowledge and technology with C-TAP or enabled other producers to manufacture the vaccine;

- Has not been transparent about the percentage of costs paid by the US government even though they are obliged to do so.

- We can conclude at this point that neither CEPI nor the US federal government are trying to force compliance with conditions imposed on their funding.

- This also means that no guarantees concerning accessibility and affordability can be given concerning the Dutch contribution to CEPI either.

International public investments in the leading corona vaccines

A number of organisations have tried to map out the total public investment in corona vaccines and treatments. Insufficient transparency about public investments makes this difficult and therefore no overview is complete.

Based on publicly available information (through 10 January 2021), the kENUP Foundation(opens in new window) estimated that governments worldwide spent at least €93 billion on corona vaccines and treatments over an 11-month period. The vast majority of this, 93 per cent, involved a new form of investment through

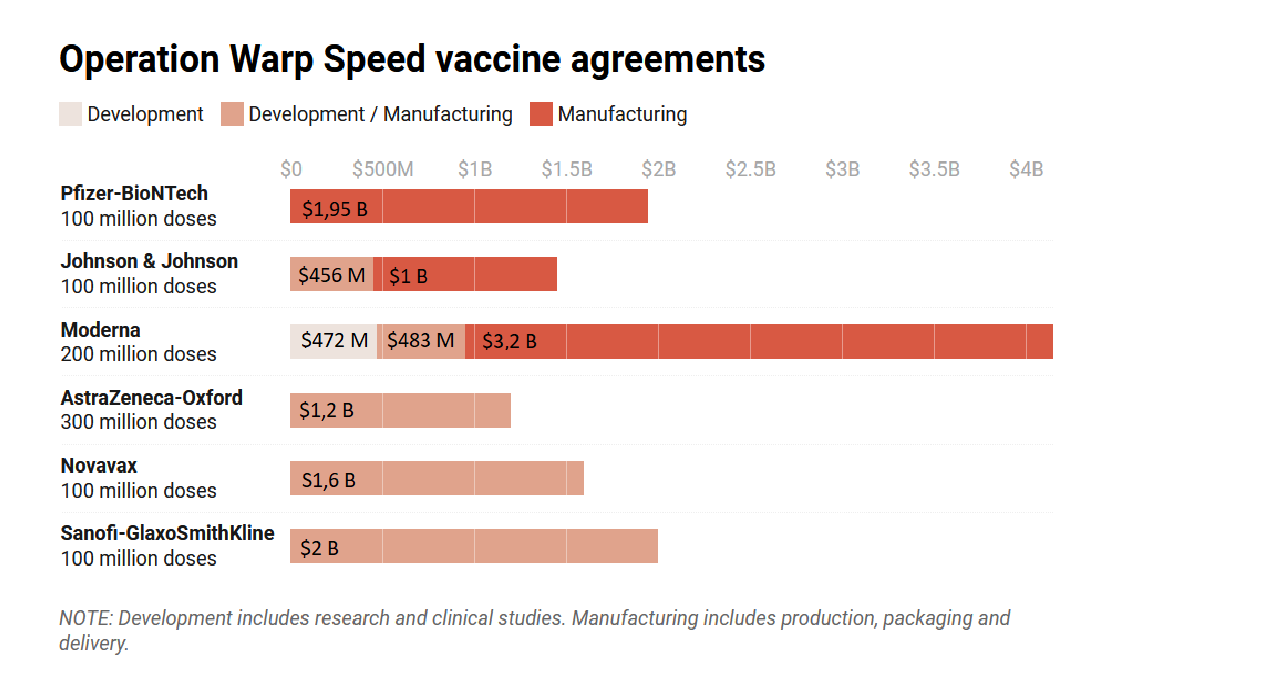

US government funding through Operation Warp Speed for vaccines in 2020

Source: Time(opens in new window)

, 14 December 2020

Source: Time(opens in new window)

, 14 December 2020

Such a purchase agreement(opens in new window) means that in exchange for the right to buy a certain number of vaccine doses within a certain timeframe, governments fund part of the start-up costs of the pharmaceutical companies. , then CEO of vaccine producer Sanofi Pasteur, said in April 2020 that billions would be needed from governments to guarantee the purchase of the vaccines because the industry cannot bear the costs alone without knowing whether there will be a market for their product.

A major objection to the APAs is that their contents are secret, despite the fact that they are government-funded. This applies to the agreements that the EU concludes with pharmaceutical companies, as well as to those of CEPI. The secrecy means that there can be no democratic control over the agreements, and thus risks a decrease in public confidence in the vaccines. NGOs working for global access to medicines have challenged this secrecy, with some success. A number of APAs entered into by the EU have now been made available by the companies. These include Curevac(opens in new window) , BioNTech and Pfizer(opens in new window) , and But important information was still redacted, such as the price to be paid, price per dose, the amount of the down payment made by the EC, the number of doses delivered per quarter, the production locations, and the liability and indemnity regime should something go wrong with the vaccine.

To the amazement of NGOs and grassroots advocates, the APAs contained perplexing and unprecedented liability clauses :

- In the event that the pharmaceutical company – as well as its affiliates, subcontractors and sublicensees and contract partners – should be held liable for damages, harm and losses arising from the use of the vaccine, they would be indemnified by the Member States.

- This indemnification covers not only the damages paid to the victim, but also legal (lawyers’ fees) and expert fees, which could be extremely expensive.

- The indemnity also covers damages suffered during the pre-clinical and clinical testing of the vaccine, whereas this is usually covered by a specific insurance policy.

- There is no time limit on this clause, which means that Member States have to pay until the final procedure has been concluded. Under certain conditions, victims have up to ten years to go to court, but the final decision could take much longer.

Due to the secrecy of the APAs, it is also impossible to determine whether there are any accessibility conditions attached to the funding, such as making doses available to COVAX or technology transfer. Furthermore, the establishment of production capacity in more countries, in order to increase production capacity, is unknown, although these would be logical conditions.

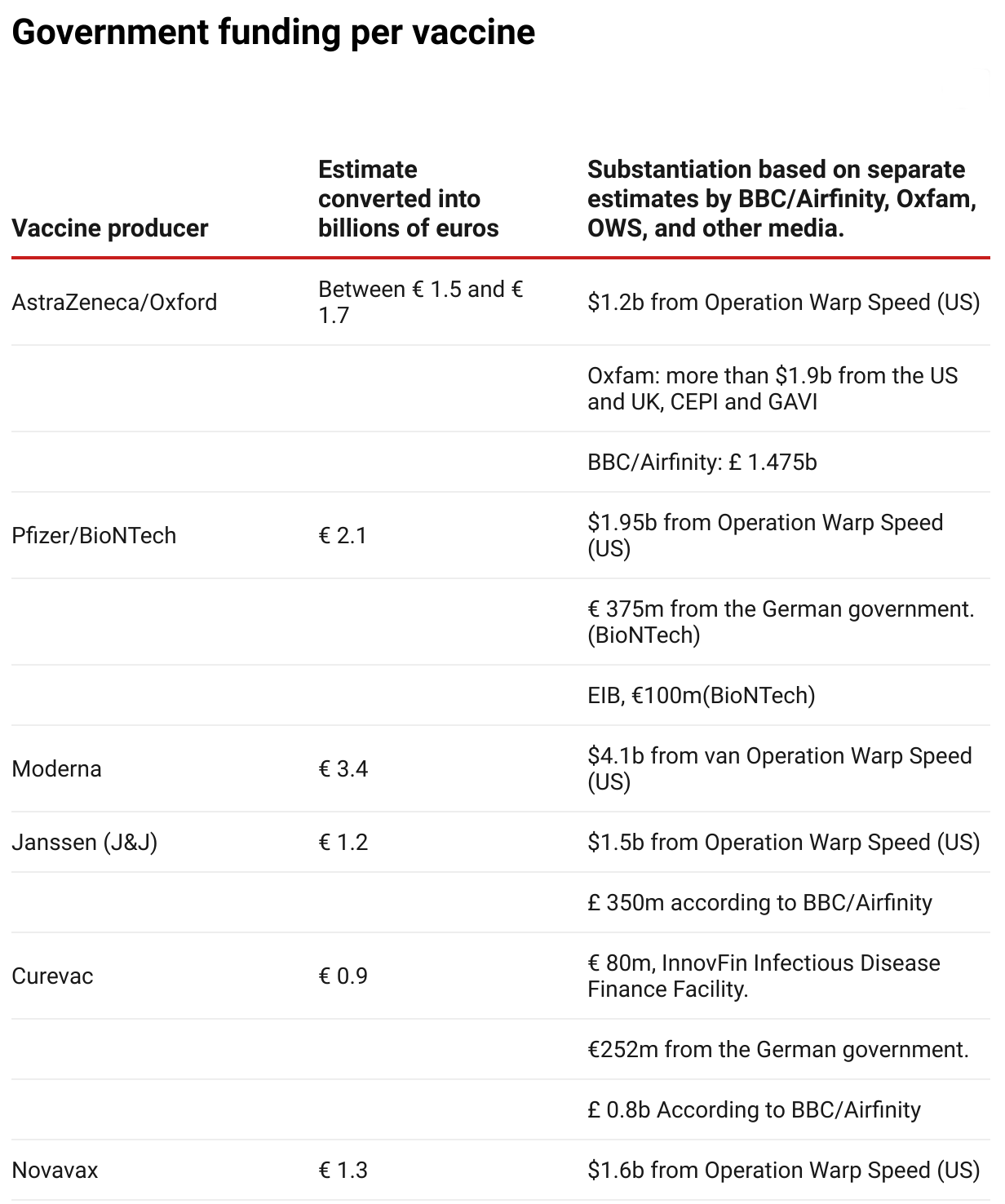

Both Oxfam and the From the , have made an estimate of the total amount of government funding per vaccine. SOMO has taken these estimates, together with data from Operation Warp Speed (OWS) and various media, to compute an estimate in billions of euros.

Photo: Source: SOMO

Photo: Source: SOMO- BBC/Airfinity(opens in new window) (£ 1= € 1,21)

- Oxfam(opens in new window) ($1 = €0,83)

- Operation Warp Speed (OWS)(opens in new window) ($1 = €0,83)

- Pfizer/BioNTech: 375 million from the German government (source: de Volkskrant)(opens in new window) . Fortune(opens in new window) stated that this is $ 445 million, but this has not been confirmed by other sources.

- Pfizer/BioNTech: 100 million from the EIB(opens in new window)

- Curevac: 80 million(opens in new window)

- Curevac: 252 million(opens in new window)

Photo: Sandra Koch CC2.0 via pixabay

Photo: Sandra Koch CC2.0 via pixabayThe question is whether government funding of these vaccines is paired with responsible behaviour by vaccine manufacturers when it comes to the availability and affordability of their vaccines. This is crucial to combating corona worldwide. The Pharmaceutical Accountability Foundation(opens in new window) has conducted research into good corona business practices; some of their findings are summarised here.

If we examine the good corona business practices of four vaccine producers in the table (Pfizer, AstraZeneca, Moderna and J&J), the most important findings are:

- Both Johnson & Johnson and AstraZeneca have pledged not to make a profit on vaccine prices for the duration of the epidemic;

- AstraZeneca has increased the global capacity to produce its vaccine. They have four agreements with manufacturers in different areas, allowing the first vaccine suppliers to reach more people in a shorter time than if AstraZeneca had remained the only producer in the world.

But if we look at the poor corona business practices of the six vaccine manufacturers in our table, we see the following:

- None of the companies currently support the WHO’s Covid-19 Technology Access Pool.

- Moderna has openly stated that it wants to earn a profit on its corona vaccine, despite the fact that it has received most public funding. This results in public funding being misused to make a profit.

- All the vaccine developers except AstraZeneca have entered into APAs which will send more than half of their expected supplies in 2020 and 2021 to high-income countries, thus limiting the supplies available to potential low and middle-income buyers.

- None of the vaccine developers have made their production costs public.

What needs to be done?

The conditions imposed on public funding of vaccine and drug development by frontrunners such as the Dutch government and CEPI have unfortunately not yet had their intended effect. It is therefore crucial that the Netherlands adjusts its instrument of Socially Responsible Licensing. Equitable access conditions should not be voluntary and negotiable, but should be included in the contracts as firm conditions. Furthermore, all contracts should be made public to enable democratic control.

In order to increase global access to corona vaccines and therapies, production capacity must be increased. This is only possible, however, through the transfer of knowledge and technology, for example, by participating in the WHO COVID-19 Technology Access Pool. This participation should be included as a condition in the procurement agreements (APAs) that governments enter into and which account for the largest share of government funding of vaccines.

Currently, pharmaceutical companies continue to adhere to a business-as-usual approach to intellectual property which limits production and supply capacity. Some countries have adapted legislation to allow compulsory licensing but this is only a domestic solution and not a global one. Another solution is a temporary waiver of patent rights to combat the corona epidemic. This proposal was submitted by India and South Africa to the TRIPS Council of the World Trade Organization (WTO) and is supported by 57 countries and more than 100 civil society organisations, including SOMO.

We have no choice. Tackling the corona pandemic must be done on a global scale – not only because it is important to show solidarity, but also because mutations will continue to develop if we do not tackle corona everywhere and expensive vaccines will no longer be effective.

Do you need more information?

-

Irene Schipper

Senior Researcher

Partners

Related news

-

EU health data law rolls out the red carpet for Big TechPosted in category:Long read

EU health data law rolls out the red carpet for Big TechPosted in category:Long read Irene SchipperPublished on:

Irene SchipperPublished on: -

Civil society coalition urges EU to put the interests of patients and citizens at the heart of the European Health Data SpacePosted in category:Published on:Statement

-