A lesson not learned 10 years after the crisis

Written by Myriam Vander Stichele

No part of the financial sector will remain unregulated! Governments and parliaments declared the end of “light touch” regulation. They promised that complex financial products won’t be traded anymore in the shadows. And last but not least; no more bank bail outs!

That was in 2008, when the devastating financial crisis caught politicians by surprise, ‘forcing’ them to bail out the banks with billions of taxpayers’ money – that same tax payer which later had to endure austerity measures and unemployment. Now in 2018, the implemented financial regulations have hardly changed the way banks, investors or speculators operate. Worse, new financial risks and financial market instability have created new crises, like a new financial crisis in Argentina and the increased divide between rich and poor.

Intense lobbying of Dutch Cabinet by corporate interests

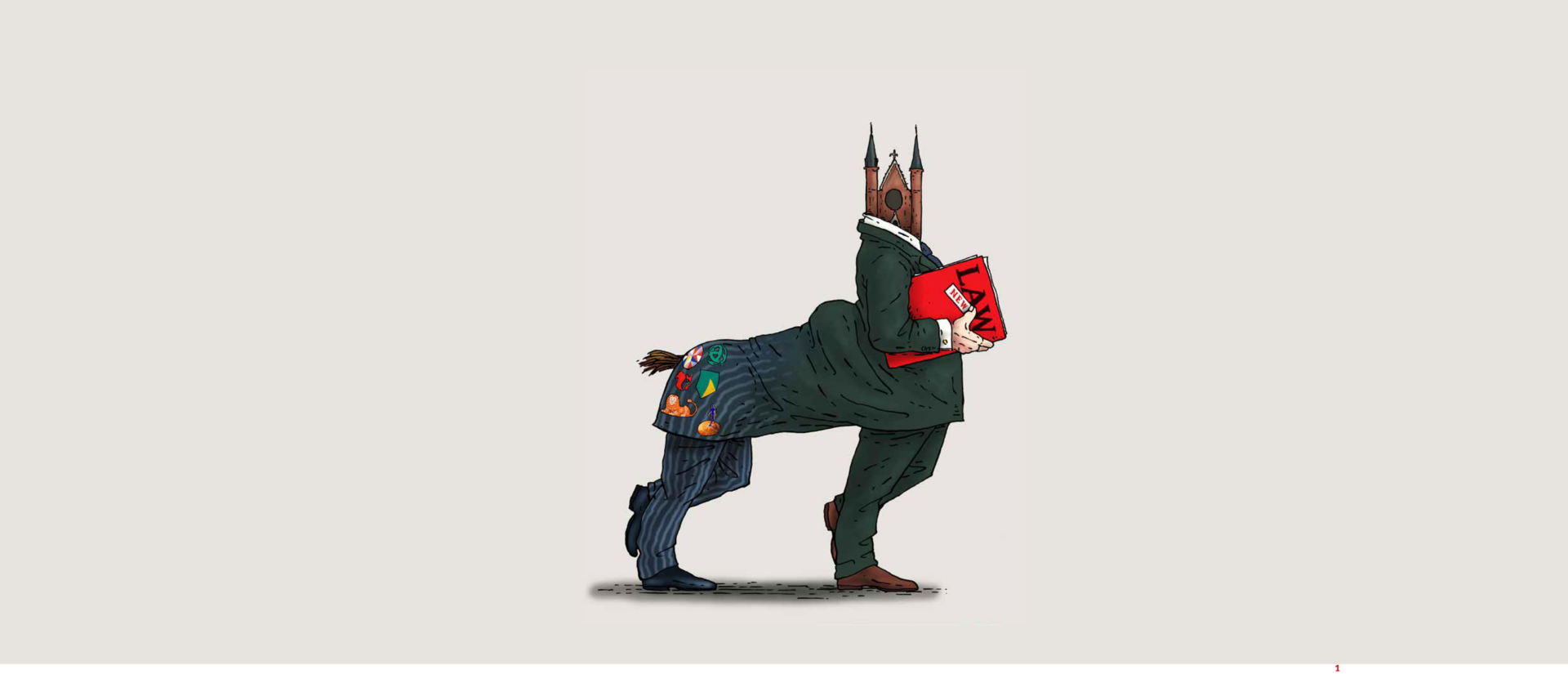

What was the blind spot? There was some recognition that the financial sector had too close links and too privileged access to financial authorities and political decision-makers while critical voices were left out. This lead to deregulation, seen as a major cause of the crisis. The lobby structures that had pushed for deregulation remained and citizen’s demands were again left in the cold.

The sprawling financial lobby got its way to create the crisis

Until 2008, the financial sector had operated a secretive and well-resourced lobby for years, which had never been shy of using hardball tactics to pursue its interests. A lobby with multiple industry associations whose tentacles reached deep into all kinds of advisory committees, public hearings and consultations – often dwarfing the voice of other stakeholders. Increasingly, “revolving doors” allowed them to exercise influence from within governments, legislative and supervisory institutions.

Stark examples of the close harmony between the authorities and the financial sector were the regular confidential meetings at the Basel Committee between governors of central banks and CEO’s of the biggest banks. Or think about the president of the European Central Bank (Draghi) and his membership of the opaque and private G30 club. Or the chief negotiator of the European Commission making a phone call to lobbyists from the confidential negotiating room during trade treaty negotiations on financial services.

This lobby machine reinforced the neoliberal policies of financial authorities and decision makers. The financial sector was pretty much left to govern itself. With only minimal supervision, it was allowed to continue to outsmart and financialise economies and societies. Almost no one bothered for the inclusion of other stakeholders such as labour movement, academia, society and public interest groups.

As a result, laws and rules were lacking to prevent a crisis and no supervisory mechanism was in place to intervene when a worldwide financial crisis struck:

- banks had become ‘too big to fail’ and too interconnected;

- complex financial innovations were unchecked and left to boom and bust, including the sub-prime mortgages that triggered the financial crises;

- capital flowed freely around the world as a result of numerous (trade) treaties, allowing the effects of the crisis to spread more rapidly;

- special speculative strategies involving risky derivatives, allowed food prices to rise leading to food riots;

- money and profits increasingly moved to non-transparent tax havens leaving the public budgets with too little money to cope with the crisis.

Too big to beat

In the aftermath of the financial crisis, civil society organisations called for a different financial system – one that doesn’t create social and environmental problems for societies. They also proposed practical solutions for the problems created by the financial lobby:

- split the banks;

- create a diverse and democratically governed financial system (e.g. cooperatives, public banks.) to serve the public interest;

- stop speculative capital flashing around the world by imposing a financial transaction tax (FTT), capital controls and a ban on tax dodging;

- prevent any financial speculation on food and other commodity prices;

- regulate to serve the public interest with citizens input and ban unbalanced, non-transparent access to public authorities by the financial sector.

‘The public’ showed their support for these reforms as they were angry about effects of the crisis and frustrated they could not be involved in the post-crisis reforms. Some civil society organisations actively campaigned, lobbied and even participated in official consultations to advocate for reform. Finance Watch, a ‘public interest association dedicated to making finance work for the good of society’, was established with the support of European parliamentarians to counteract the financial sector lobby.

The politics of quantitative easing

But, in the end, governments, parliamentarians, financial authorities and civil servants all allowed the financial sector to continue its relentless lobbying practices. Reformers simply lacked the expertise and necessary information, which they got from the financial sector. Decision makers were afraid to apply restrictions on an industry that they had been told was too essential for the economy. The result was that they got biased information and abandoned civil society demands as the following examples reveal:

- A legislative proposal to split the banks between basic banking and speculative divisions was delayed until 2014 by huge relentless lobbying efforts that undermined the efforts of a high-level expert committee (Liikanen report). The watered-down EU’s Bank Structural Reform Regulation law was further doomed as a result of French and German government efforts to weaken the law as they bowed to bank lobby pressure. The regulation was ultimately never adopted a majority of European parliamentarians opposed stricter regulation.

- Proposals for an alternative banking system that would be more diverse and would serve the interests of civil society were never placed on the agenda of the Group of Experts on Banking Institutions (GEBI), an EC committee to advise on banking reforms. All but two of its members worked for the banks whose interests they promoted. The bankers used leaked draft legislative texts while the non-bankers in the GEBI had even no preparatory papers. After the GEBI was criticised by civil society for its unbalanced membership, it was closed rather than recomposed.

- Civil society organisations used a variety of means to limit, by law, financial food price speculation. Despite their active participation in public consultations, campaigns and the introduction of concrete amendments, the draft law was markedly weakened. Versatile intervention of lobbyists secured the inclusion of their interests until the last minute of the legislative process and thereafter, during the elaboration of the technical standards.

- group of EU countries initially agreed to introduce a financial transaction tax (FTT) for which many citizens had campaigned for years, even decades. However, only one year after the financial industry began lobbying against this tax, the proposal ended up severely diluted and was eventually opposed by one of the initially pro-FTT countries. French President Macron has more recently argued against the FTT to try to lure bankers to Paris on the back of Brexit anxieties.

- Civil society revelations about abusive lobbying practices led to a few non-legally binding improvements in transparency of lobbying in EU institutions. Meanwhile, the Dutch government steadfastly refused to make lobby activities more transparency, despite the fact that this lack of transparency clearly benefitted Dutch banks at the expense of the people (see this SOMO report). Dutch banks have neither felt an obligation to increase lobbying transparency nor taken sufficient responsibility for lobby groups they are a member of.

Finance cannot change without democracy

Civil society, journalists and researchers can put pressure on politicians and financial authorities by exposing links between lobbyist practices and political decision-making and thus forcing them to regulate the financial sector in a more equitable manner. Consumers can demand that banks stop lobbying against their interests by transferring their financial resources to other banks that promote social and environmental objectives.

Developing, promoting and engaging in alternative banking practices and refusing speculative investments can form the basis for regulations that prohibit unsustainable financial practices. An example of this is the EU’s efforts to encourage financing activities that mitigate climate change. The European Parliamentary elections in May 2019 will serve as a prime opportunity for citizens to demand that parliamentarians commit to prioritising society’s interests with regard to the financial sector.

On this ten-year anniversary of the crisis, we should remember this essential blind spot, the way how financial legislators and authorities allowed for the financial sector to have its interests incorporated in the financial reforms. Governments, parliaments, regulators and supervisors must unambiguously prioritise the interests of the citizenry, through a more transparent and democratic decision-making process in support of alternatives that serve people and planet.

Do you need more information?

-

Myriam Vander Stichele

Senior Researcher

Related news

-

Why share buybacks are bad for the planet and peoplePosted in category:Opinion

Myriam Vander StichelePublished on:

Myriam Vander StichelePublished on: Myriam Vander Stichele

Myriam Vander Stichele -

The trillion-dollar threat of climate change profiteersPosted in category:Long read

The trillion-dollar threat of climate change profiteersPosted in category:Long read Myriam Vander StichelePublished on:

Myriam Vander StichelePublished on: -

The treaty trap: The miners Published on:

Vincent KiezebrinkPosted in category:Publication

Vincent KiezebrinkPosted in category:Publication Vincent Kiezebrink

Vincent Kiezebrink