Regulation to reduce CO2 emissions is the most effective way to address climate change

Myth: “Pricing carbon is the most efficient way to make polluters pay”

SOMO’s ‘Facing the facts: carbon offsets unmasked’ series debunks eight myths promoted by the offset industry.

Carbon market proponents claim:

Proponents claim that corporations have not had incentives to include pollution in their cost-profit analyses and, therefore, no incentive to reduce their emissions. They argue that putting a price on carbon can make polluters – especially the biggest ones – pay for their pollution. If well-designed, the argument goes, carbon pricing systems -such as offsets- can create strong economic incentives for more climate-friendly activities. In order to accomplish this, pollution (such as carbon emissions) needs to be treated as a measurable unit that can be priced.

Reality check:

The extraction and burning of fossil fuels drive the climate crisis, not the lack of a price tag on carbon. The idea that pricing carbon will address the climate crisis is based on several fallacies and misconceptions, the most prominent of which we address below:

1. Paying for carbon credits is not the same as paying for the climate impacts of GHG emissions.

In theory, a ‘price signal’ means that companies and customers see the full cost of a good or service, including the cost of any pollution created. The assumption is that if companies and customers see the full costs reflected in a price, this will impact their behaviour. However, this seldom happens, and companies regularly externalise pollution costs to society. For example, if a company pollutes a river, even if the company is fined, which is far from common, the actual cost to society can include things like loss of fishing livelihoods and increased demand for health care (these costs are often referred to as ‘externalities’).

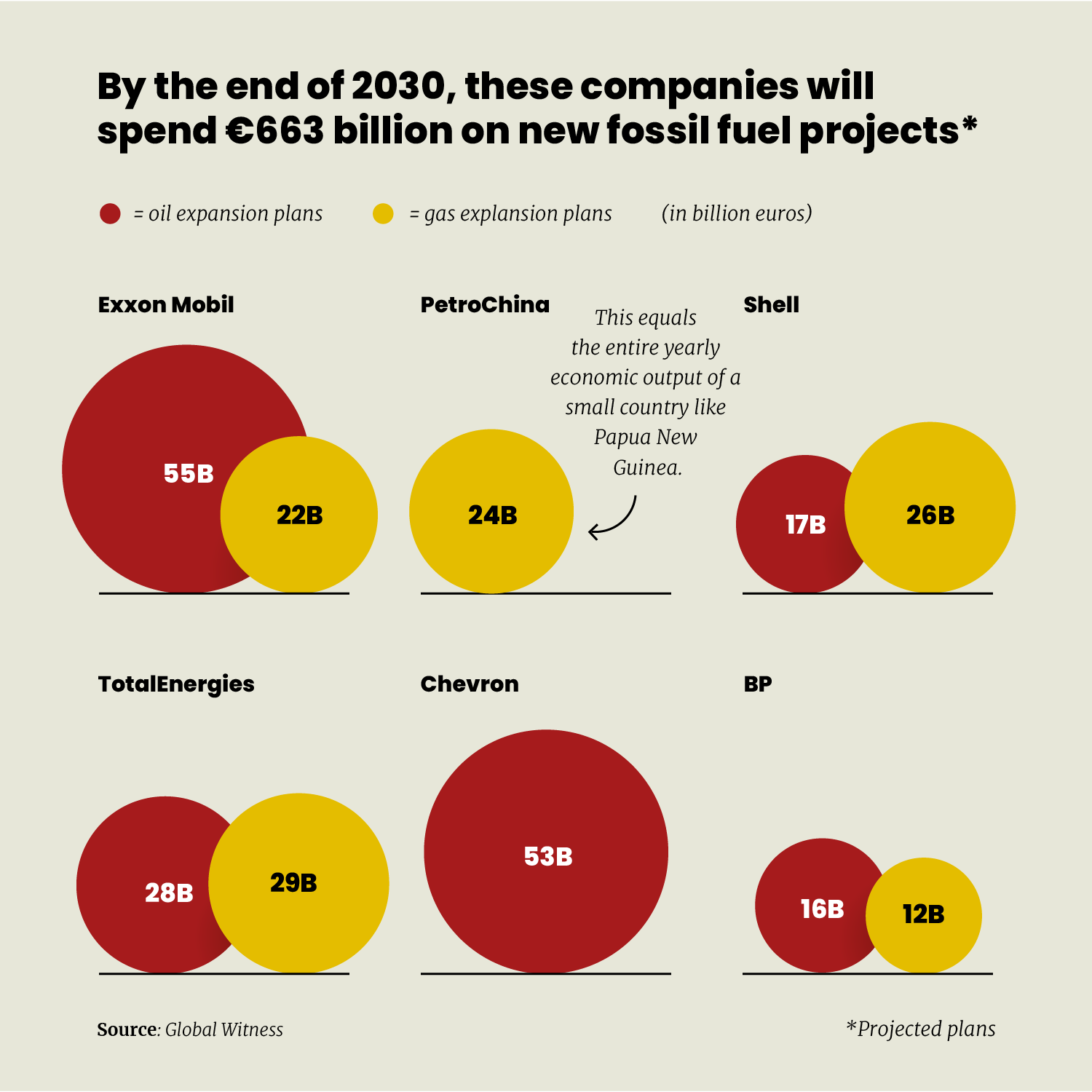

With climate change, the costs to society include massive loss of life, damage to the health and safety of tens of millions of people, devastated livelihoods, and homes and ecosystems destroyed. Some of these impacts can be given a market value, but many cannot. Carbon credits do not even attempt to put a price on the climate impacts of a company’s extraction, burning or use of fossil fuels. They put a price on carbon molecules. The average prices(opens in new window) for carbon credits in the voluntary carbon market have fluctuated between $4.04 and $7.37 per credit over the last three years. As of October 2024(opens in new window) , the prices of land-based carbon credits in the voluntary market have dropped to a mere $0.32. The “price” companies pay for credits is nowhere near the social, environmental and human costs of their carbon emissions in the present, let alone their decades of past pollution. The price of carbon credits is insignificant compared to the massive profits these companies make and has also not deterred major oil and gas companies from pursuing new fossil fuel extraction plans.

2. Carbon pricing is a perversion of the “polluter pays” principle.

This principle was originally meant to ensure that polluters would pay for the costs associated with their pollution. However, the principle has been distorted by corporate lobbyists to mean “the polluter can pay to pollute.” Instead of being mandated to pay fines and reparations that are commensurate with the impact of their pollution, carbon prices allow corporations to pay “fees” for carbon credits. Rather than being held legally responsible for climate damages, polluters have created a permissive context for ongoing and expanded ‘legitimate’ emissions. Moreover, the money from the sale of carbon credits largely benefits the carbon offset industry, mostly based in the Global North, instead of addressing the impacts of climate pollution.

3. Pricing schemes turn carbon into a business cost; when costs increase, they are usually passed on to customers.

The idea that if companies have to pay for their pollution, the pollution will stop has been shown to be flawed(opens in new window) . The costs, such as buying carbon credits, can simply be passed along to customers. Research by the environmental organisation CE Delft(opens in new window) exposed a particularly egregious example: under the EU Emissions Trading Scheme, carbon permits, which had a monetary value, were given for free to the steel, iron and refinery sectors. These industries, despite having not paid for the permits, passed the putative costs on to consumers. The research suggests this led to windfall profits of €14 billion between 2005 and 2008, implying “a substantial transfer of money from consumers to the energy-intensive industry.”

Pricing carbon is not the most efficient way to achieve emissions reductions

Policymakers often understand ‘efficiency’ to mean that carbon offsets are achieving the best emissions reductions at the lowest cost. However, myriad exposés have shown offsets frequently do not represent actual emissions avoided, removed or reduced. Phantom credits, over-estimates of carbon reductions, and other serious problems, have been documented by scientists, the media and civil society.

Moreover, carbon offsets are an ineffective and unjust means of allocating resources. Most of the money involved in the offset industry is flowing between companies involved in the sector. For example, investors and brokers take an estimated one-third(opens in new window) of the money raised by carbon credits. A sprawling side industry, including carbon quality rating firms, data providers, carbon footprinting firms, and many others, has emerged. All of them make money. What is left for implementing the carbon offset projects and supporting the affected communities is only a small fraction of the money circulating in the system.

There is no basis to claim that carbon offsets efficiently address climate change or reduce emissions… so why does this fallacy persist? Perhaps because it is a very effective way to preserve the economic status quo and help fossil fuel-based industries to continue making short-term profits at the cost of people and the climate.

Carbon pricing is replicating policy failures

The first major “pollution market” was not, in fact, a carbon market but a sulphur dioxide (SO2) trading scheme(opens in new window) set up as part of the US Clean Act Amendment in 1990. The argument, however, was the same: the market would make it cheaper to reduce SO2 emissions. In this case, polluters did not actually pay for the permits; permits were handed out for free and functioned essentially like subsidies. In fact, companies received so many permits that they could store them for years and keep polluting. The European Union(opens in new window) , Japan(opens in new window) and China(opens in new window) , in contrast, directly regulated factories to reduce SO2 in the same period. These countries(opens in new window) had visibly more effective results and reached reduction targets much more swiftly than the US. Yet, somehow, the failed US trading scheme became the model for global climate policy. How was that possible?

The answer lies in the US’s geopolitical influence. At the first UN climate agreement, negotiated in Kyoto in 1997, most nation-states were sceptical about including a trading scheme for carbon that had failed in the US for SO2. However, the US delegation, led by then Vice President Al Gore(opens in new window) , insisted on creating a carbon market(opens in new window) and even threatened to pull out of negotiations if carbon trading was not accepted. Other countries buckled under US pressure. The US decided to pull out of the Kyoto Protocol in 2001 after the trading language was already embedded in the text.

Meanwhile, European corporations began to see the financial opportunity that carbon trading could mean for their business, as well as its capacity to prevent or undermine(opens in new window) other types of regulation in the region. They organised into lobbying(opens in new window) coalitions with direct access to the European Commission. This paved the way for the creation of the EU Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS), which was hailed as the most cost-efficient way to decarbonise the EU economy. However, following in the footsteps of the US SO2 trading scheme, corporations received their pollution permits for free in the initial phases of the ETS. They were able to trade these, which generated windfall profits for some of the biggest polluters in Europe(opens in new window) . Here, too, the system was plagued(opens in new window) by a large amount of “excess credits” that companies could hoard for years while avoiding action to meaningfully reduce their emissions.

Despite historical precedents and the lack of any credible underpinning to suggest that ‘carbon pricing’ effectively addresses corporate contributions to climate change, the concept persists. This is largely due to the sustained lobbying by companies of policymakers. Ideology has overshadowed evidence in the policymaking processes worldwide.

In a nutshell

The notion that carbon pricing or credits can help address climate change is unfounded. Carbon credits do not put a price on the climate impacts of extraction, burning or use of fossil fuels. They put a price on carbon molecules so that they can be traded. This has created a system in which industries are allowed to “pay to pollute” and maintain business as usual. Yet history shows that the most effective way to address pollution is for governments to enforce strict regulations that require industries to reduce their emissions.

What’s the alternative? Read more about how to think outside the ‘offset box’ at the end of this series.

More from the blog series

-

A brief history of colonialism, climate change and carbon marketsPosted in category:Long read

Joanna CabelloPublished on:

Joanna CabelloPublished on: -

To achieve real emission reductions, carbon offsetting needs to endPosted in category:Long read

Joanna CabelloPublished on:

Joanna CabelloPublished on: -

Carbon offsets are an obstacle to real climate solutionsPosted in category:Long read

Ilona HartliefPublished on:

Ilona HartliefPublished on: -

Carbon offsets are diverting money away from climate action in the Global SouthPosted in category:Long read

Ilona HartliefPublished on:

Ilona HartliefPublished on: -

The offset industry, riddled with conflicts of interest, is not fixablePosted in category:Long read

Ilona HartliefPublished on:

Ilona HartliefPublished on: -

Carbon offsets often disenfranchise communitiesPosted in category:Long read

Joanna CabelloPublished on:

Joanna CabelloPublished on: -

-

Scaling up carbon markets means scaling up emissions and abusePosted in category:Long read

Joanna CabelloPublished on:

Joanna CabelloPublished on:

Do you need more information?

-

Joanna Cabello

Senior Researcher -

Ilona Hartlief

Researcher