The offset industry, riddled with conflicts of interest, is not fixable

Myth: “Flaws in carbon offsetting can be fixed”

SOMO’s ‘Facing the facts: carbon offsets unmasked’ series debunks eight myths promoted by the offset industry.

Carbon market proponents claim:

When confronted with scientific research, NGO investigations, and media reports exposing serious failures across multiple offset projects, the industry has often argued that the cases represent just a few ‘bad apples’. Proponents also argue that improved methodologies and safeguards can address any real problems identified. They claim that the offset industry can guarantee high-quality credits. In other words, the industry argues that the problems that have been exposed are limited in scope and that they are fixable.

Reality check:

The carbon offset problems are systemic, not exceptional

The problems identified with the carbon offset industry by academic, media and civil society research cannot reasonably be described as a few ‘bad apples.’ Many of the investigations looked at the offset system, not just individual cases. For example, an investigation by The Guardian, Die Zeit and Source Material(opens in new window) found that more than 90% of forest-based carbon offsets certified by Verra were worthless. A major research initiative by the Berkeley Carbon Trading Project(opens in new window) , which assessed the quality of Verra’s four most-used forest-based (REDD+ ) crediting methodologies, exposed how the system has enabled project developers to claim far more carbon credits than they can justify with actual reductions. Additionally, in the past two years, a slew of reports(opens in new window) and investigations(opens in new window) have exposed human rights abuses, land grabbing(opens in new window) and conflicts(opens in new window) linked to carbon offset projects.

Responding to these exposés by focusing narrowly on things that it can appear to ‘fix’ (such as methodologies, safeguards, and guidelines), the industry has provided itself and its customers with a tool for endless obfuscation and dissembling. The reality is that the core problems of the offset industry are not fixable. First, the industry is based on a set of assumptions that do not match scientific reality. Second, the offset industry is riddled with serious conflicts of interest, which are inherent to the system. Both points are explained further below.

Voluntary standards and safeguards to avoid criticism

The main standard-setting body in the voluntary carbon market , Verra, has consistently published revised(opens in new window) methodologies(opens in new window) and safeguards over the years and has repeatedly used this ongoing development process as a shield when addressing criticism.

Furthermore, the Integrity Council for the Voluntary Carbon Market (ICVCM) was launched(opens in new window) “to set and maintain a global standard for high integrity in the voluntary carbon market.” It is a multistakeholder initiative (MSI) heavily driven by investor interests, including(opens in new window) the biggest fossil fuel and financial actors, and replicates the MSI approach that has largely failed on other issues because the different levels of power between and amongst civil society, industry and government are never properly acknowledged.

Carbon trading schemes rely on false equivalences

To create a carbon market, it was necessary to turn emissions (greenhouse gas molecules) into a fungible, tradable commodity. In doing so, companies and proponents have had to conflate different gases, geographies, biological processes, sociological contexts, and timelines in ways that do not stand up to scrutiny. False equivalences have been hard-wired into carbon trading schemes and are at the core of this market’s logic. Below are examples of some of these false equivalences:

- Fossil vs Biotic carbon: Scientists(opens in new window)

distinguish between fossil carbon and biotic carbon. It is not legitimate to equate(opens in new window)

fossil carbon, stored deep in the earth for millennia (until it is extracted and burned), with biotic carbon, such as that stored in trees, which has always had a natural life cycle. Firstly, the burning of fossil fuels cannot be reversed. It will stay there for millennia once it is released above the ground. Secondly, fossil carbon is always much more concentrated than biotic carbon because it was produced by millions of years of heat and pressure. Therefore, it is next to impossible for the biotic carbon cycle to absorb(opens in new window)

all the concentrated fossil carbons that are burned – no matter how many forests, swamps and other ecosystems are protected or tree plantations expanded.

- Temporality: Offsets do not remove carbon in the same time frame or at the same speed at which it is released by burning fossil fuels. For example, carbon removed by trees is calculated over the lifetime of the tree; it can take decades for a tree to fully absorb all the carbon calculated by the offset project, up to 100 years in some cases. Yet offsets are often used to compensate for emissions that were released in hours or days (for example, a flight). In other words, the emissions that were supposedly compensated will already impact the climate now, while the theoretically ‘equivalent’ reductions of the ‘offset’ project will only materialise later (if at all, given the near impossibility of guaranteeing the future. (See Myth 1).

- Greenhouse gases: All seven greenhouse gases (GHG) identified in the Kyoto Protocol have been equated to carbon dioxide so that they can be made tradable commodities. Yet, each gas is different, and their theoretical equivalences have led to accounting(opens in new window) failures(opens in new window) . Take methane and CO2(opens in new window) , for example, the two largest greenhouse gases within the Kyoto Protocol accounting system. Both are tradeable as ‘CO2-equivalent’ (CO2e) units. Methane, however, stays in the air for 12 years, whereas CO2 stays in the air for hundreds of years. Making these gases equivalently tradeable is shifting even greater burdens onto future generations.

Carbon offsetting is an industry riddled with conflicts of interest

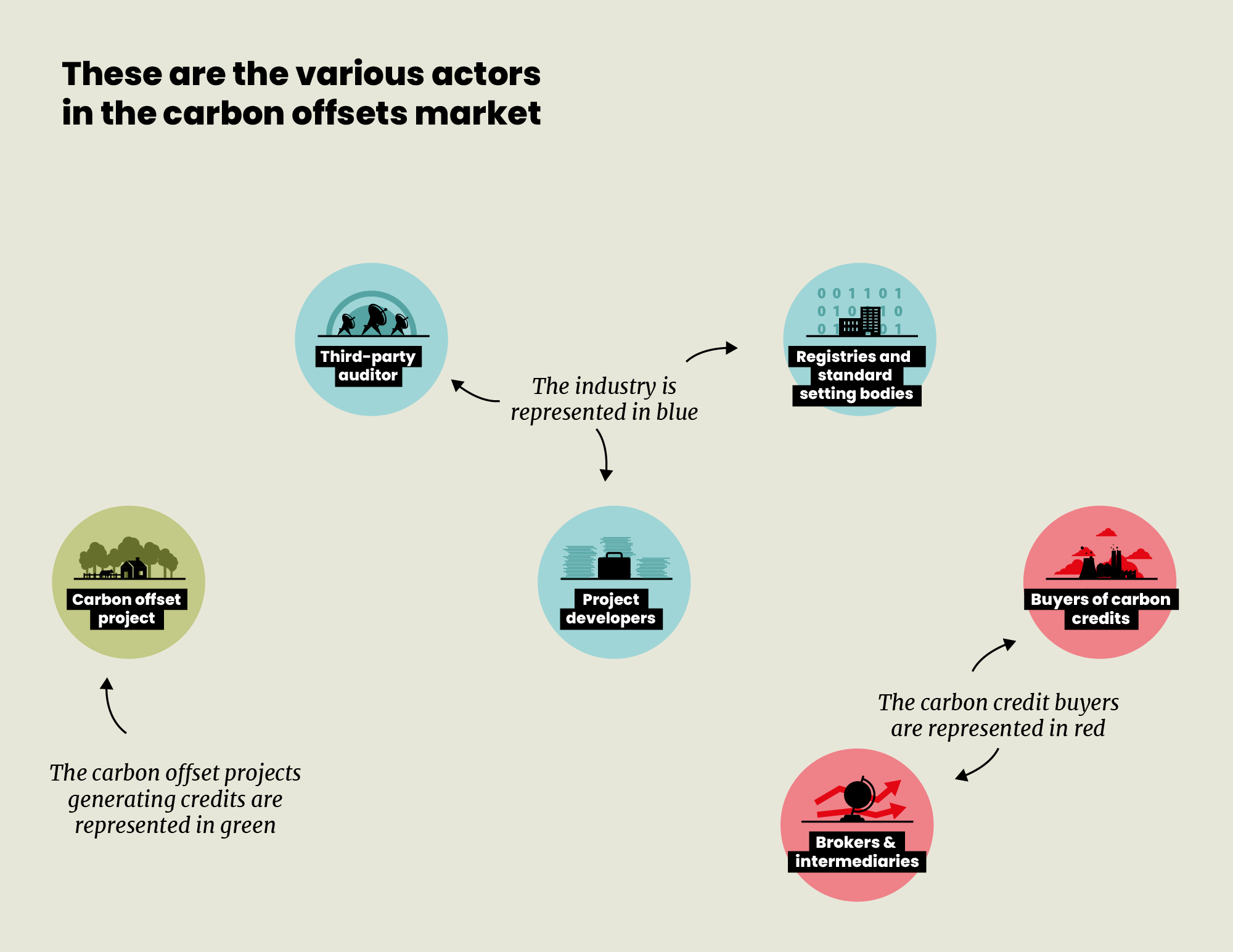

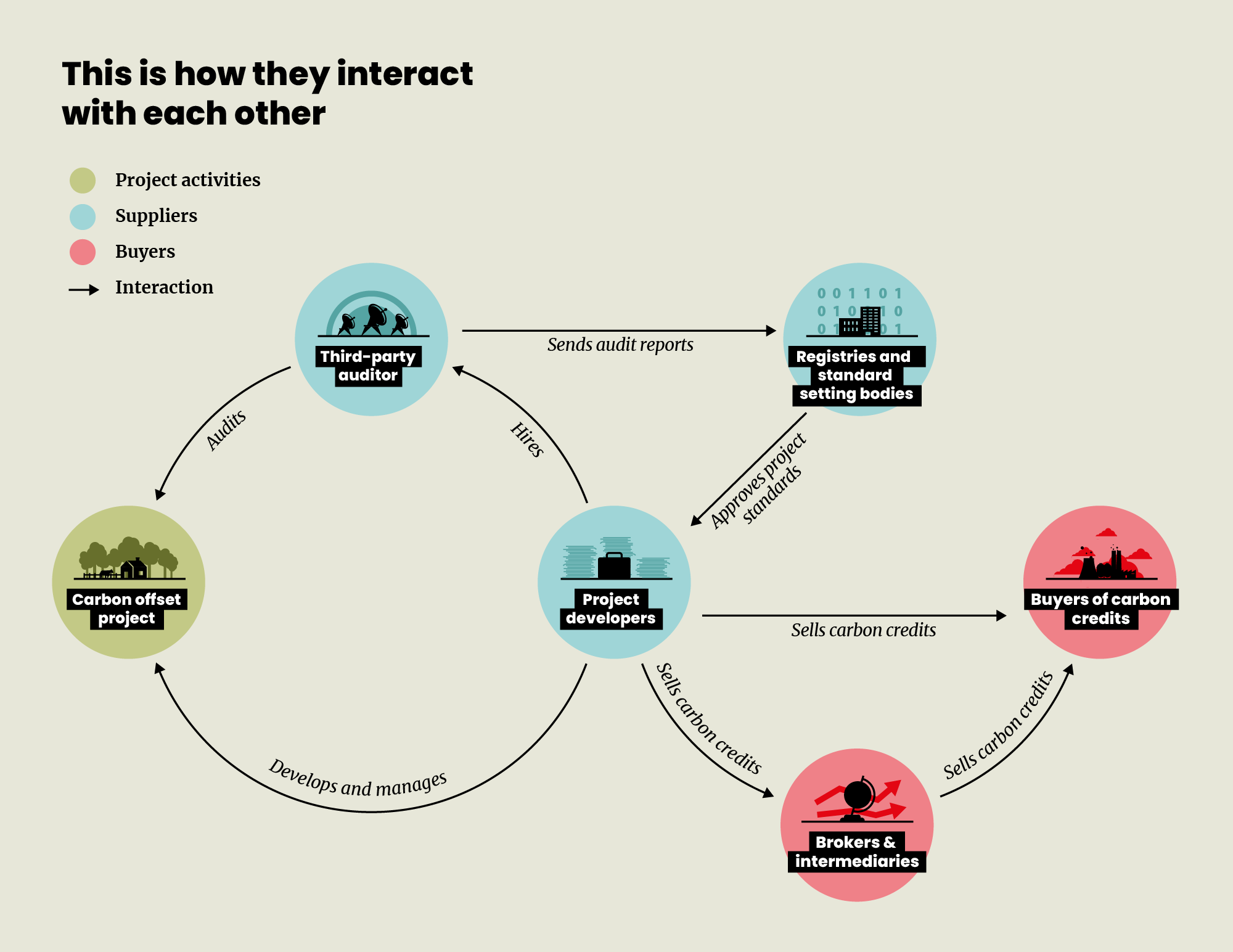

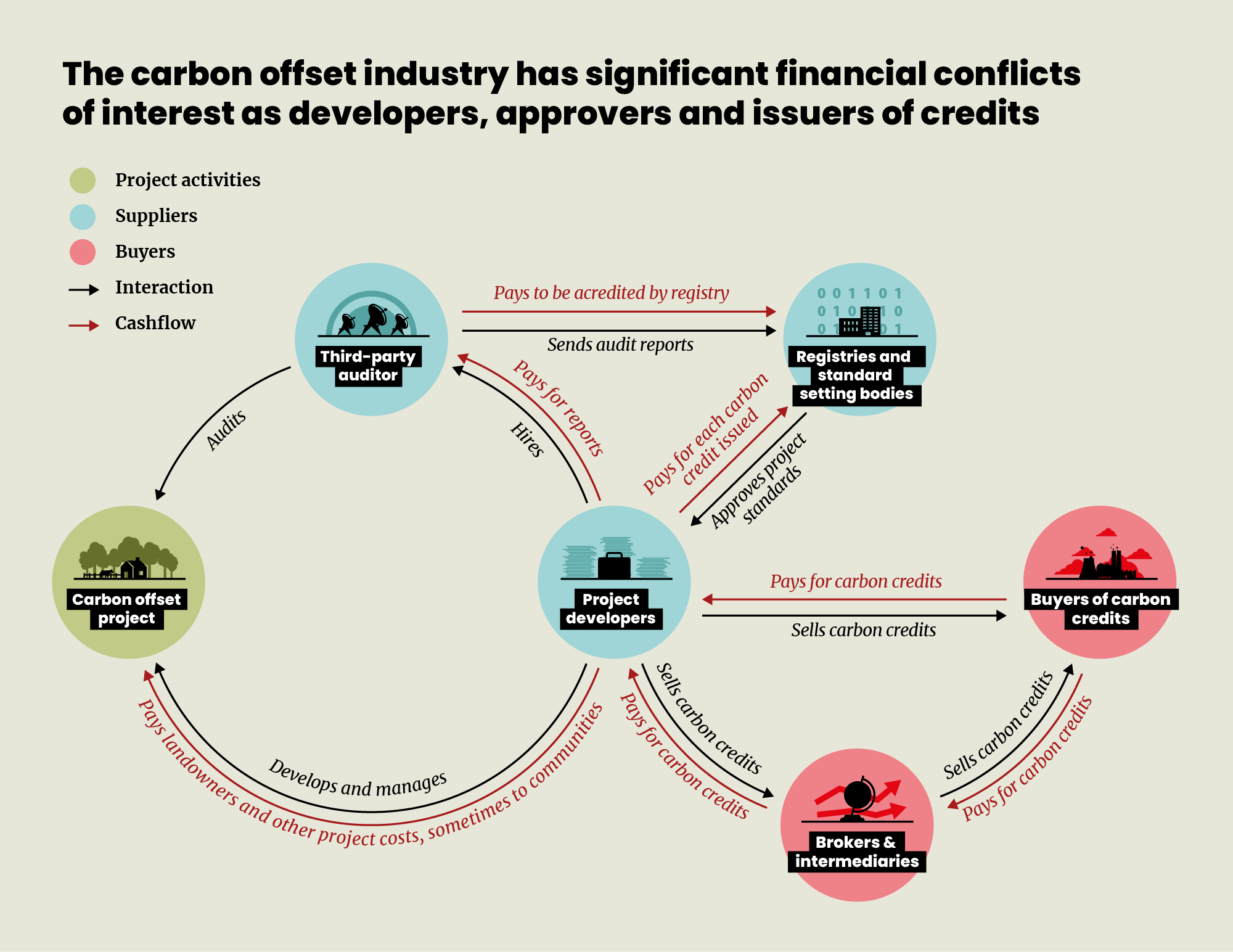

The carbon offset industry involves a range of actors, including project developers (who develop and manage projects), standard-setting and registry bodies (who establish the standards and safeguards and oversee the system), third-party auditors (who audit projects for validation and verification approval) and carbon credit buyers (usually corporations). A key problem in this industry lies in the nature of the relationships and incentives among the actors involved.

Firstly, there is substantial financial dependency between the actors who set the standards and oversee the system, the actors who monitor the compliance of projects with the standards, and the project developers themselves. There are several standard-setting bodies in the voluntary carbon market , with US-based Verra being the most prominent for forest-based offset projects. Under Verra, project developers can only generate and sell credits if their project is validated and verified as compliant with Verra’s standards. But Verra can only exist and bring in revenue if carbon credits are issued. The vast majority of Verra’s $32 million in revenue in 2022(opens in new window) , for example, came from what is called ‘issuance levies’ – the amount Verra charges project developers per verified carbon unit (VCUs). The more VCUs it issues, the more income it receives. Similarly, Gold Standard, another major standard-setting body, earned $11 million of its $17 million total income in 2023(opens in new window) from issuance levies.

These standard-setting bodies have set themselves up as overseers, but they also have commercial dependence on the actors they oversee (the project developers). Meanwhile, the auditing firms must be registered by Verra (and pay a fee to Verra for this), and they are then hired and paid for by the project developer. Consequently, there is a client relationship with the entity they assess. Auditors need to keep Verra and project developers happy, or they do not have a job.

Secondly, everyone involved in the offset industry has a vested interest in inflating the amount of the commodity to be sold (carbon credits). Suppose a carbon offset project can make 100 credits or 1,000, depending on how rigorous it is with its accounting methodologies. In that case, there is an incentive to apply carbon accounting methodologies in ways that make more credits. Given the dependencies between the various actors, there is also the means and opportunity for creative accounting. This is not a theoretical concern. On the contrary, research(opens in new window) has repeatedly exposed how carbon offset projects, audited by supposedly independent auditors and verified by Verra, have massively exaggerated the amount of carbon emissions they reduce.

New methodologies are mere veneers

The industry’s response to the avalanche of exposés of problems has been to claim that updated methodologies or processes can address any issues. Yet, none of these addresses the problems set out above. Moreover, some of the proposed new methodologies for improving carbon accounting schemes have been criticised by independent actors, from academia(opens in new window) to carbon rating firms(opens in new window) . For example, while reviewing Verra’s 2023 methodology and standard updates, the Berkeley Carbon Trading Project concluded that the changes do not tackle the underlying problems, because the problems are “not from written requirements themselves but from their poor implementation by developers and poor verification by auditors in practice.”

In a nutshell

New methodologies cannot and do not address the core problems of the carbon offset market. They do not resolve the false equivalences that are hard-wired into the very DNA of the carbon offset industry, nor do they resolve the conflicts of interest in how projects are verified. What focusing on new methodologies does do is buy the industry more time. It’s a great (and profitable) technique: keep working on the methodologies and standards to distract attention from the fundamental problems. But those problems, and the consequences, remain.

What’s the alternative? Read more about how to think outside the ‘offset box’ at the end of this series.

More from the blog series

-

A brief history of colonialism, climate change and carbon marketsPosted in category:Long read

Joanna CabelloPublished on:

Joanna CabelloPublished on: -

To achieve real emission reductions, carbon offsetting needs to endPosted in category:Long read

Joanna CabelloPublished on:

Joanna CabelloPublished on: -

Carbon offsets are an obstacle to real climate solutionsPosted in category:Long read

Ilona HartliefPublished on:

Ilona HartliefPublished on: -

Carbon offsets are diverting money away from climate action in the Global SouthPosted in category:Long read

Ilona HartliefPublished on:

Ilona HartliefPublished on: -

Regulation to reduce CO2 emissions is the most effective way to address climate changePosted in category:Long read

Joanna CabelloPublished on:

Joanna CabelloPublished on: -

Carbon offsets often disenfranchise communitiesPosted in category:Long read

Joanna CabelloPublished on:

Joanna CabelloPublished on: -

Climate leadership means reducing real emissionsPosted in category:Long read

Audrey GaughranPublished on:

Audrey GaughranPublished on: -

-

Scaling up carbon markets means scaling up emissions and abusePosted in category:Long read

Joanna CabelloPublished on:

Joanna CabelloPublished on:

Do you need more information?

-

Joanna Cabello

Senior Researcher -

Ilona Hartlief

Researcher