Shell’s AGM: back to fossil fuel business as usual

How Shell and its shareholders sacrifice the energy transition

The oil industry is no longer trying to fake concern about climate change. At the Shell 2023 AGM on 23 May new CEO, Wael Sawan, and the Board made clear that renewable energy is not profitable enough to increase value for the shareholders. They blatantly stated that oil and gas are better investments. The pursuit of shareholder value is one of the most significant obstacles to addressing climate change.

Shell’s 2023 AGM made the news because it was interrupted by climate protestors. Outside of the financial press, far less attention was paid to the shareholder value issue, the impact of which was on this occasion, sadly, far greater.

Well ahead of the AGM, Reuters(opens in new window) reported in February that Shell’s CEO openly hinted at reversing the company’s climate strategy, doing so against the backdrop of a 10% rise in BP’s share value after that oil major announced a reduction in its climate ambitions. He has since reduced the numbers of executive vice-presidents responsible for renewables and energy solutions and has withdrawn from some climate friendly projects.

Rather than keeping a commitment to let oil production fall by 1-2% a year, Shell’s current management insisted at the AGM that fossil fuels are again the core focus of its business and investments since renewables are not profitable enough. According(opens in new window) to Sawan “cutting oil and gas production is not healthy” as demand remains high and “Shell is a great company and we’re changing to ensure we become a great investment too”.

Shareholder value vs. the planet

Shell has long focused on delivering big returns to shareholders, through dividends and share buybacks. When a company re-purchases its own shares to drive up the value of the shares on the stock market and the income per share, the remaining shares become more attractive. In 2022 alone, Shell paid(opens in new window) almost US$ 26 billion to its shareholders: US$ 7.4 billion in dividends and more than double (US$ 18.4 billion) in share buybacks. It finished an additional US$ 4 billion share buyback programme(opens in new window) in April 2023.

Notwithstanding the billions returned to shareholders, the value of the shares is not high enough according to Sawan. He is concerned that the total value of Shell’s shares traded on the stock exchanges (called “market capitalisation”) is almost half of that of its US rivals Exxon and Chevron(opens in new window) . This lowers Shell’s competitiveness to cheaply invest in oil and gas, according to Shell’s Chair.

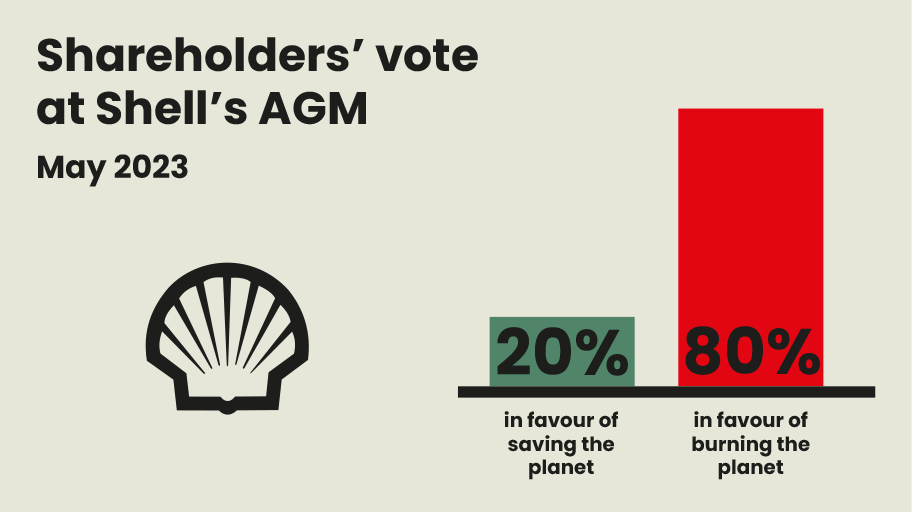

Resolution 26

Activist pro-climate shareholders called on the company to speed up its energy transition plans by supporting Resolution 26 at this year’s Shell AGM. Shell’s Board vehemently advised against the resolution, stating(opens in new window) that the Shell “board does not consider Resolution 26 to be in the best interests of the company, its shareholders as a whole, our customers, and the climate”.

Eighty percent of shareholders followed Shell’s recommendation. And an even higher number gave approval for Shell to continue repurchasing up to 10% of Shell’s shares into 2024. The voting outcome will influence Shell’s new energy transition strategy, to be announced on 14 June 2023 at Shell’s “capital day”, from which we can expect a higher focus on oil and gas. Shareholders will have to approve the new energy transition strategy at the 2024 AGM. They would so agree with Shell’s intent, stated at the AGM, to disobey the 2021 Dutch court order to reduce Shell’s emissions by 45% by 2030 as compared to 2019.

Puppet masters or passives?

So, who are the shareholders whom Shell wants to please by focusing on fossil fuels and what is their rationale for voting as they do? It is important to remember that very few shareholders are individual people. Around 63% of Shell’s shareholders are estimated to be institutional investors. The largest institutional investor is the US asset management firm, BlackRock, which is also the largest asset manager in the world. By mid-April 2023, Blackrock held 10.6% of Shell’s publicly traded . The second largest investor, and the world’s second largest asset manager, is Vanguard, which holds 3.41 % of the outstanding Shell . As the major shareholders they have often significant influence on corporate strategies. A “growing number of major investors” had reportedly(opens in new window) pressed Shell to focus on higher financial returns “rather than energy transition plans”. It is not disclosed – at the time of writing – if BlackRock or Vanguard are among them or how they voted on 26.

However, most asset managers and other institutional or retail investors own less than 1% of the shares of the many listed companies worldwide in which they invest: this is a standard strategy to reduce the risk of financial losses. These investors seldom do their own scrutiny and due diligence when it comes to AGM proposals, many preferring to rely on advisory firms instead. The proxy vote advisory business is dominated(opens in new window) by two firms: the Institutional Shareholder Services (ISS) and Glass Lewis. Both firms advised(opens in new window) their clients to vote against Resolution 26. The much smaller UK based advisor, Pensions & Investment Research Consultants, recommended(opens in new window) voting against the Shell 2022 energy transition report and against re-appointment of the chair of the board, due to “heightened climate-related financial risks” for shareholders.

Another way in which shareholders passively acquiesce in planet-damaging corporate strategies is due to investment funds, including those managed by BlackRock and Vanguard, that combine shares of many companies. The value of their index funds simply track the value of the shares on the stock market. Those investing in such funds hardly consider the strategy of the companies in whose shares the fund invests, nor are they informed how the fund managers vote on their behalf (“proxy voting”). BlackRock also manages Shell’s shares for pension funds and smaller institutional investors, who often do not scrutinise how their asset manager is voting.

In turn, BlackRock also satisfies its own shareholders by returning $4.9 billion to its shareholders in 2022, including $1.9 billion in share buybacks. And the largest shareholders(opens in new window) of BlackRock are … Vanguard (9%) and BlackRock (7%). BlackRock recommended(opens in new window) to its own shareholders to vote against three resolutions on social and climate sustainability.

The bottom line

The system is one of exceptional deniability and lack of responsibility. The oil companies, asset managers and proxy advisory firms, as well as other institutional investors and financiers, have no legal obligation to plan or make financial provisions for the energy transition. They are part of an out-of-control competition on financial markets to maximise shareholder value in the short term. This dangerous dynamic squanders billions dollars, euros, etc. in dividends and share buybacks rather than energy transition investments. It saddles societies globally, and especially the poorest, with the increasing costs of climate chaos, and with financial devastation in the long term.

Politicians must now surely realise that without legal limits on fossil fuel investment and rules governing things like dividends and share buybacks, the fossil fuel industry will remain a huge impediment to keeping global warming to 1.5 degrees. Sadly, policymakers are being bamboozled into giving oil companies and investors (more) subsidies to deal with energy transition, using public money to help massive multinationals to keep ensuring high shareholder value.

Do you need more information?

-

Myriam Vander Stichele

Senior Researcher

Related content

-

How much of Shell’s 2022 record profits will be registered in tax havens? Probably quite a lot.Posted in category:News

How much of Shell’s 2022 record profits will be registered in tax havens? Probably quite a lot.Posted in category:News Jasper van TeeffelenPublished on:

Jasper van TeeffelenPublished on: -

The Shell climate verdict: a major win for mandatory due diligence and corporate accountabilityPosted in category:Opinion

Joseph Wilde-RamsingPublished on:

Joseph Wilde-RamsingPublished on: Joseph Wilde-Ramsing

Joseph Wilde-Ramsing -

Quick profits, lasting damagesPosted in category:Opinion

Ilona HartliefPublished on:

Ilona HartliefPublished on: Ilona Hartlief

Ilona Hartlief -

Shell’s legal weapon to threaten a just energy futurePosted in category:Opinion

Bart-Jaap VerbeekPublished on:

Bart-Jaap VerbeekPublished on: Bart-Jaap Verbeek

Bart-Jaap Verbeek -

Shell incapable of meaningful role in energy transitionPosted in category:News

Shell incapable of meaningful role in energy transitionPosted in category:News Ilona HartliefPublished on:

Ilona HartliefPublished on: -

Still playing the Shell Game Published on:

Ilona HartliefPosted in category:Publication

Ilona HartliefPosted in category:Publication Ilona Hartlief

Ilona Hartlief

-

New UK legal case on Niger Delta oil spills – a litmus test for justice in the energy transitionPosted in category:Opinion

Audrey GaughranPublished on:

Audrey GaughranPublished on: Audrey Gaughran

Audrey Gaughran -

Climate finance as a business modelPosted in category:Long readChris Kaspar de PloegPublished on:

Climate finance as a business modelPosted in category:Long readChris Kaspar de PloegPublished on: -

COP27: EU adoption of a “modernised” Energy Charter Treaty would open door to more climate chaosPosted in category:Opinion

Bart-Jaap VerbeekPublished on:

Bart-Jaap VerbeekPublished on: Bart-Jaap Verbeek

Bart-Jaap Verbeek