Leathermen of Pakistan

The sad story behind our leather shoes, clothing and accessories

Do you know where your shoes come from? Or that fancy leather jacket? There’s a good chance they’re from Pakistan because it’s the world’s biggest leather producer. Unfortunately, there’s nothing fancy about the labour conditions for leather workers in Pakistan. Read more here Hell-bent for leather.

Workers often toil for long hours and low wages in deplorable conditions. They struggle with health issues because they work with toxic substances and unsafe heavy machinery, often without adequate protective equipment. SOMO, NOWCommunities(opens in new window) and Oxfam(opens in new window) decided to carry out research into Pakistan’s leather industry. NOOR photographer Asim Rafiqui(opens in new window) documented some of the working conditions in the tanneries of Karachi. You can read the story of the leathermen of Pakistan here.

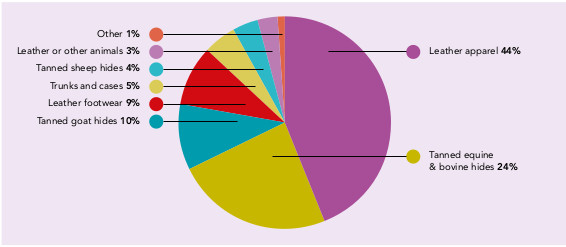

Pakistan produces around 4,500 tonnes(opens in new window) of leather a year. Almost half of this leather ends up in Europe, much of it as manufactured products such as shoes, garments, suitcases and other accessories.

In the leather company

Most Pakistani leather companies are based in Sialkot, Lahore and Karachi. There are many ‘integrated’ factories, where hides are tanned, dyed and processed into garments. The hides that are used come from cows, buffalo, goats and sheep.

From skin to leather

The animal hides are transformed into leather in the so-called ‘wet-blue’ process. Large wooden drums are filled with water and the chemical chromium, a salt compound from the metal chrome. These drums spin for a period of two to 24 hours. The workers often have no shoes or protective equipment in a very wet and extremely hot environment full of toxic chromium gases. This causes respiratory illnesses and nasty skin infections.

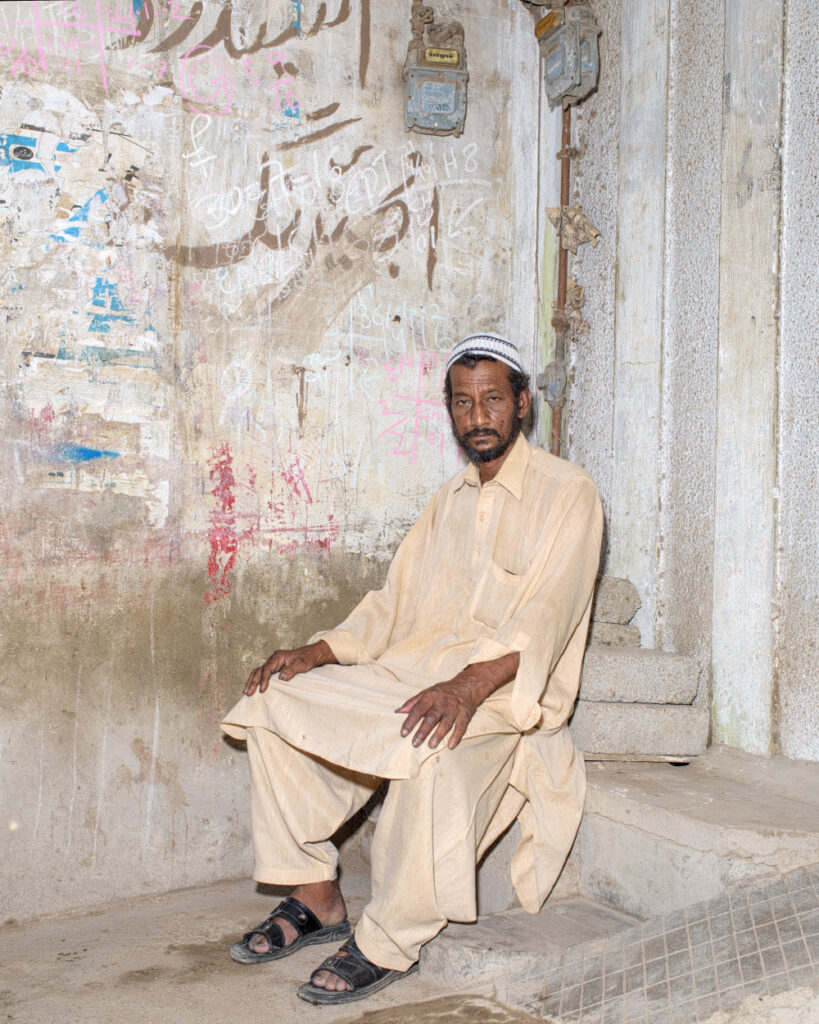

Muhammad’s story

Muhammad suffered from acute kidney failure that started 14 years ago. At the time, he was working with a ‘hot-toggle’ machine in the tannery, in an extremely hot environment. He was suffering from constant dehydration because of it. He has been on dialysis to keep him alive ever since his kidneys failed. Meanwhile, he has continued to work in the same factory although he has been moved to a less strenuous workstation. He has not received any compensation for his illness, and has been forced to schedule his dialysis outside working hours. If his dialysis treatment interferes with his working hours, he says, his employer will dock his pay.

Rinse, dry and stretch

When the hides come out of the drums, they are wet and blue, hence the name ‘wet-blue’. The hides are drained, rinsed and dried and, in some cases, stretched. Then they are prepared for the dying process. Before the hides are ‘shaved’ in a machine to even out the thickness. Our research revealed that these machines are insufficiently protected in one third of the companies. Interviewed workers told us that colleagues have lost their hands or arms working with these machines.

Under Pakistani law, employers are obliged to provide protective equipment for people working with chromium. Through surveys and in-depth interviews with tannery workers in Karachi, it became clear that simple protective gear such as gloves and masks are often not being provided. Workers are also not aware of the need to use these, nor are they sufficiently trained to use the heavy machinery. Machines do not have proper safety protection measures in place and the stress to comply with production quotas leads to accidents where workers lose hands and arms.

Painting and processing

The hides are painted and oiled to lubricate the leather. The leather is then dried, which results in a tradeable, intermediate product called ‘crust leather’. A proportion of this crust leather is ready to be exported. The other leather will be processed in Pakistan and turned into end products. To turn the leather into garments, it goes through a process of ‘dry finishing’ in which the appearance and properties for end use are improved. This can involve the application of a surface coat, and mechanical processes like polishing, dedusting and flattening.

https://youtu.be/zZ337bfaGNg(opens in new window)

Insufficient wages and long working hours

As well as facing dangerous and unhealthy working conditions, workers often have trouble making ends meet. Their salaries are far below the cost of living: 14,000 Rupees (the legally allowed minimum) or less a month (€119). This is not enough to buy three meals a day, let alone to rent a house or feed a family. The Asia Floor Wage campaign(opens in new window) , an international coalition of unions, calculates that the minimum monthly living wage in Pakistan for 2015 was 31,197 Rupees (€278.42). The inability to pay their rent, food and medical costs forces some of the factory workers to repeatedly take out loans with their employers. This only causes deeper problems. Sometimes workers have to ask their children to start working so the family can pay off their debts.

Mohammad: “I need at least 40.000 to 50.00 Rupees to run my expenses. I am only able to cover my expenses because my daughters and wife work. My three young kids study but also have to go to work.”

The factories use a quota system where workers are paid their regular daily hours if they manage to meet their quota. However, the quotas are constantly set higher. Workers are now required to work longer hours and more quickly. They often work without taking any breaks to go to the bathroom or to drink water.

Precarious work

A large proportion of the workers in the leather companies are not hired by the companies. In our research, we found that 95 per cent of workers are hired through labour contractors. This makes them very vulnerable. Often they do not have a legal contract binding them to the factory they work in. They are forced to work unpaid overtime. If they complain, they are sacked. If they join a union, before they know it they are moved to more difficult working stations.

https://youtu.be/oyJxhbrCDQA(opens in new window)

How can the European Union help?

The European Union (EU) has made a special trade agreement with Pakistan (and some other developing countries) that provides trade tariff reductions (GSP+)(opens in new window) on the condition that Pakistan implements core international conventions relating to human and labour rights. However, the EU doesn’t sufficiently check if these conditions are being met. There is a huge opportunity here to help Pakistan’s leather workers! The EU should urgently improve its monitoring.

What else can be done?

The Government of Pakistan should implement and enforce both existing national laws, as well as the international human and labour rights conventions it has ratified.

Companies that source leather and leather products from Pakistan should conduct thorough supply chain due diligence to ensure that the leather they buy is produced in a responsible manner. They should take action to prevent or mitigate the violation of workers’ human rights when and where these are taking place.

And what about you? You can help by sharing this story to raise awareness of the deplorable conditions for Pakistan’s leather workers.

Do you need more information?

-

Vincent Kiezebrink

Researcher

Partners

-

NOWCommunities

Related content

-

Hell-bent for leather Published on:

Vincent KiezebrinkPosted in category:Publication

Vincent KiezebrinkPosted in category:Publication Vincent Kiezebrink

Vincent Kiezebrink

-

The hidden human costs linked to global supply chains in ChinaPosted in category:News

The hidden human costs linked to global supply chains in ChinaPosted in category:News Joshua RosenzweigPublished on:

Joshua RosenzweigPublished on: -

Major brands sourcing from China lack public policies on responsible exitPosted in category:News

Major brands sourcing from China lack public policies on responsible exitPosted in category:News Joshua RosenzweigPublished on:

Joshua RosenzweigPublished on: