Will the G20 let private finance escape debt relief once again?

While the COVID-19 recovery is starting in various developed countries, many low- to middle-income developing countries are struggling with a huge debt overhang and low economic growth, which prevents them from financing COVID-19 measures, a recovery, climate mitigation or adaptation, and the UN’s sustainable development goals (SDGs).

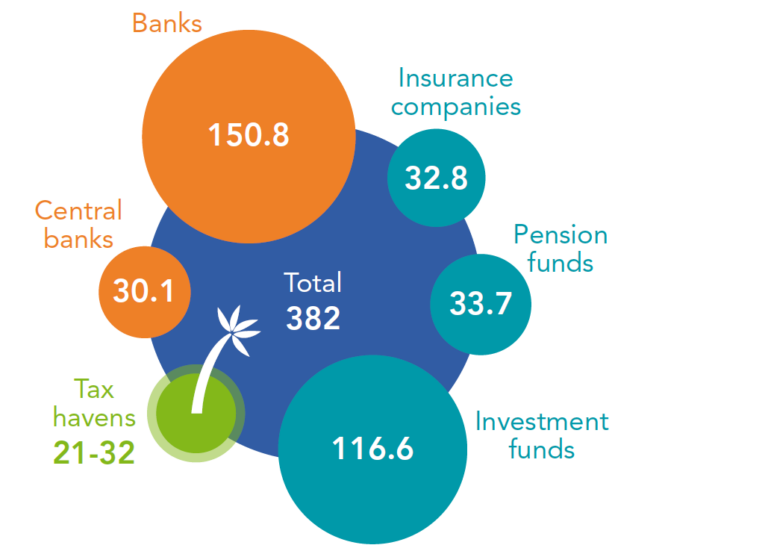

So far, there is not much clarity on how to resolve the emerging debt crises, since an international debt architecture to do so is missing. Any sense of urgency is absent from the 9 to 11 July meeting agenda of the G20 Ministers of Finance and Central Bank Governors, which will focus on an international tax agreement and climate finance. The G20 Debt Servicing Suspension Initiative (DSSI), which has been extended to the end of 2021, resulted only in the suspension of debt payments to bilateral public creditors by a few of the poorest countries. However, private creditors are now a growing part of the debt holders, especially in the form of . Private creditors, who are mainly based in rich G20 countries, did not suspend debt payments by DSSI countries, although the G20 officially ‘called upon’ them to do so(opens in new window) . Rather, the Institute of International Finance (IIF) set itself up as the spokesperson for the private creditors and responded with proposals that would avoid private financial losses and grow a profitable sustainable finance business, as explained below. Yet, the IIF cannot even claim to be a representative of all private creditors (see Figure 1 and see blog).

The IIF’s privileged access to the G20

The IIF has been working closely on the DSSI and debt issues with the G20 presidency in 2020. It sat in G20 meetings with officials and wrote extensive letters and documents, lobbying the G20 in various ways to clarify its position on how the debt issue should be handled.

The IIF(opens in new window) is a lobby organisation servicing 450 members from around the world, many of whom are large financial players in the debt market. They range from investment banks that issue bonds and provide complex loans (e.g. JP Morgan) to fund managers that buy developing-country bonds (e.g. BlackRock) and advisers for cases of debt non-repayment (e.g. Newstate Partners). The IIF’s 77 staff, US$ 35m budget(opens in new window) , 46 top executive board members, and members with high connections around the world have built a decades-long record of access to the highest official decision-making processes, including the G20. One standard way of influencing the G20 has been to organise IIF or B20 conferences just before important G20 finance meetings and invite Finance Ministers and Governors to give speeches an engage in dialogue on stage (and perhaps off stage as well).

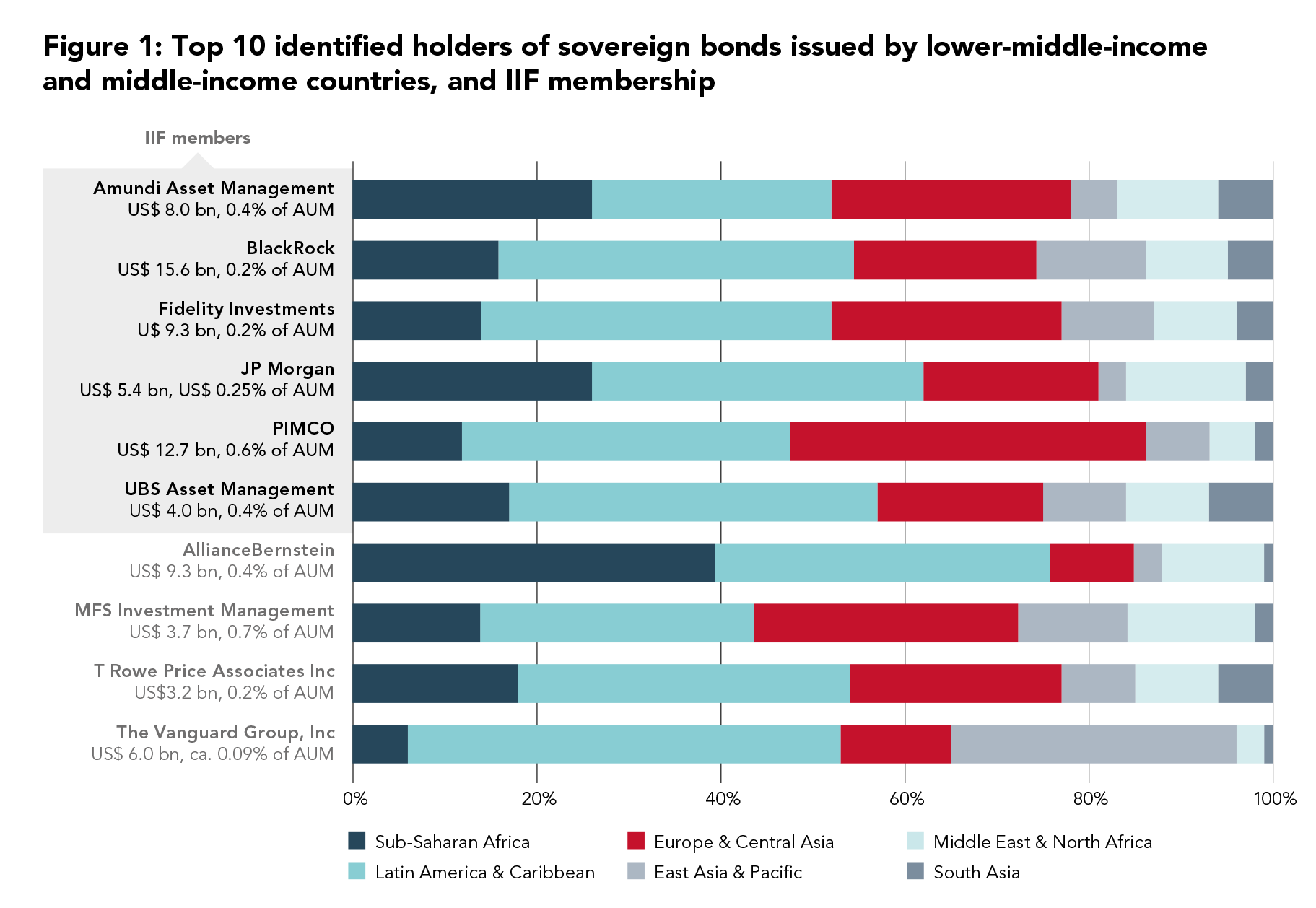

Analysing private bondholders of low- to middle-income countries exposes that IIF members are often not the majority of the bondholders (see blog). Of the top 10 bond holders of lower-middle-income and middle-income countries who that could be identified, only six were IIF members (see Figure 1). This casts doubt on the IIF’s presenting itself as being the spokesperson for all private creditors.

Sources: D. Munevar, Sleep now in the fire(opens in new window) , Eurodad, May 2021, p. 23-27: identification via database Refinitiv and percentage estimations AUM; https://www.iif.com/Membership/Our-Member-Institutions(opens in new window) (viewed 26 June 2021): identification of IIF members.

How private creditors escaped debt payment suspension

The IIF responded to the G20 DSSI with various documents and formats that would enable debtor countries to request debt payment suspension from the private sector. The IIF claims(opens in new window) that these documents were based on ‘robust discussions’ with IIF members and non-members as well as public creditors, who were given ‘candid feedback’.

An analysis of these IIF DSSI documents and formats(opens in new window) reveals that the proposed private creditor participation in the DSSI would be only voluntary and very complex. The IIF documents explained how low-income DSSI countries that request debt suspension would have to deal with difficult procedures due to contractual protection of private creditors and other legal obligations. Identifying the dispersed bond holders would not be easy. The countries would have to incur huge costs because they would have to hire a range of legal and financial advisers, pay extra interest, and even provide financial incentives to convince private creditors to come on board. This can barely be seen as an encouragement to DSSI countries to approach private debt holders for debt payment suspension or concrete support.

Most important, the IIF’s central argument in all its letters to the G20 and in DSSI documents has been to maintain ‘market access’. According to the IIF, it is ‘vital’ that DSSI countries continue to be able to raise private credit, e.g. issue bonds. This was in contrast with the DSSI requirement not to get commercial credit. In practice, access to private finance can be, and has been, reduced for DSSI countries that requested debt suspension, because credit rating agencies downgraded their credit rating (which makes private credit too expensive or a no-go). The IIF offered a ‘Template waiver(opens in new window) letter agreement for debtor countries participating in the G20/Paris Club DSSI’. However, the only thing this would help DSSI countries with is that they can request an exemption from being sanctioned by their lenders due to contractual clauses following a rating downgrade. In other words, although the three global credit rating agencies and their users are members of the IIF, the IIF did not deal with the downgrade problem.

The IIF’s written and verbal explanations of market complexities and unresolved problems, and especially the threat of losing access to private credit, resulted in most DSSI countries declining to ask for debt payment suspension. So far, no private creditor has provided debt payment suspension to a DSSI country. Moreover, the IIF warned the G20 to not impose ‘any coercive or top-down approach’ on private creditors. In a thinly veiled threat, it argued(opens in new window) that this would ‘undermine the functioning of the private financial markets, jeopardizing market access and capital flows well beyond those to DSSI-eligible countries’.

The consequence of the lack of private creditor participation in the DSSI, and the lack of debt relief initiatives for other developing countries, has been that developing countries have continued to service debt to private creditors, with . Since public creditors provided some debt relief and cheap loans, this public money has provided developing countries the financial space to pay back expensive private creditors. Some developing countries were able to continue accessing private financing, which further increased their debt burden.

IIF’s promotion of private sector interests at the G20

On 15 July 2020, the IIF warned that the worsening debt situation warranted not only debt payment suspension but also debt restructuring. In November 2020, the G20 issued a G20 for Debt Treatments beyond the DSSI, which would arrange debt relief for low-income countries. The Common Framework requires private creditors to provide debt relief on terms at least as favourable as those of official bilateral creditors (comparability of treatment principle). However, the IIF quickly responded that private creditors were ‘concerned’ about such comparable treatment. This response signalled that the IIF would potentially apply comparable debt treatment only on a case-by-case basis.

In order to influence the development of the details of the Common Framework, lengthy IIF letters have urged the G20 to include private sector creditors ‘before finalization of the key parameters’. The IIF argues(opens in new window) that ‘building a meaningful, regular public-private sector dialogue and consultation’ to develop the Common Framework would preserve developing countries’ access to private financial markets for continued and new private financing.

Such private financing would be ‘essential’ in filling the ‘massive financing gap for the 2030 UN SDGs – which for emerging markets alone is estimated at US $2.5tn annually’. The IIF argued that private money for SDGs would be widely available(opens in new window) and promotes it by collaborating with other (financial) industry bodies and law firms in order to scale up ‘global sustainable capital markets across asset classes – including equity finance, investment funds, green, blue and social bonds, SDG-linked and sustainability-linked instruments such as nature performance bonds, green loans, money market products, derivatives and insurance solutions’, as well as debt-for-nature swaps. The IIF suggested that this new – and profitable – private SDG and sustainable finance business could be supported by public de-risking, including ‘blended and credit-enhanced financing for sustainable infrastructure’.

More public financing might become available in the coming months when the IMF’s (SDRs) are being agreed upon and SDRs from developed countries are allocated to developing countries. Although the IIF notes that freed-up and SDR resources should be spent on responding to the COVID-19 crisis, with IMF programme conditionality, the disclosure of this spending by developing countries would provide confidence to private creditors and underpin ‘the overall goal of stable [private] capital flows’.

In such a scenario, public money would be spent on new private SDG/sustainable debt instruments, in addition to current debt servicing, rather than on debt relief. The lack of political will by the G20 to force the private sector to engage in debt restructuring, fuelled by the IIF’s arguments and private-sector protective bon and loan contracts, might lead to more public debt relief flowing to private creditors. Note that lower-middle-income and middle-income countries will have to pay US$ 330bn to (see Figure 1) between 2021 and 2025 (principal repayment and interest –‘coupon’– payments).

The IIF’s voluntary transparency initiative

Many institutions have pointed to the difficulty of identifying all debt holders, in particular private lenders and bondholders as well as Chinese private and public financial institutions. The IIF has also been insisting on debt transparency, since that provides private creditors and others with better insight into the risks they might face in the short or longer term.

To encourage public disclosure by private creditors, the IIF proposed the ‘Voluntary Principles for Debt Transparency(opens in new window) ’. However, analysis of the IIF website shows that while the IIF has excellent data on, and analysis of, the debt of emerging markets and other developing countries, it rarely makes those data publicly available. Rather, the ‘Voluntary Principles for Debt Transparency’ will be applied through creating an external repository where private creditors can deposit their debt data to be publicly disclosed. The OECD has taken up this task, which is called the ‘debt transparency initiative’ (DTI) and funded by the UK government (i.e. taxpayers’ money) and some private-sector donors.

The DTI is being developed with the same limitations as the IIF transparency principles: disclosure is fully voluntary, even not bound to IIF members, and consent of the borrowing country is needed. Moreover, disclosure applies only to loans and non-publicly traded debt securities (excluding traded bonds, which are mainly accessible via costly databases), and covers only low(er) income countries. This made civil society sound the alarm(opens in new window) , including over the OECD’s lack of expertise and the absence of debtor countries’ involvement. In their 7 April 2021 communiqué, the G20 Finance Ministers mentioned that they were looking forward to updates on the implementation of the IIF’s transparency principles. The G20 should seriously examine this flawed transparency initiative based on private principles before considering to endorse it.

The G20 should not endorse IIF private voluntary debt standards

The G20 endorsed the IIF’s Voluntary Principles for Debt Transparency (in 2019) as well as the IIF-sponsored ‘Principles on Stable Capital Flows and Fair Debt Restructuring’ (in 2004). In its letters and DSSI documents, the IIF refers to those principles as standards for debtor countries’ behaviour towards private creditors and for how debt problems should be treated.

The IIF on the implementation of the Principles on Stable Capital Flows and Fair Debt Restructuring. It services IIF members and non-members who are the Principles’ trustees and the Principles’ ‘consultative group’ and who regularly discuss what happens in debt-distressed developing countries. Note that the Principles’ trustees are chaired by the Governors of the central banks of France and China, who attend G20 finance meetings, and the IIF board chair, who also chairs the board of UBS, a major debt holder (see Figure 1).

The IIF recognises that the Principles on Stable Capital Flows and Fair Debt Restructuring were not up to the challenge of dealing with debt during the pandemic. It has therefore announced(opens in new window) that it will improve the Principles on seven issues, including how to deal with pandemics, comparable debt treatment, and integration of ESG considerations. The IIF has already announced it will seek renewed endorsement by the G20 of the Principles once this market- and industry-led initiative is updated. This is expected to occur later in 2021.

The question is why the G20 should endorse these Principles, which are voluntary even for IIF members, and provide no guarantee that the private sector will be willing to participate in debt relief, as the DSSI experience has shown.

The G20 is not up to the challenge to get debt relief from private creditors

In conclusion, the IIF’s proposals to deal with the debt of the poorest countries were ineffective, too costly, only short term and not even solving the private creditor transparency problem. The core argument to maintain market access does not hold any more in the current scenario in which developing countries’ capacity to borrow is close to being exhausted, as explained by the head of the bank of central banks(opens in new window) (the Bank for International Settlements, BIS).

Beyond the DSSI, the IIF’s proposals(opens in new window) to improve the restructuring process of ‘high and rising debt levels’ and prevent the increasing likelihood of a debt crisis include more private-sector debt-creating instruments, some of which would be subsidised with public money (blended finance, guarantees). In addition, ‘[debt] transparency, meaningful public-private sector dialogue, appropriate use of collective action clauses (CACs), and effective [public-private] creditor committees’ would be needed. This would encompass market-based so-called SDG solutions, including carbon-credit trading markets that would finance carbon-offset projects in the South.

The IIF does not mention that bondholders have enthusiastically taken the risk of buying developing-country bonds with low credit ratings but high interest rates, one example being the 31-year of US$ 1bn with a B rating and an interest rate of 8.95% (2019). to manage at least US$ 15.6bn in lower-middle-income and middle-income developing country bonds, representing 0.2% of its assets under management. BlackRock returned US $3.8bn to its shareholders after making a record profit in 2020. manages at least US$ 5.4 bn of such developing country bonds (ca. 0.25% of AUM) and will return an estimated US$ 38bn to its shareholders (in dividends and share buy-backs) based on 2020 profits. This shows that private creditors have plenty of leeway to provide debt relief and prevent future debt market turmoil, which could damage their bond-based business.

The IIF has thus been defending private creditors and asset managers who showed little willingness to assume the risk they took but continue to profit from high interest premiums. While many private creditors who have leeway to provide debt relief are based in the rich G20 countries, the G20 failed to take effective action that ensures that private creditors will swiftly provide debt relief, not only debt payment suspension, under the Common Framework and for middle-income countries. In this way, the G20 allows the debt problem to grow, become a source of financial-system instability and contribute to the risk of a financial or economic crisis.

The G20 Central Bank Governors should recognise that investors’ risk-taking was facilitated by their monetary policies (QE and low interest rates), in a regime of free capital flows with treaty and IMF restrictions on capital controls. The G20 has the responsibility to avoid negative impacts of changes in monetary policies on developing countries, such as capital outflows and currency devaluations, which make debt repayment more expensive.

The G20 should not be side-tracked by IIF arguments for market-based solutions that lead to more debt to be repaid to private creditors. Instead, it should focus on how debt relief and cancellation by private creditors can be organised, for instance by stress-testing those credits and allowing them to be written off in an orderly way. Also, the US and the UK should be willing to change bond contract laws which binds many developing countries and make bond holding more transparent. To provide a structural long-term solution, as opposed to a costly, protracted case-by-case treatment as advocated by the IIF, the G20 should signal its support for negotiating a global debt architecture reform to start at the UN, which would bring all developing countries to the table. The purpose of all debt relief and reform should be that developing countries can channel money away from debt-servicing payments into servicing their citizens in an equitable and sustainable manner.

SOMO will soon publish a more extensive study on this subject.

Do you need more information?

-

Myriam Vander Stichele

Senior Researcher

Related content

-

Growing investment in developing country bonds problematic for financial stabilityPosted in category:News

Growing investment in developing country bonds problematic for financial stabilityPosted in category:News Myriam Vander StichelePublished on:

Myriam Vander StichelePublished on: -

Myriam Vander StichelePosted in category:Publication

Myriam Vander StichelePosted in category:Publication Myriam Vander Stichele

Myriam Vander Stichele

-

Which threats are lurking in the financial sector? Published on:

Myriam Vander StichelePosted in category:Publication

Myriam Vander StichelePosted in category:Publication Myriam Vander Stichele

Myriam Vander Stichele